These Ancient Bricks Exposed a Dramatic Change in Earth’s Magnetic Field

Ancient bricks may be key to understanding Earth’s variable magnetic fields.

Scientists examined the iron oxide levels of 3,000-year-old bricks to understand the level of magnetism the bricks were exposed to at the time they were fired.

The strategy could be a new way to date ancient artifacts void of organic matter.

Ancient bricks can apparently tell the story of dramatic shifts in the strength of Earth’s magnetic field, opening up a new world of artifact dating.

A team of researchers, who published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed how the ebb and flow of Earth’s magnetic field remains imprinted on 3,000-year-old Mesopotamian clay bricks thanks to changes within the iron oxide grains. Excitingly, this data could bet the start of an entirely new method of dating ancient artifacts void of organic matter.

“We often depend on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia,” Mark Altaweel, co-author and archeology professor at University College London, said in a statement. “However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot typically be easily dated because they don’t contain organic material. This work now helps create an important dating baseline that allows others to benefit from absolute dating using archaeomagnetism.”

This new term, archaeomagnetism, refers to the signature of the Earth’s magnetic field in archaeological items. Not only can it help with dating artifacts, but may also teach experts more about the history of Earth’s magnetic field, which changes in strength over time.

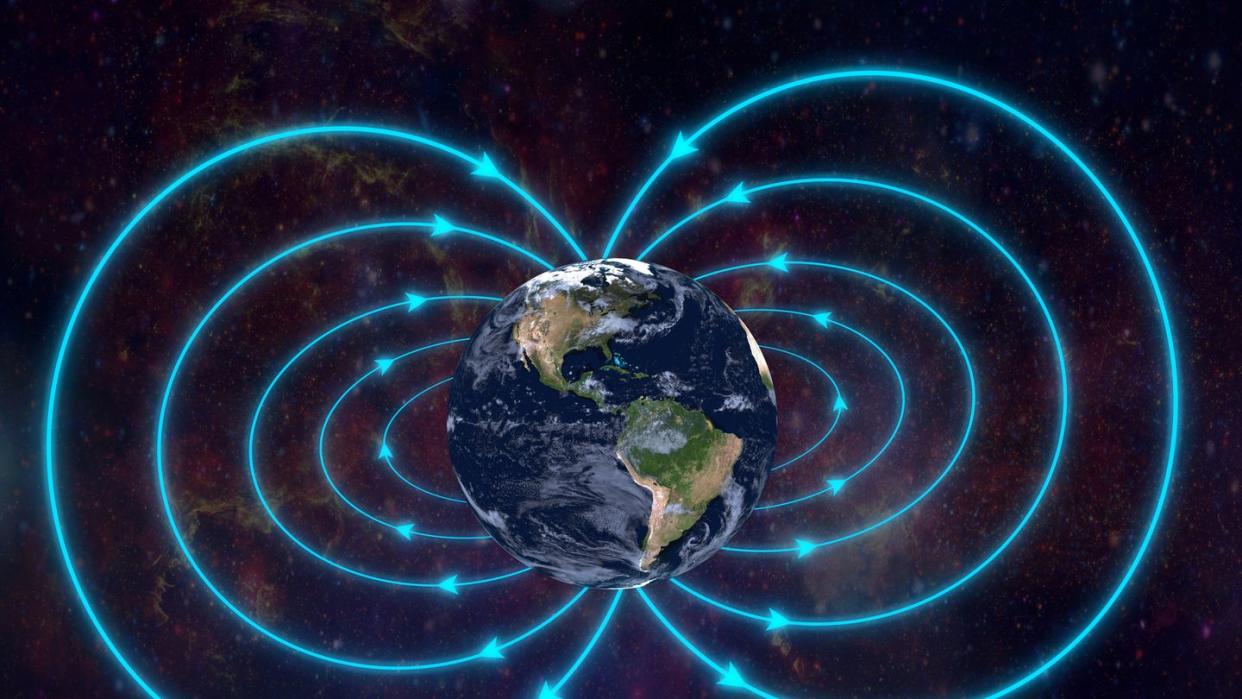

It turns out that our planet’s magnetosphere imprints a distinct signature on minerals, such as iron oxide, as they are heated. So, when workers fired clay bricks, they were locking in evidence of the relative strength of Earth’s magnetic field for all of time.

Finding the strength of the magnetic field by itself—without something to tie it to—may help us better understand the history of our planet, but it doesn’t help much with dating the artifacts being examined. To do that, the team chose 32 bricks from archaeological sites throughout the region that used to be Mesopotamia, each inscribed with the name of a reigning king.

“The well-dated archaeological remains of the rich Mesopotamian cultures, especially bricks inscribed with names of specific kings, provide an unprecedented opportunity to study changes in the field strength in high time resolution,” Lisa Tauxe, co-author and professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in a statement, “tracking changes that occurred over several decades or even less.”

It wasn’t an easy process. Analyzing the iron oxide grains meant studying tiny fragments from the broken faces of the bricks and employing a magnetometer to precisely measure those remains.

“By comparing ancient artifacts to what we know about ancient conditions of the magnetic field,” Matthew Howland, lead author and Wichita State University professor, said in a statement, “we can estimate the dates of any artifacts that were heated up in ancient times.”

It may not have been simple, but it was successful. Mapping the measured magnetic strength of the iron oxide grains to the imprinted name and known time of that person’s rule allowed the team to create a historical map of the shifts in the magnetic field. Combining science and history in this way allowed experts a unique look into the past—both of the object being analyzed and of our planet.

And it turns out that using the timelines of the kings—some of whom had reigns that lasted only a few years—can provide an even narrower dating window than radiocarbon dating, which often only can get within a few hundred years.

This new ancient map also highlighted some unique occurrences in our planet’s history. It managed to confirm an event known as the Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic Anomaly—when the magnetic field was unusually strong from about 1050 to 550 BC. It also showed a dramatic change in the field over a relatively short period of time during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II) from 604 to 562 BC), offering evidence that rapid spikes in intensity within our magnetic field can—and do—occur.

“This research,” the authors wrote in the study, “establishes a baseline for the use of archaeomagnetic analysis as an absolute dating technique for archaeological materials from Mesopotamia.”

You Might Also Like