The Army’s Scout Helicopter Is Cursed

The U.S. Army startled industry observers on Thursday when it revealed that it was pulling the plug on its advanced new Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) scout helicopter program—even as teams at Sikorsky and Bell were preparing rival prototypes named Raider-X and 360 Invictus for their first flights.

The Army’s decision comes as a shock. FARA was a high-profile program six years in the making on which $2.4 billion had already been spent. And unlike many other canceled programs, FARA hadn’t entered a death spiral of cost overruns and delays. Until Thursday, the Army’s messaging had been full tilt forward.

But from a longer view, FARA’s ignominious end isn’t all that surprising. This is now the fourth failed attempt by the Army to field a new scout helicopter in the last three decades. That the Army even launched FARA in 2018 raised eyebrows—high-risk tactical aerial reconnaissance, target designation, and strikes along frontlines saturated with anti-aircraft weapons are almost exactly the missions that armies are using drones to perform today. It seems like the thought is: better a drone than a large, expensive aircraft with humans on board.

Two years of high-intensity ground warfare in Ukraine has provided further evidence that drones, not manned helicopters, are the most viable for tactical recon/light attack missions. And indeed, after belatedly conducting an “Analysis of Alternatives (AOA) for FARA under congressional pressure, the Army concluded that “satellites and small drones” would be able to perform FARA’s mission more affordably.

“We are learning from the battlefield—especially Ukraine—that aerial reconnaissance has fundamentally changed,” Gen. Randy George wrote in a press release. “Sensors and weapons mounted on a variety of unmanned systems and in space are more ubiquitous, further reaching and more inexpensive than ever before.”

UH-60V cut, ITEP Delayed but Chinook Block 2 is Back

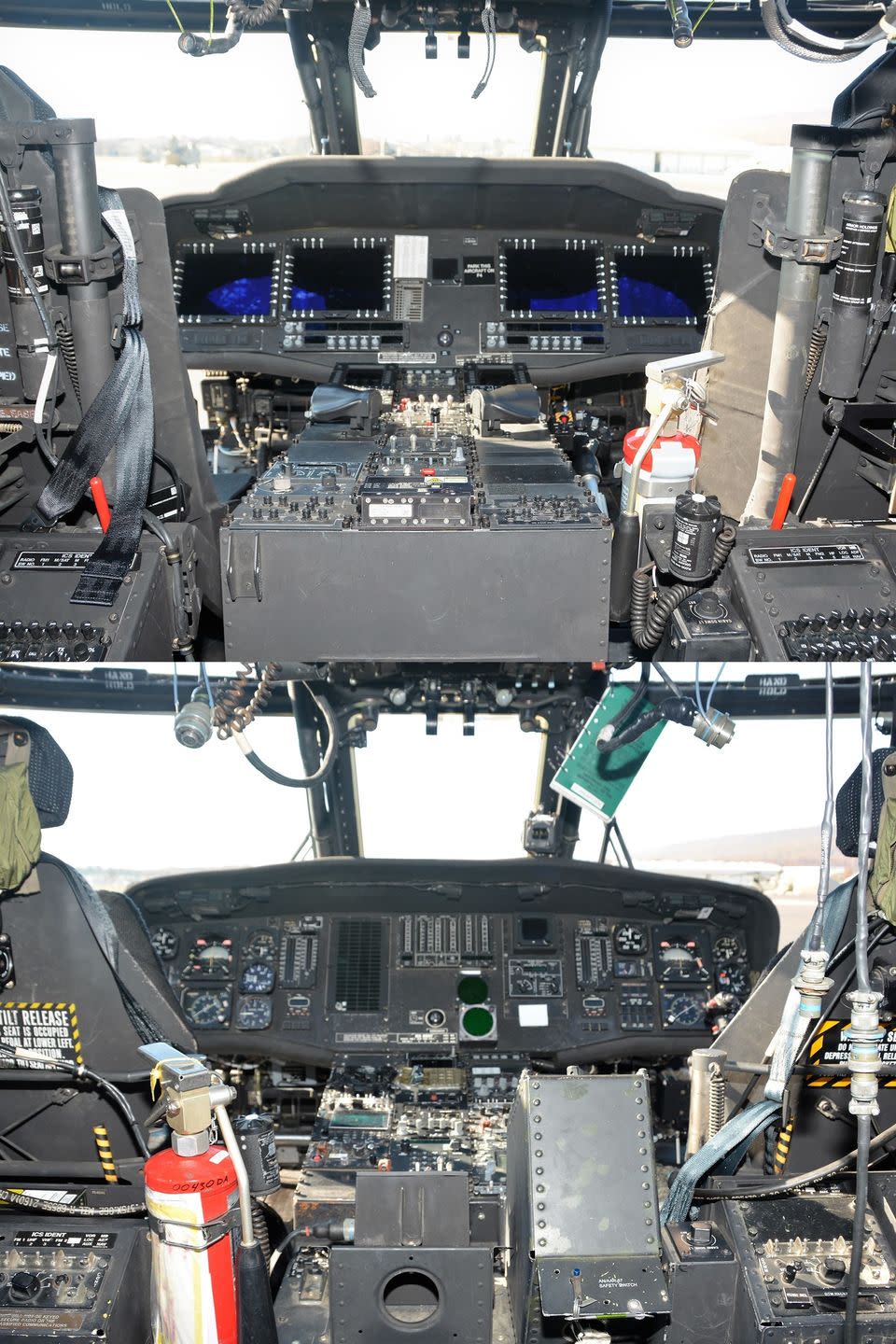

Another program on the chopping block was the UH-60V, which might sound like a hyper-advanced version of the mainstay UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter. But, in fact, it’s a retrofit of old UH-60L helicopters, with the ‘glass cockpit’ instrumentation of the current standard UH-60M model.

Despite 70-80 UH-60Vs being delivered by Northrop-Grumman primarily to three Army National Guard aviation brigades, in 2023, the Army demurred on ordering full production for the planned total of 768 UH-60Vs. The service now cites rising program costs for canceling UH-60V refits, and instead plans to issue multi-year orders for additional new UH-60Ms.

The program to re-engine Army UH-60Ms and AH-64 Apaches with the Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP) that was also intended for FARA was delayed another year, having originally been scheduled for fall of 2023. The General Electric T901 turboshaft generates 3,000 shaft horsepower—roughly 50% more than the current T700 and T701 engines. It’s unclear whether FARA’s cancellation will undermine ITEP, or if it will be procured later.

It’s not all bad news for Army aviation. The service has committed to purchasing new Boeing CH-47F Block II Chinook heavy transport helicopters after halting procurement in 2018. These feature 20% more powerful T55-715 engines, new fuel and rotor actuator systems, and increased power generation. These enable better performance in hot or high-altitude conditions and the ability to carry heavier loads, including JLTV trucks. The first six CH-47F Block IIs procured cost $199 million between them, or $33 million apiece.

The Army’s brigade-level RQ-7 Shadow and company-level RQ-11 drones will also see expedited retirement and be replaced by newer drones that were ushered in from the Army’s FTUAS competition, with flying prototypes and production orders expected by 2025. The service is also looking at three different “launched effects” drones of varying range designed for release by other Army aircraft.

The crown jewel of Army aviation modernization remains secure: the long-range, high-speed tilt-rotor assault transport (FLRAA) based on Bell’s V-280 Valor—now accorded a bigger pool of money with FARA’s demise. This design could eventually spawn an armed reconnaissance variant without necessitating the development of an entire new design. Bell is therefore less adversely impacted by FARA’s cancelation than Sikorsky, which has yet to secure a win for its compound-rotor designs.

The Army’s thrice-cursed scout helicopter procurement

The Scout helicopter arose in the 1950s and 60s as a more flexible successor to pokey “army cooperation” light planes used during World War II for reconnaissance, officer transport, and spotting targets for air and artillery strikes. Helicopter scouts also led to fielding armed helicopters—initially with machine guns and rocket pods, and later with anti-tank missiles.

Arguably, the Army’s two most important armed scouts during the Vietnam War were the diminutive OH-6 Cayuse ‘flying egg’—which suffered 59% losses—and the larger Minigun-armed OH-58A Kiowa, based on the civilian Bell 206 JetRanger helicopter.

Both saw plenty of action post-Vietnam, with a variant of OH-6 (the MH-6 Little Bird and AH-6) dedicated to special ops attack and insertion roles. Army light attack/reconnaissance units, on the other hand, adopted the ultimate OH-58D Kiowa Warrior model, with its distinctive laser designator mounted atop its rotor and wing stubs for carrying rockets, Hellfire missiles, and guns. The Kiowas soldiered on in the light attack, observation, and target designating roles—flying roughly half of all attack/reconaissance missions in Iraq and Afgahnistan, with 35 lost to enemy fire and crashes in the 2000s.

In the 1990s, the Army planned to replace the OH-58 with the sleek, agile, and stealthy RAH-66 Commanche, with attack-helicopter-like characteristics. But Commanche was pricey, and interest in such an elaborate war machine was lacking during the counter-insurgency-focused ‘War on Terror’ in the 2000s, leading to cancelation in 2004 after $7 billion was spent building several flying prototypes.

Then, in 2005, the Army awarded Bell a $2.2-3 billion contract for 368 of the cheaper, more Kiowa-like ARH-70 Arapahos, a conversion of the Bell 407 civilian helicopter. But following a series of flight delays, a 70% projected cost increase, and a controlled crash of the prototype, Arapaho was cancelled in 2008.

Next, in 2013, the Army was poised to spend $10 billion for 368 upgraded OH-58Fs (the vast majority remanufactured OH-58Ds), based on a prototype that the Army had built on its own initiative. Intended to serve through 2036, the OH-58F featured new sensors and cockpit displays, enhanced armor, and improved flight performance from weight savings. A follow-on Block II upgrade would have featured a new engine and components from the Bell 407 and 412 helicopters.

However, during the funding-scarce 2010s, the Army canceled OH-58F and decided to retire its entire Kiowa fleet—concluding that new AH-64E Apache Guardian attack helicopters teamed up 2:1 with MQ-7B drones could assume the Kiowa’s mission.

Kiowa Warriors were finally fully retired in 2017, with 110 of them purchased by Croatia, Greece, and Tunisia. OH-58Cs used for training retired in 2020.

Once the service actually began using Apaches in the scout role, it concluded that they were a poor substitute, due to the costs of operating heavy attack helicopters being much higher than the cost of operating the retired Kiowas. That dissatisfaction led to FARA’s inception in 2018, and the down-selection of Bell and Sikorsky in March of 2020.

The Scout Helicopters that Might Have Been: 360 Invictus and Raider-X

The Army’s FARA requirements were for a fast helicopter cruising at over 235 miles per hour using the Army’s new T-901 turboshaft engine, with four rotor blades small enough that it could squeeze in between city blocks (no larger than 12 meters in diameter). It needed a combat radius of 155 miles or more, and the capacity to optionally fly without onboard crew. Each individual helicopter was to cost no more than $30 million (roughly the price of an Apache) and $4,300 per hour flown.

Within those parameters, Bell and Sikorsky obligingly developed two strongly contrasting designs.

Sikorsky offered up another compound helicopter called Raider-X (derived from its S-97 Raider), with two rotors stacked on top of each other and a single, rearward-facing pusher propeller. Their 7-ton design featured side-by-side seating for the pilot and co-pilot, and was expected to achieve a maximum speed of up to 290 miles per hour—a staggering 60 percent faster than a Blackhawk or Apache. It also has the spare capacity to haul six passengers. (Though armed scouts aren’t intended to transport personnel, the OH-58’s ability to carry a couple passengers in a pinch occasionally proved to be a life-saver on the battlefield.)

Bell’s 360 Invictus prototype was a more conventional design—derived from its civilian twin-engine Bell-525 Relentless super-medium lift helicopter, but with a lean Commanche-like profile (including the tandem seating arrangement). It sports a chin turret with a 20-millimeter cannon, optics, a laser rangefinder, and side-retracting missile launchers (to reduce drag).

Unfortunately, delays producing T-901 engines—with the only two delivered in 2023 given to the FARA competitors—had a spillover effect on getting the prototypes into the sky.

Both aircraft look like impressive designs. Even canceled, they may yet actually fly—or, at least, see further R&D—as funding will not technically be cut for FARA until October of 2024 to soften the blow to the industry.

FARA was already arguably an anachronism, given the increasingly mature and diversified capabilities of drones to perform reconnaissance missions, target designation missions, and targeted precision strikes.

The war in Ukraine, in this regard, has been revelatory. While attack helicopters have gotten their licks in on occasion, they’ve also suffered heavy losses and must release weapons from far back to maintain acceptable survival odds. And no observer of the war could dispute that drones (rangig from small civilian quadcopters and cheap first-person-view kamikazes to larger military fixed-wing surveillance drones) have performed the majority of the tactical-level reconnaissance and air strikes in the war by far.

Certainly, while still valuing attack helicopters, neither Russia nor Ukraine is desperate to field scout helicopters. Furthermore, such short-range helicopters would lack the range to truly participate in a fight on the Pacific Ocean—ostensibly the Pentagon’s current focus.

Admittedly, compared to most drones, an armed scout helicopter can combine additional weapons and sensors in a formidable, non-jammable package. But that’s a big, expensive package with humans on board. Given modern costs and sensibilities, the Army can’t afford to risk these on the battlefield in the way it lost hundreds of scout helicopters in Vietnam.

Until then, money from FARA can now go to supporting FLRAA and current-generation aircraft with decades of service ahead—i.e. the Apache, Blackhawk, and Chinook—more robustly. In theory, the Army will also use freed-up funding to field a new generation of less costly, unmanned reconnaissance and strike aircraft that it can deploy in larger volumes, informed by the revolution in drone warfare observable in Ukraine.

You Might Also Like