That Delta Plane Flying Straight Through Hurricane Irma Was NBD

There are some places that feel very safe. Like your bed. Or a corner booth at your favorite diner. Or Mom's kitchen table. There are some places that feel very unsafe. Like in a commercial airliner in the middle of one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded.

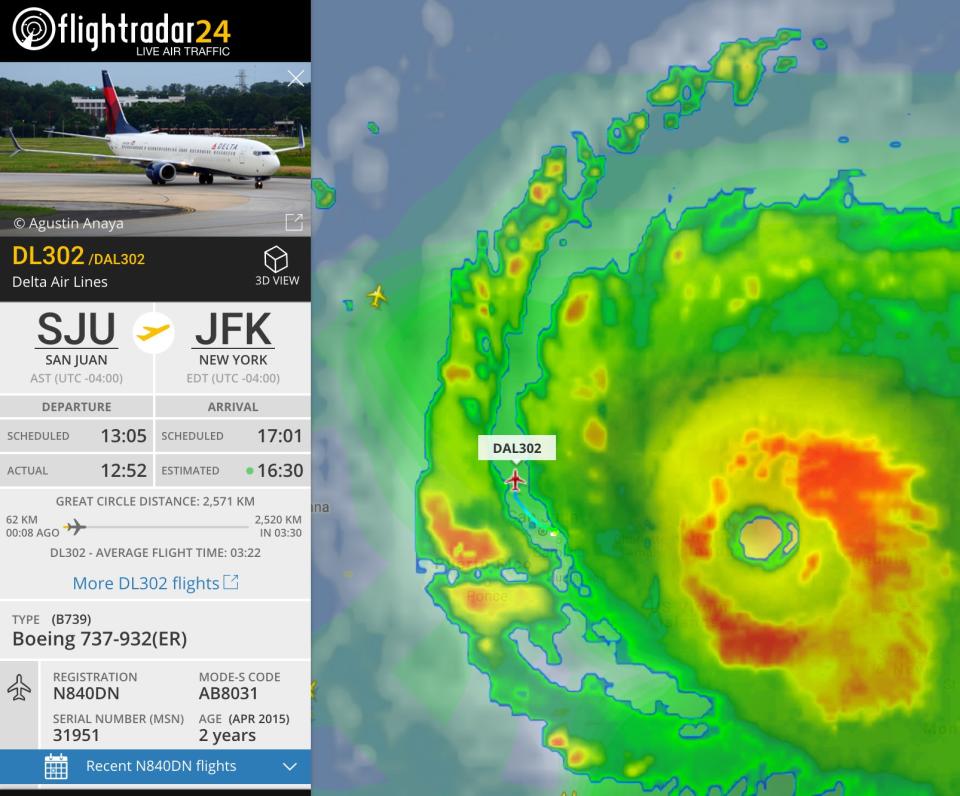

But that's where 173 Delta passengers, plus flight crew, found themselves Wednesday afternoon. Delta Flight 302, the last commercial airplane to fly out of San Juan before the airport shut down amid 185 mile-per-hour winds, rocketed out of Puerto Rico's San Juan Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in between bands of Category 5 Hurricane Irma. The flight safely made it to New York's JFK International Airport less than three and half hours later.

Sounds terrifying, but according to flying experts, it’s NBD. Sure, there are a few tricks to piloting a Boeing 737-900ER around a devastating hurricane, “but it’s not that much different from flying through Midwest in the summertime with thunderstorms,” says Douglas M. Moss, a commercial pilot and aviation consultant with AeroPacific Consulting. “It’s the same techniques, the same tools, the same procedures you use for avoiding thunderstorms.”

In fact, the real daredevil work happened before takeoff—and even before the plane landed in San Juan. As the Delta flight chugged toward Puerto Rico for its scheduled landing at 12:08 pm, Delta’s meteorology team and the folks at its sophisticated command center opted not to turn back to a safer clime—Miami, perhaps?—and decided to steer toward the storm.

“They took a hard look at the weather data and the track of the storm and worked with the flight crew and dispatcher to agree it was safe to operate the flight," Erik Snell, who oversees Delta's operations and command center, said in a statement. (Delta notes the wind gusts in the area were up to 31 knots, "well below operating limits for the 737-900ER.")

Once the plane landed in San Juan, the alternative—leaving the plane on the tarmac or in a hangar—would probably have destroyed the airplane. “It’s awful hard to keep an airplane that big down to the ground permanently, so it doesn’t move and doesn’t move into other airplanes or into the terminal,” says Pete Field, a former Navy test pilot. “Even a Boeing 737 could be wrenched around.” If the plane had gotten stuck, Delta probably could have gotten the humans out safely. But it almost certainly would have lost a plane.

To get Delta Flight 302 into Puerto Rico and out again before Irma’s full force hit the airport, the airline had to carefully orchestrate a plan. The pilots are important here, but so is the ground personnel. Air traffic control had to stay on the scene, as did the fueling equipment and ground support staff. The flight crew had to get passengers off and then on. And you thought the crew hurried you onto your last flight.

In fact, it was that in-between time on the ground—a mere 40 minutes—that was probably most dangerous for the Delta pilots. “When you rush things is when you make mistakes,” says Moss. “I bet their adrenaline was pumped up.”

Up in the Air

Aviation

Taking off is easy. Landing, not so much.

Aviation

It doesn't time travel, but it could get you where you want to go much quicker.

Sky Writing

A tribute to the loyal #AvGeeks.

Once the airline decided to take off, though, the actual process would have been de rigeur. Moss estimates the Delta pilots would have used maximum takeoff thrust, which is harder on the engine, uses more fuel, and is louder than normal, but also helps the plane accelerate faster and makes it easier for it to climb out and into the sky. That, along with a lower wing flap setting, are standard moves for taking off amidst wind shear—abrupt changes in wind speed and direction over a short distance. In other words: what you might expect from a storm.

From there, the Delta pilots would have used their team on the ground and their on-board radar setup to avoid heavy pockets of rain and wind. (That’s the scary stuff in red). Based on the radar readings, the plane had plenty of time to navigate and reach clear skies at around 20,000 feet. “Looks like it was a nip and tuck thing,” says Field. “They got out before it got too hateful.”

The flight might have been bumpy for about 15 minutes, a bit rainy and a bit dark. For the seasoned traveler, conditions like that are probably NBD.