I lost my voice because of a tumor — but an AI clone gave it and my confidence back to me

A woman lost her voice — but artificial intelligence helped her get it back.

Alexis “Lexi” Bogan had a golf ball-sized vascular tumor lodged near the back of her brain, pressing on her brain stem and entangled in blood vessels and cranial nerves.

Doctors removed the life-threatening tumor during a 10-hour surgery in August 2023; however, when Bogan came off the breathing tube, her tongue muscles and vocal cords were damaged.

It affected her ability to eat and talk — she struggled to swallow and could barely choke out a “hi” to her parents.

But AI came to the rescue months later.

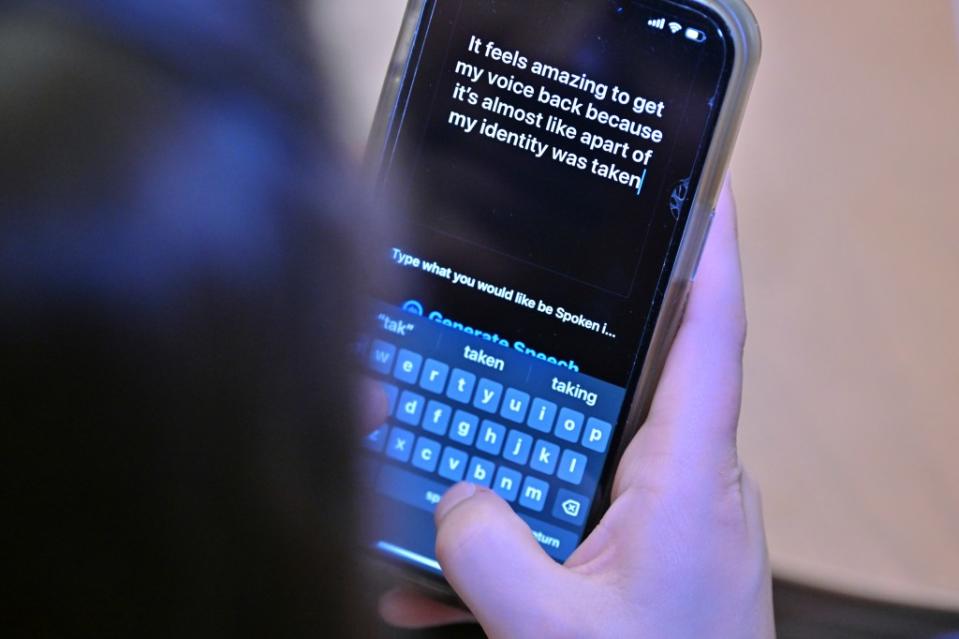

In April, Bogan got an AI-generated voice clone that she can use through an app on her phone — she just types into her cell, and the app instantly reads her words out loud.

Before the vocal miracle, even after months of rehabilitation, the 21-year-old was still struggling to speak and get her loved ones to understand what she was saying.

“It’s almost like a part of my identity was taken when I lost my voice,” Bogan told the Associated Press. “At some point, I was starting to forget what I sounded like.”

Her new app-based voice, with help from Rhode Island’s Lifespan hospital group, is sourced from a 15-second cooking video she recorded for a high school project, allowing it to use her teenage vocals for a real-sounding voice.

“I get so emotional every time I hear her voice,” her tearful mother Pamela said.

Bogan is one of the first people to use OpenAI’s new Voice Engine to bring back a lost voice — and the doctors believe that this is one use of AI that outweighs the risks.

“We’re hoping Lexi’s a trailblazer as the technology develops,” Dr. Rohaid Ali, a neurosurgery resident at Brown University’s medical school and Rhode Island Hospital, told AP, adding that it could greatly benefit those with debilitating strokes, throat cancer or neurogenerative diseases.

Bogan now uses the app everywhere, including Starbucks, Target and Marshalls, to help with every day encounters.

“I think it’s awesome that I can have that sound again,” said Bogan, who noted that it helped “boost my confidence to somewhat where it was before all this happened.”

Some risks of AI voice-cloning technology include non-consensual voice recreation — making people say things they never said — plus phone scams, deepfake robocalls and more.

“We should be conscious of the risks, but we can’t forget about the patient and the social good,” said Dr. Fatima Mirza, another resident working on the pilot. “We’re able to help give Lexi back her true voice and she’s able to speak in terms that are the most true to herself.”

Since Bogan is the first with her condition to use the technology, she’s been able to give feedback on how to make it better and more accessible, such as having the voice age as she ages.

“She’s been a great inspiration for us,” Mirza said.

“Even though I don’t have my voice fully back, I have something that helps me find my voice again,” Bogan said.