One of the Closest Stars Looks Friendly for Life

Finding a habitable planet in the nearest star system is an ongoing quest. But the overall habitability of the Alpha Centauri system based on its three stars, just over 4 light-years away, could be murkier than thought in some respects, and much brighter in others.

It all boils down to stellar weather. Tom Ayres, a senior research fellow at the Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy at the University of Colorado at Boulder, presented his findings on the radiation coming from each of the three Alpha Centauri stars at the 232nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

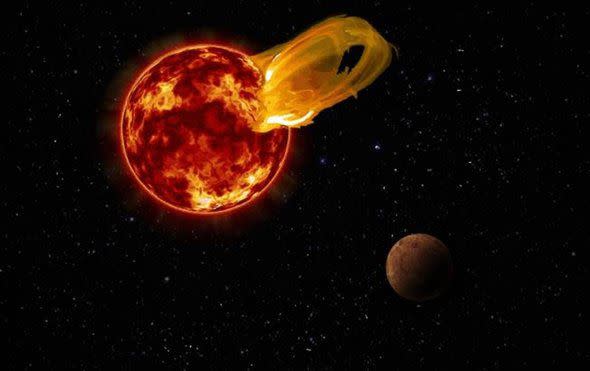

His research provides more evidence that Proxima Centauri (sometimes called Alpha Centauri C), is likely far too active for any orbiting planets to be habitable. Using the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, Ayres and his colleagues determined that Proxima is 500 times more active in X-ray radiation than the sun and has 50,000 times more large-scale flares.

That's a problem for the only confirmed planet in the entire Alpha Centauri system, Proxima Centauri b, which is a little more massive than Earth and technically within the habitable zone (in this case, very close to a small cold star). Stellar flares can strip off atmospheres, and Proxima b is so close to its star that the effect would be especially devastating.

"It would be an absolutely miserable place to be," Ayres said at the AAS meeting.

But the other two stars, Alpha Centauri A and B, appear to be potentially friendly to life-bearing planets... within limits. While Proxima Centauri is only a fraction of the size of the sun, Alpha Centauri A is slightly bigger, and B is slightly smaller. By carefully watching activity from the stars, Ayres and his colleagues determined that Alpha Centauri A has far less X-ray activity overall than the sun, meaning that by one metric, it would be friendlier to a life-bearing planet in the right spot than our own star. Alpha Centauri A also has slower flare cycles overall.

But Alpha Centauri B emits five to six times more X-rays than the sun, which could complicate the picture of life there, but not rule it out entirely. "We know in our own solar system the planet Mars was thought at the beginning to have a pretty substantial atmosphere," Ayres says, adding that the atmosphere seems to have been stripped away during a peak in solar activity.

At Alpha Centauri, any planets around A or B would be affected to some extent by both stars. "The space weather conditions there might be enough to remove the atmosphere of a planet like Mars," Ayres says.

However, during the uptick in activity from our sun-believed to be 10 to 15 times more active in X-ray radiation than it is now-Earth was spared. Venus and Mars, two planets nominally in the habitable zone, became too hot or too cold, with an atmosphere too thick or too thin to sustain liquid water. In the right conditions, perhaps a planet like Earth could withstand the radiation near the primary Alpha Centauri stars.

Where Are the Exoplanets?

Of course there is a problem: no known planets orbit either of the two big stars in the Alpha Centauri system. Even though they are so close to us, searching for exoplanets has proven incredibly difficult.

While Proxima Centauri is one-tenth a light-year away from A and B, A and B are very close to each other and very bright, which makes it hard to look for dips in light when planets transit in front. To make things harder, the two stars' equators aren't quite aligned to our field of view.

Another method currently used to find exoplanets, called radial velocity, relies on measuring how much an object's gravity tugs on its home star. But A and B get about as close to each other as 11 times the distance between Earth and the sun, or closer than the sun and Uranus, meaning they already have a very pronounced gravitational effect on each other.

"You have two very bright stars that are very close together, and that’s going to be the case for many years to come," Ayres says.

That leaves a method that's hard, but not impossible: try to capture a picture of a planet directly. Project Blue aims to do just this by using a small space telescope to try to find and take a picture of an exoplanet in the Alpha Centauri system. With a one-or-two pixel resolution of a planet there, it would be just enough to see a bit of color-and if it's blue, it might have water.

If we ever find a planet around the two primary stars of Alpha Centauri, it would be a unique world affected by not one but two large suns, and there would be a lot more questions before we could truely call it habitable or not.

You Might Also Like