Facebook’s Vision for the Future: Drones With Lasers, All-Seeing AI, VR for Real

Photos by Rob Pegoraro/Yahoo Tech

DUBLIN — The satellite is the simple part of Facebook’s technological vision for its next 10 years. After that? It’s complicated.

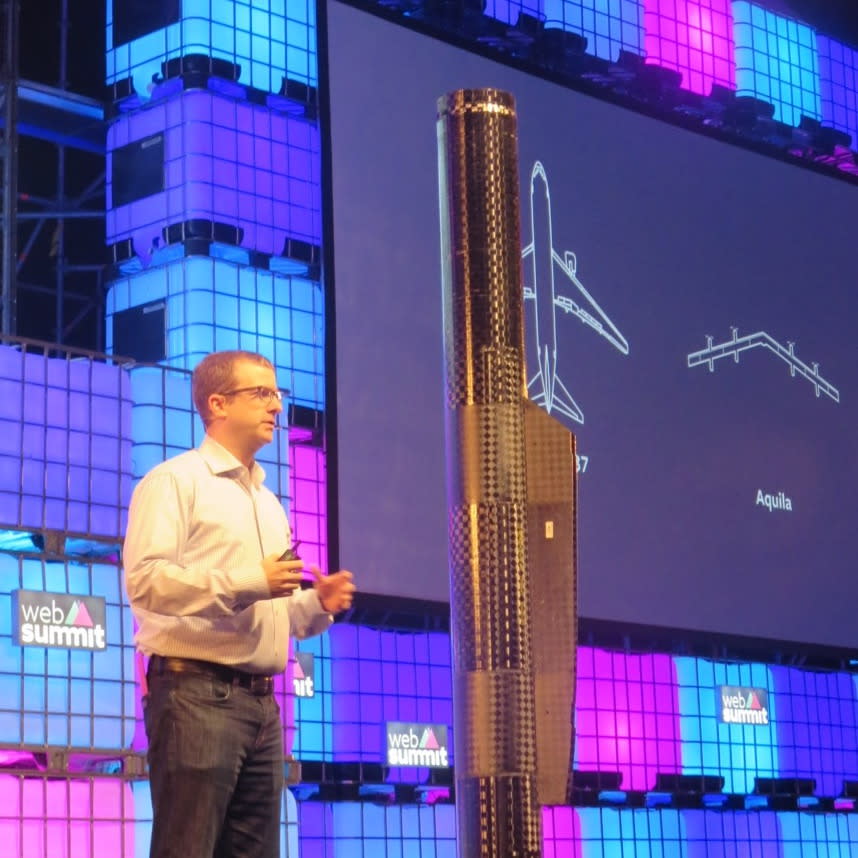

In a talk Tuesday morning at the Web Summit here, Facebook chief technology officer Mike Schroepfer gave a quick overview of the social network’s efforts on three tech frontiers: bringing Internet access to the rest of the world; teaching machines to “see” the present and predict the future; and making virtual reality an everyday, hands-on reality.

Droning on

The first problem is the hardest: Even if you count slow 2G wireless connections, 2.5 billion people across large swaths of the world have no Internet connectivity, Schroepfer said. Facebook would like to change that — and, presumably, earn some Likes from the newly connected. But traditional wired and mobile service can’t cover those distances.

(Facebook already subsidizes free mobile access in developing countries to itself and other popular sites. Schroepfer didn’t get into that, nor did he address complaints about what this “Free Basics” program does to sites left out.)

Satellites can be a solution for some low-density areas, which is why Facebook plans to launch one next year in partnership with the French firm Eutelsat. But for most of these offline areas, Schroepfer said, “We think you need to go to the sky.”

Facebook’s intended solution is a flock of solar-powered, propeller-driven drones that would fly circles at 60,000 to 90,000 feet up for three months at a time, storing electricity in lithium-ion batteries during the day. They would pick up Internet access from the nearest spot on the ground with sufficient connectivity, then bounce that signal from drone to drone via laser or radio-frequency links.

Getting something with the wingspan of a Boeing 737 to fly on sunlight is not easy. (Google is opting for a balloon-borne system, which has its own problems, including navigation and leaks.) Schroepfer said a big part of Facebook’s solution is making this carbon-fiber plane as light as possible — only 800 to 900 pounds. He demonstrated that lightness onstage by easily hoisting one of its engine nacelles — a tube maybe 15 feet long.

For this scheme to work, Facebook also needs laser signals that could reliably convey data over gaps as long as 11 miles “We’ve done systems in the labs that give us 10s of gigabits,” Schroepfer said. But the real tests won’t happen until the first flight of a prototype drone — named Aquila, Latin for eagle — which he said Facebook hopes to have happen “very, very soon.”

Visions of machine vision

The next problem Schroepfer discussed should be familiar to anybody who feels swamped by his or her News Feed: information overload. Rather than getting us to unfriend those pals who refuse to ever shut up, Facebook is working on artificial-intelligence software to manage the growing glut of data, on and off the social network.

For example, he showed how one routine can answer complex questions about the plot of The Lord of the Rings after being presented with a basic summary of its plot.

“We want to do the very best job we can of showing you exactly what you want in your feed,” Schroepfer said. This effort will flow into the “M” personal-assistant service, which some Facebook users can ping for help from within the Messenger app.

Facebook is also working on machine vision: not just recognizing the different subjects in a photo, but being able to answer plain-English questions about them. Schroepfer shared a scenario in which someone with impaired vision is presented with a photo of a baby. The recipient of this picture could then quiz Facebook about it: Is there a baby in the photo? (Yes.) Where is the baby standing? (In a bathtub.)

Facebook even wants to have its AI vision predict what will happen next, which it illustrated with a highlight reel of an algorithm predicting whether or not a stack of blocks will fall — as Schroepfer joked, “We’re doing all of this AI research to teach computers to play Jenga.”

Vreach out and touch someone

The last bit of Schroepfer’s talk involved virtual reality, something Facebook took seriously enough to spend $2 billion to buy the VR-headset developer Oculus. He focused on making VR not just an experience of sight, but one of touch — courtesy of the Oculus Touch gloves introduced this summer.

In a demo clip, two Touch users played VR Ping-Pong, then switched to playing catch with candles and other more interesting objects. “You have these amazing experiences with this person,” Schroepfer said, “even if they’re not anywhere near you geographically.”

In a later Web Summit talk, Oculus founder Palmer Luckey emphasized the difficulty of making VR a tactile experience: “It’s going to be a long time before I can feel this couch and it really feels the same,” he admitted.

But Luckey also closed by saying, “Virtual reality is potentially our best shot at a real post-scarcity economy,” so he doesn’t seem too daunted by the technical challenge.

Will all this technology ever empower us to learn anything from our endless Facebook arguments over politics, sports, and food? I’d ask M, but I don’t have access to that feature yet.

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.