Pokémon Go: The app that tricks us into entering the real world

From all the headlines lately, you might assume the big news of the year is the long-awaited arrival of decent virtual reality (you know — Oculus Rift and other heavy, sweaty gamer headsets for game playing).

Actually, though, the bigger news may be augmented reality.

That, anyway, is the lesson of Pokémon Go, the free game for iPhone or Android phones. In its first week, this app has become the No. 1 most downloaded app, driven Nintendo stock up 34% (the highest since 1983), consumed Twitter, and driven millions of people into a Pokémon obsession.

In augmented reality (AR) apps, your phone is a lens for the world around you; the app superimposes text or graphics over the live picture. One AR app (New York Nearest Subway), for example, shows which subways are under your feet in New York …

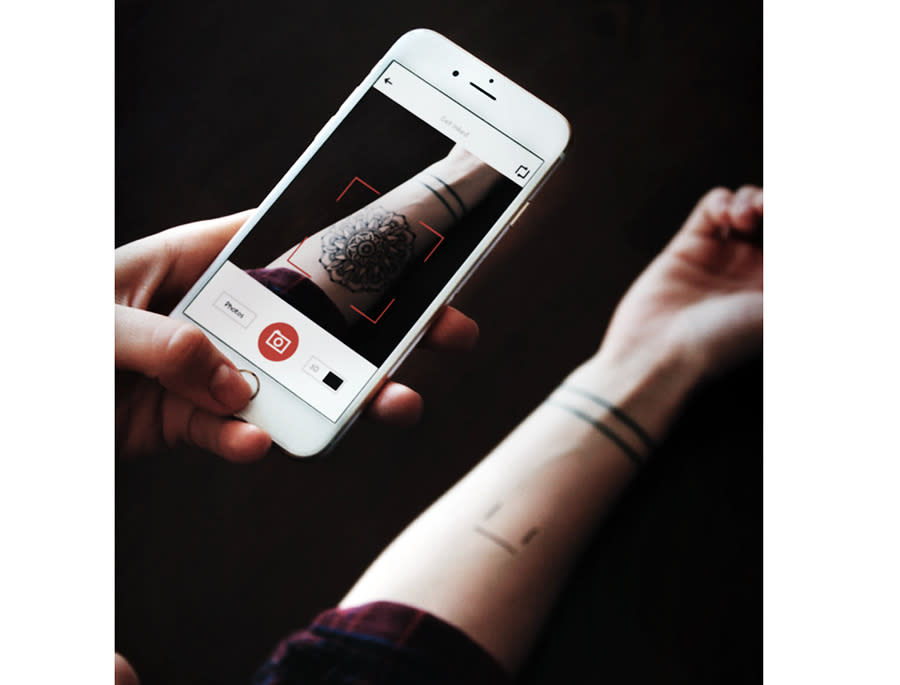

Another (Inkhunter) shows what a tattoo will look like once it’s on you:

Yet another app (Google Translate) converts foreign-language signs and menus into your language in the live video:

Pokémon Go Basics

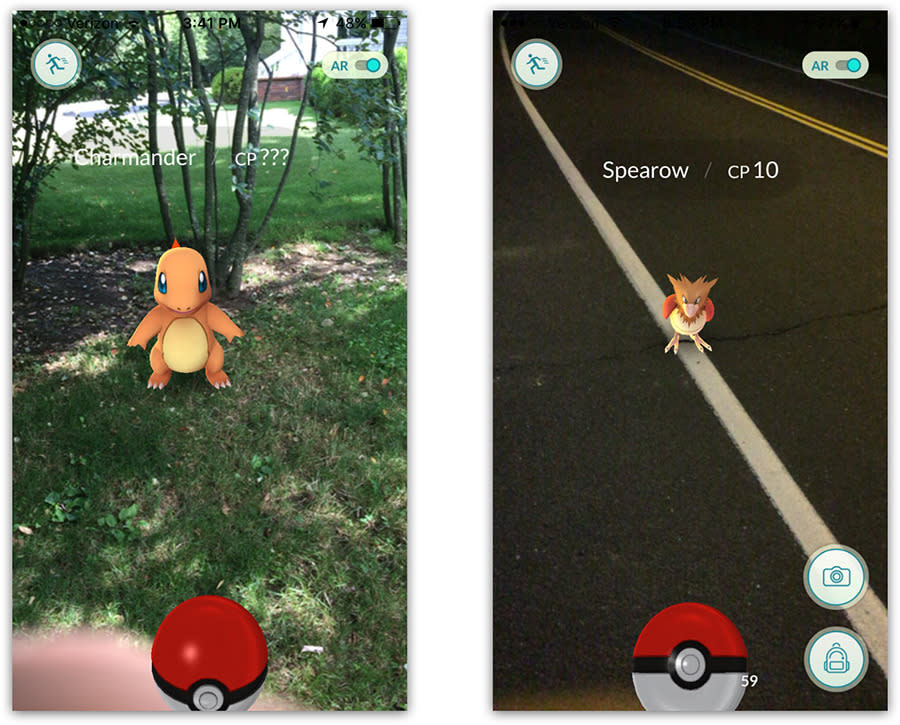

What Pokémon Go does, though, is to display Pokémon characters — cute little cartoon spinoffs of real-world animals, fish, birds, and bugs — in the physical world around you. (Yes, these are the same creatures that populated the classic Game Boy game, trading cards, movies TV shows, and young teenagers’ minds in the early ‘90s, but no familiarity is necessary.)

The object of the game is to capture as many of these beasts as you can. You use your phone as a viewer into their invisible world, and walk toward the critters as they’re revealed on the screen. Near water, you’ll find the fishier species; at night, they tend to be ghostlier; in parks, you find more bugs and birds.

(The game relies on Google Maps for its understanding of the world’s geography, parks, buildings, and so on — not a surprise, considering that its creator, Niantic, began as a Google company.)

You can collect more fuel for this quest — various toy-like gadgets to attract and capture more critters — by visiting real-world, public spots like museums, churches, plaques, fountains, and statues. Or you can buy them with actual dollars.

The main thing —the punch line, the headline, the bottom line — is this: You can’t play this game sitting. You have to get outside and walk.

A Deliberate Manipulation

John Hanke, who leads Niantic, fully admits that his purpose was to get today’s sedentary game players off their couches and into the physical world. He wants them to move more, to look at familiar neighborhood spots in a new way. And it works: This free, joyous game is manipulating millions into taking long walks and exploring their worlds.

There isn’t much interaction with other players while you’re playing the game; as I went critter hunting side-by-side with my wife, my phone had no knowledge of the fellow player two feet away. At higher levels, you can sic your most powerful Pokémon creatures against other people’s in places called Pokémon Gyms, but even then, you don’t really see or get to know your human co-hunters.

But there is a social aspect, in that playing this game is much more fun when you’re not alone. This past weekend, you could see couples or groups of pals out in the sunny summer world, waving their phones and exclaiming about rare creatures they’ve just nabbed.

Yes, of course, you’re looking at your phone the whole time; the Charmander that’s bopping around under that big oak tree — as revealed by your phone —doesn’t exist in real life.

But in the big picture, never mind. This game has children leaving the house to explore the neighborhood, shouting and running, for whole afternoons, in a way they haven’t since the 1970s.

In general, you can’t cheat the game by driving to find the next critter; at car speed, the game cleverly makes all the Pokémon (Pokémen?) disappear. It’s clearly the most fun when you’re on foot.

There’s more to it than just capturing adorable, quirky animals, of course. There’s a whole game, with bizarre rules borrowed from the original Pokémon game. You’re supposed to make your critters evolve by accumulating candy and stardust, or something. You can trade them back to the Professor for more candy. And, of course, there are those Pokémon Gym battles.

But all of that is an elaborate manipulation. It’s all meant to get us outside, to get us walking, to get us together. And, obviously, it works.

The app-hype cycle

There will be copycat games by the end of the month — probably by the end of this sentence. There will be a cooling period, where the novelty and the popularity wear off. (It will probably coincide with the country’s cooling period, known as fall and winter.) There will be more overblown stories about the dangers of Pokémon Go mania, like strangers trespassing on lawns or people discovering dead bodies on their neighborhood Pokémon quests.

There will be plenty of complaints about the frequency of the game’s freeze-ups, which often result from the company’s overloaded servers. And there will be legitimate gripes that Pokémon Stops and Gyms are common in cities, but hard to find in rural areas.

But guess what? All of that is part of the traditional pattern for anything that’s new, fresh and crazily popular. None of it should take away from the tremendous news that augmented reality, at long last, may get the recognition it deserves … that there truly is something new under the sun … and that a phone game, that bane of today’s overweight youth, is now getting them off the couch and into the fresh air and sunshine.

Don’t be surprised if you overhear a new phrase this summer, for the first time in the history of parenting: “All right, kids, put those books down. Time to spend some time with your electronics!”

David Pogue is the founder of Yahoo Tech; here’s how to get his columns by email. On the Web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. He welcomes non-toxic comments in the Comments below.