The A1000 Is Disney's Advanced Animatronic Bringing Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge to Life

Glendale, California, isn’t exactly in a galaxy far, far away, but it’s here inside a beige building where Star Wars characters are brought to life.

Within its nondescript walls, safe from the unseasonably chilly February day swirling outside, all eyes are on Hondo Ohnaka, a scheming pirate from Star Wars: Rebels. His head bobs up and down, shaking his long green alien braids. His foot appears to step forward, rattling his bronze belt. His mouth curls into a wide smile before devolving into a deep belly laugh.

For a split second, it seems that this colorful horns-for-a-beard alien is flesh and blood. But Hondo is actually a Disney audio-animatronic, one of the most advanced ever built, and he’s getting ready for his debut at Walt Disney World’s Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge. He’s performing what’s known as “cycling,” going through his predetermined movements for 120 hours before installation at one of Disney’s theme parks.

“We work years to see this moment,” says Kathryn Yancey, Walt Disney Imagineering show mechanical engineer. “He’s been on the computer for so long, when he’s right there in front of you…it’s amazing.”

In December 2015, Yancey and others began visualizing, conceptualizing, and constructing Hondo. Three years later, it’s no wonder why emotions are high. “He moves, he talks, and has a personality,” says Yancey. “Hondo is real to us.”

Hondo represents 55 years of animatronic evolution, beginning with pneumatic-controlled birds, graduating to hydraulic-powered former presidents then innovating to electrified wicked witches. But Hondo is an evolution beyond anything Disney has ever attempted, and offers a moving, talking glimpse into Disney’s newest, largest, and most ambitious attraction.

The A1: Singing Birds and American Presidents

Disney’s Grand Central Creative Campus in Glendale (known to insiders as “GC3”) is home to Walt Disney Imagineering’s full-service animated figure workshop. This is where Imagineers conceptualize, plan, build, engineer, program, paint, costume, and test audio-animatronic figures that will end up in one of Disney’s 12 theme parks across the globe.

Everything from beginning to end happens in this building. Some of Disney’s most closely guarded secrets live here, so access to outsiders is restricted. But as Galaxy’s Edge nears its opening day this year, Popular Mechanics was granted a rare exception.

The first audio-animatronic, defined as a robot that pairs movement and audio, debuted in Disneyland in June 1963. While on vacation in New Orleans, legend has it that Walt Disney bought a caged mechanical bird and had Imagineer Wathel Rogers take it apart to see how it worked. The bird became the inspiration for the singing macaws at the Enchanted Tiki Room.

When the attraction opened, Disney said engineers used a “new type of valves and controls developed for rockets,” referring to pneumatics and compressed air rockets, to create automated movements in his robot birds. They also used a magnetic tape system called the Digital Animation Control System (DACS), originally invented for nuclear weapon launch machinery, to synchronize the movements with audio and music.

A year later, Disney built its first human audio-animatronic: the more advanced mostly hydraulic President Abraham Lincoln. Developed for the 1964 World’s Fair, the president was animated by pneumatic actuators and was sculpted using Leonard Volk’s 1860 life mask (they also used dentures and glass eyes procured from a local mortician). The result was a lifelike Lincoln, which still gives history lessons to visitors at Disneyland to this day.

And this past is still very visible here at Disney’s animated figure workshop. Mounted on a wall is the lid of the crate that shipped Mr. Lincoln to the World’s Fair. Below that is one of the original macaws from the Enchanted Tiki Room. Together, they illustrate a huge leap forward for audio-animatronics.

“[Pneumatic] allows traveling from one end to the other, but can’t really control or hang out in between that range,” explains Walt Disney Imagineering associate Disney show mechanical engineer Victoria Thomas. “Hydraulics allow going anywhere within the range and changing direction.” Yancey adds that there’s more control in hydraulic figures, which “gives the illusion of fluid motion.”

In 1969, with construction on Florida’s Disney World commencing, development began on the next evolution of the audio-animatronic: a strictly hydraulic non-character-specific tool kit that allowed for standardized, adjustable, and efficient builds out of the dozens of animatronics that would be needed for the new park. This became known as the A1 figure.

These figures were built, customized, and installed in what are now iconic attractions like Pirates of the Caribbean and Haunted Mansion. While today many of those original A1 audio-animatronics have been refurbished with more advanced machinery, there are still a few left in both U.S. parks. At Disneyland, a number of the pirates in the background are still A1s. In Orlando, in the Hall of Presidents, former commander-in-chiefs like Rutherford B. Hayes or William Henry Harrison, who just stand there and nod, are also A1s.

But A1 figures are heavy, bulky, and hard to adjust. So to fit all of these components, the animatronics need to be slightly larger, or as Thomas puts it, “a tall and a little bit beefy standard human.” They are also limited in functions, which is defined by points of articulation of a given figure that bends on one axis.

“An elbow movement is a function,” says Thomas. “Your wrist twist, that’s a function.”

A typical A1 figure was a fully functional generic humanoid but the number of functions was dependent on what version of head was installed.

It wasn’t as complex as C-3PO, but it was a start.

The A100: Wicked Witches and Boisterous Pirates

By the mid-1980s, Disney knew they needed to upgrade. A new software setting was developed termed “Compliance,” which alleviated the pressure on the entire body during a single movement by acting as a shock absorber. A combination of this software, customized hydraulic values, and hydraulic actuators took the so-called “shake” out of the figure.

“A typical robot is harsh in movements. Softening that is an art,” says Yancey. “In order to smooth the animation curves, you have to manipulate the acceleration and velocity curves to create that fluid, human-like [movement].”

Function stacking order was also improved, meaning how, when, and in what order different joints move. “Each function has an affect on each other,” says Yancey. “Your arm is affected by wrist functions. A shoulder is affected by a head function. It’s a domino effect.”

But simple things like day-to-day maintenance also needed improvements. With more audio-animatronics, Disney needed better ways to keep them all running. Soon parts became replaceable and engineers limited movements so certain actions only wore on replaceable joints. This made it possible for the audio-animatronics to be easily maintained for years.

The A100 debuted in 1989 in the form of the Wicked Witch of the West in The Great Movie Ride at Orlando’s Disney-MGM Studios (now Disney’s Hollywood Studios). While the attraction has since shuttered, her movements and evil cackling were creepily lifelike.

“When [the A100] was first released,” says Thomas, “it had the most dynamic lifelike performance side of anything we've ever made.”

Like the A1, the A100 is really a tool kit allowing engineers and builders to use certain components as needed, and there are still plenty of fully functional A100 in the parks today. Many of the Jack Sparrows in the Pirates of Caribbean rides are A100s. As well as George Washington and Abe Lincoln in Orlando’s Hall of Presidents-so is Donald Trump.

Since 1989, the A100 has been adapted to meet changing needs and technologies. Electric became preferred over hydraulic mainly because it provides even more control over functions and the actuators don’t degrade as much over time. A good example of a highly advanced electric animatronic is the shaman in Na’Vi River Journey at Animal Kingdom in Orlando, a beta prototype of which sits a few feet away from us as we talk.

“She has the most functionality of any figure we’ve ever made,” says Thomas. “And she’s only from the waist up.”

The one drawback of electric is that it requires a good deal of internal structures, cables, and motors. The concept of “packaging” comes into play, meaning how a figure is costumed or built to hide all the necessary components they need. So smaller characters, like Elsa in the Frozen Ever After ride at Epcot, can be particularly challenging. But tough tasks breed creative solutions.

“The whole attraction is scaled,” says Thomas, “so that Elsa…looks proportionate but still large enough to fit mechanical design that was robust and maintainable.”

The A1000: A Galaxy Far, Far Away

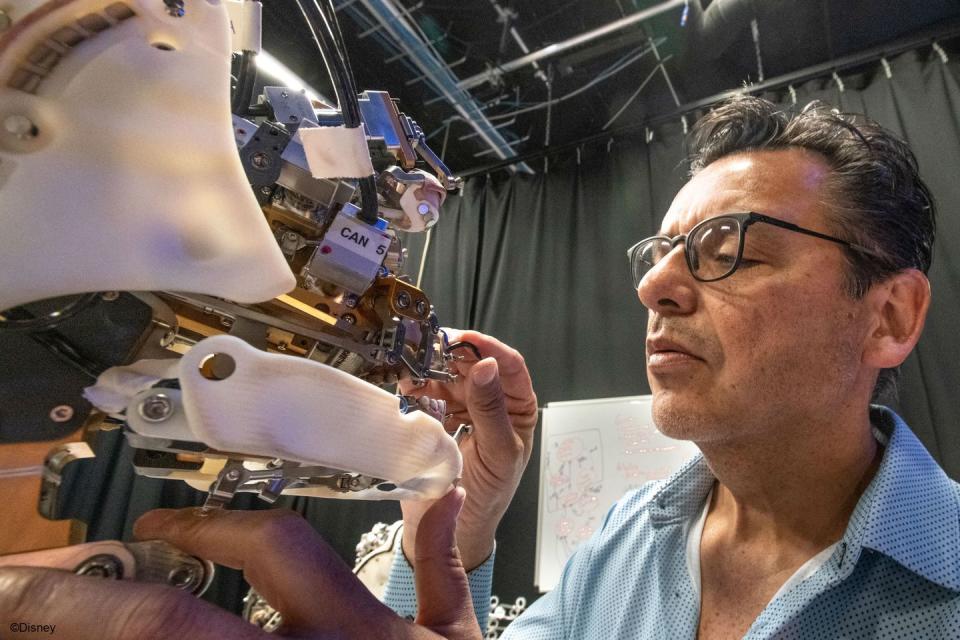

Work on the next evolutionary step in audio-animatronics-the A1000-was already in motion (so to speak) before the 2015 Star Wars attraction announcement. Yancey and Thomas say their team were working on eight different sizes of A1000 for about a year before being asked to take what they learned and apply it to creating customized Star Wars figures. It was perfect timing.

The goal of the A1000 program was to create a family of standardized electric figures that provides more control and design repeatability for both build and maintenance purposes. So Disney pioneered proprietary software programs that provide predictive renderings and pre-visualizations that assist in everything from seeing how a figure moves in a costume to predicting when components need replacing. But the ultimate goal is to get as close a lifelike performance as possible.

“You’ll talk to animators who have mirrors at their desks and watch themselves move,” laughs Yancey. “We use each other as inspiration.”

Enter: Hondo Ohnaka. When installed as part of the attraction Millennium Falcon: Smuggler’s Run, Hondo will be one of the most advanced audio-animatronics at any Disney Park. He has 51 total functions, including ten in his head alone-a big evolution from its A1 ancestor.

He also has a speaker in his chest to provide directional sound (first done with Rocket Raccoon in Disneyland’s Guardians of the Galaxy attraction), and there’s a bend in his knee, creating the illusion that Hondo can walk. Imagineers in California worked alongside engineers and designers in Florida to develop these new A1000 figures.

With skin made of a lifelike silicone mix, Hondo’s voice and movements look as real as the Imagineers watching him. “You [see] his beautiful face,” says Yancey. “He’s such an amazing and dynamic character.”

While Hondo won’t be the only A1000 at Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, Disney is keeping quiet about what other favorite Star Wars characters will be coming to life. But for the first time since Lucas’ original captivated the world 40 years ago, Star Wars has never felt so real.

“If [the audio-animatronics] are physically in front of you, you’re in their story,” says Yancey, “and they are in yours.”

('You Might Also Like',)