Get terrorism off the Internet? It’s (still) not so simple

Since this week’s mass murder in Brussels — yet another terrorist attack launched by locals, not foreigners — people have again been asking a simple question: Why do we allow the authors of such atrocities to keep recruiting people online?

The most public and extreme expression of that came in December, when Republican frontrunner Donald Trump said he’d support “closing the Internet up in some way” to shut out terrorist groups like the Daesh death-cult that pretends it’s an “Islamic State.”

Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders recognize that you can’t actually build a wall in the Internet. But after Brussels, they too called out the importance of stopping terrorist recruitment online.

Social networks aren’t just sitting around

It’s not as if the major U.S. social networks have been idle. In February, Twitter announced on its own blog that it had “suspended over 125,000 accounts for threatening or promoting terrorist acts, primarily related to ISIS.”

That post went on to explain that the company had increased its staff devoted to the issue and had begun combining reviews of suspicious accounts with automated scrutiny to find others like them.

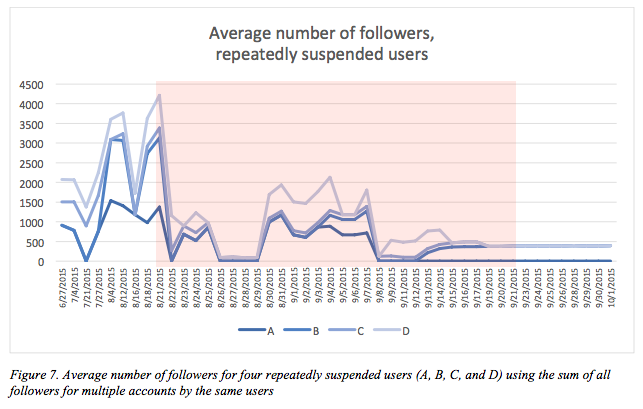

Has that made a difference? A February study published by George Washington University’s Program on Extremism found that this campaign was not a futile Whack-A-Mole game; as Daesh/ISIS supporters came back online with new accounts, they found fewer followers.

Graph from “The Islamic State’s Diminishing Returns on Twitter: How suspensions are limiting the social networks of English-speaking ISIS supporters,” by J.M. Berger and Heather Perez

Facebook, in turn, has tightened its community standards to ban even condoning terrorism, and now has five offices around the world devoted to monitoring and taking down terrorist content.

At a panel discussion yesterday on the responsibilities of tech companies vis a vis terrorists, the Software & Information Industry Association’s public-policy vice president, Mark MacCarthy, commended the “zero tolerance” rules at Twitter and Facebook for terrorist recruitment. “These policies are proving to be reasonably effective,” he said.

Another panel member, Google public-policy counsel Alexandria Walden, said that company’s YouTube service takes action on 100,000 videos a day that violate its community standards.

Beyond the fact that blocking access from an entire country as Trump has called for is nearly impossible if you don’t occupy it first (and it’s still not easy afterwards), State Department special advisor Jason Pielemeier observed that such a move would risk cutting off some of our own intelligence sources: “It might also block human rights activists who are trying to document atrocities.”

He added: “There are parts of the government that are very concerned about taking this stuff off the Internet where it’s visible and can be tracked.”

Filtering out the the filth of Daesh propaganda automatically would be even harder, and in some cases could lead to evidence of atrocities going unseen.

This sort of screening and erasure of content would violate the First Amendment if the government ordered it. But Twitter, Facebook, and Google’s platforms are private spaces, and they get to set the rules for who gets to post things there for free.

The problem of ‘counterspeech‘

The second half of this discussion often goes something like this: How can America, the superpower of advertising and marketing, win this battle of ideas?

Early attempts at such countermessaging have gone over as well as most government propaganda (which is to say not very well at all). More recently, Washington has been seeking the help of private industry in Silicon Valley, Hollywood and Madison Avenue. But effective marketing requires knowing your target market.

At Wednesday’s panel, Emma Llansó, who runs the Center for Democracy and Technology’s Free Expression Project, said she doubted that any such “Madison Valleywood Project” would look “very authentic or credible.”

The most effective “counterspeech” is likely to come from people with similar backgrounds as the targets of radicalization efforts — say, an imam who doesn’t subscribe to Daesh’s abhorrent distortion of Islam. But keeping people off the Internet because they tweet from a certain area or about certain topics risks silencing those positive contributions.

(Remember that most of Daesh’s victims are themselves Muslim. Over this month, Daesh-linked attacks in Ankara and Istanbul killed more people than in Brussels.)

A more recent government program, as outlined in a Daily Beast post by Kimberly Dozier, would identify those authentic voices and channel technical help and funding towards them. That might work better — as long as the intended audience doesn’t then see those counterspeakers as U.S. puppets.

The Internet isn’t really the issue anyway

As a deeper read of coverage about the Brussels atrocities should make clear, our bigger problem remains not piecing together clues that were already in hand. It’s starting to look like Belgian investigators didn’t follow up on leads they had, just as French police missed hints about the Paris attacks, and U.S. authorities did the same with clues prior to the 9/11 attacks.

And yes, it does not help our cause when political candidates who probably couldn’t name the five pillars of the Islamic faith announce that Muslims represent a collective risk. No discussion of radicalization can ignore that factor.

But there’s a rich history of politicians suggesting the Internet and the tools we use on it represent a primary explanation for real-world problems — see, for instance, blaming encrypted phones and communication for making the Paris and San Bernardino attacks possible. We invented all this stuff, the arguments go; why can’t we just tell the nerds to think harder, flip the right switches and make the issue go away?

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.