Cuba Unplugged: An Island Still Stuck in Airplane Mode

I’m walking along 23rd Street in Havana, toward the seawall. The wind from the water is blowing the rain horizontally at my face, but I’m desperate to score. It’s been 96 hours, and finding a connection is all I can think about. To my left, a row of about 40 locals huddle together on a dirty sidewalk, catching what shelter they can from the overhang of a valet parking structure. They don’t even look up as I pass them.

Since I’m wearing a red, white, and blue plastic raincoat — the only waterproof thing I brought with me — it’s pretty easy to figure out where I’m from and what I want.

A man in an orange polo with a popped collar leans toward me. His gelled Mohawk is somehow impervious to the rain. “Tarjeta,” he whispers. “Tarjeta, Yuma?” Do you need a Wi-Fi card, foreign lady?

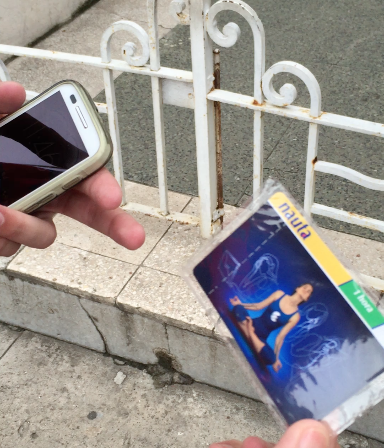

I nod my head gratefully and hand over the equivalent of $3 in soggy local currency. He passes me the card — exactly the size of a credit card but thinner. On one side, there’s a picture of a pretty yoga instructor meditating blissfully. On the other, instructions for how to get connected to a local Wi-Fi access point.

(All photos by Lara Naaman/Yahoo Tech)

I huddle under the parking garage with the row of hunched-over people staring at their phone and tablet screens. Then, for the first time in four days, I switch my phone out of airplane mode. (Cuba’s national phone company has roaming agreements with most major international carriers — excluding most from the U.S.)

After my phone has connected to the Wi-Fi access point, I type a 12-digit login and a separate 12-digit password. I wait 5 seconds for the code to authenticate, and then get my first email since taking off from Miami.

“LAMAR ODOM IS OUT OF A COMA!” (The Kardashians have not yet Konquered Kuba, so I actually had been wondering about poor Lamar.)

The second email says, “Not panicking yet but please let me know if you are alive.”

The third: “Haven’t seen any Instagram pics of your trip. Have you been murdered?”

A text from my dad: “ARE YOU HOME FROM CUBA PLEASE CALL DAD.”

Partying like it’s 1997

While 96 hours of Internet darkness is tantamount to death in the U.S., it’s beyond normal for the majority of Cuba’s 11 million citizens. They were barred from buying computers and cellphones until 2008.

A trip to Cuba is a trip back in time to many different decades at once. The meticulously maintained classic cars take you back to the ’50s. The crumbling art deco buildings take you back to the ’30s. And the Internet access takes you back to about 1997.

The notoriously restrictive nation just got public Wi-Fi back in July. There are 35 access points on the island and 5 in the capital city of Havana. That’s a start, but getting online is neither cheap nor fast. You can get access at one of the fancier hotels for about $10 per hour. If you want to wait in a long line at the national telecom office, Wi-Fi cards cost a more budget-friendly $2 for an hour (still prohibitive for the average Cuban, who makes $20 a month). If you want to buy the card from a dude on the street whispering “Wi-Fi card, Wi-Fi card,” it’s $3.

As an Instagram addict who uploads around 20 photos a day, I was in complete denial about my Internet prospects when I boarded a charter flight from Miami this past month. I’d read plenty of warnings about the limits on access but figured that just meant checking my email a bit less. “I’ll just pop into a hotel whenever I pass one,” I thought.

Now, without Wi-Fi or cellular roaming, it took me a few days to figure this out because, well, I had to actually ask people rather than just do a search on my phone.

Not that Cubans are oblivious to the Internet. Universities and a handful of select professions have had dial-up access for years (and many “unauthorized” methods of getting content have sprung up to meet demand). But only an estimated 5 percent of the population has access to the greater World Wide Web, as opposed to a shadow Intranet or thumb drives of bootleg Netflix.

So the Internet as we know it isn’t the pervasive cultural force there that it is in the rest of the world. As one new Cuban friend put it, “Our entire country is in airplane mode.”

Does my smartphone make me look rude?

Aside from the greater social implications, that means some etiquette violations are bound to occur when you mix Cubans with outsiders.

One evening I was dining with three tech entrepreneurs, the owners of the electronic cultural guide Ke Hay Pa Hoy. They are smart, well-mannered, witty young guys, not long out of college. As we sit down to eat, I absent-mindedly put my phone on the table right next to my fork. They exchange bemused glances.

“Is something very important about to happen?” asks Juan Alejandro, a fashionably dressed guy sitting to my left. “Are you expecting a critical call on the phone which — you just complained — doesn’t actually work?” (Their phones are all politely out of sight.)

Less than a quarter of the population has cellphones in Cuba. They don’t have unlimited plans like we do in the U.S. They pay for each call and text. Actual phones are usually secondhand gifts from family abroad — you still see flip phones as much as smartphones.

Emboldened by my poor etiquette, my tech-savvy new friends take out their Samsung Galaxies and iPhones and show me the many apps they use that are optimized for offline use: maps, news feeds, and their own entertainment guide.

Then, as a plateful of gorgeous lobster tails arrives at the table, all the Americans grab their phones, stand up, and snap pictures of the food like it’s Angelina Jolie and we’re paparazzi.

“What’s happening?” exclaims Sergio, the outgoing leader of the tech triumvirate. “Why are you all taking pictures of the food?”

Turns out Instagram isn’t big there yet, either.

“You mean you take a picture of food, you put it on the Internet, and then people actually want to look at it?”

“Yes,” I admit sheepishly. “And then … they LIKE it.”

(Despite their skepticism, we’re all following each other on Instagram now.)

Another example of the tech divide popped up during a conversation with Rocio, our stylish young tour guide.

“This wireless phone charger is so tiny it’ll fit in any purse,” I tell her. “You can get it on Amazon! I’ll send you the link.”

Sighs from all Cubans present.

“We don’t have online shopping.”

Cuba Internet Libre

In the six days I spent in Havana, I was at least able to answer the question, “What did we do before cellphones and the Internet?”

We got lost more often and had to stop and ask other humans for directions.

We showed up at the right place, at the right time, because we couldn’t just text and say, “Oops! Traffic. Sorry!” Or, “I’m actually 5 blocks away at this really cool bar can’t you just come here instead?”

We argued more. You can’t instantly win an argument about the first Cuban film to be nominated for an Oscar, because you can’t just plug it into your phone and show it to your opponent. (It was Fresa y Chocolate. I was right. I knew I was right.)

Awkward situations lasted longer. When your phone isn’t connected to anything, you can’t pretend you just got an urgent call and leave.

This may all soon change. This past summer, plans by Cuba’s Ministry of Communications to expand Internet access were leaked. Current goals include expanding broadband access to 50 percent of homes by 2020, with a price of less than 5 percent of the average monthly salary.

Midway through my trip, I spoke to a woman of about 65, who had been renting out rooms in her house for years but was finding a new American clientele with the introduction of Airbnb in Cuba.

She was generally positive about how technology was helping her expand her lodging business. I asked her if she had any fears about the changes that a more open Internet might bring.

“I’m not afraid of change,” she responded. “Things have to change. They haven’t changed for so long. We welcome whatever comes.”

“What if I told you that in America we use the Internet mostly to watch videos of cats?”

There was a long awkward silence.

“How terrible,” she said.

Lara Naaman is a video producer and travel writer. When she’s not traveling the globe, she lives in Brooklyn with her cat, Jack Bauer Supercat Naaman.