Why There Is So Much Sugar in Your Kid’s School Breakfast

Bettina Elias Siegel for Civil Eats

“Whole grain rich” pop tarts (made with at least 50 percent whole grains) are allowed in school breakfast programs; PHOTO: Shutterstock/Jamie Duplass

When my kids’ Houston school district instituted a free in-class breakfast program five years ago, it did so for all the right reasons. Over 80 percent of the students were coming from economically disadvantaged homes, and the district understood that hungry children simply can’t learn effectively. And while Houston had long offered free breakfast in the cafeteria before the first school bell, a variety of obstacles — parents’ work schedules, late school buses, even feelings of shame and stigma — had kept a significant number of hungry kids away.

By moving the food to rolling carts in school hallways, Houston now allows students to grab breakfast and eat it at their desks during the first few minutes of class. That simple change has yielded some significant pay-offs: Breakfast participation increased from 45 percent in 2006 to almost 80 percent within just the first year of the roll-out; attendance reportedly improved; discipline problems reportedly declined; and some test scores went up, at least initially. But in the midst of all that good news, there’s still an elephant in the classroom: The food itself is often highly processed and full of sugar.

MORE: 5 Things to Know About the Congressional Battle over School Lunch

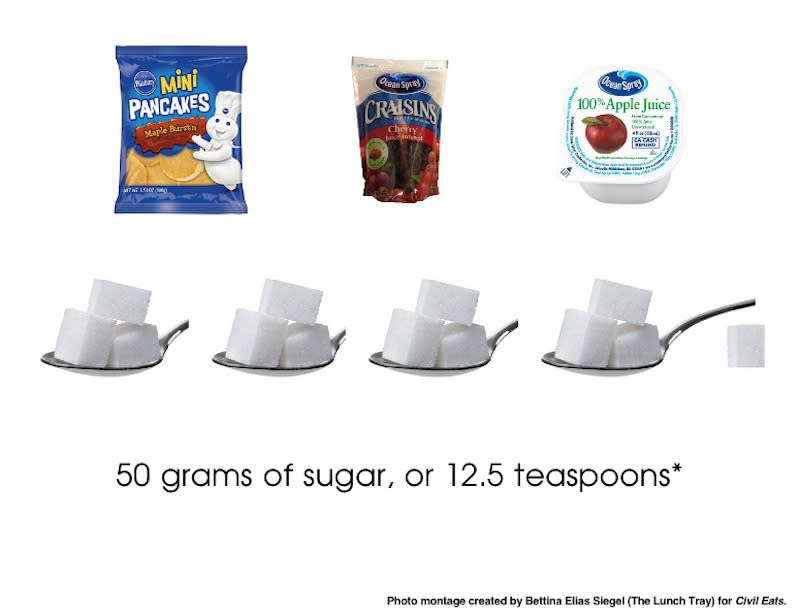

Here’s the September breakfast menu in our school district. Students select a minimum of three of the offered items (which also include milk); depending on what a child picks, it’s possible to create a meal with up to 39 grams, or almost 10 teaspoons, of added sugar. (The American Heart Association says children should have no more than 3-4 teaspoons a day.) If apple juice’s naturally-occurring sugar is included in the calculation, that number can shoot to 51 grams, or almost 13 teaspoons. Here’s an example:

Because apple juice is devoid of fiber, its naturally-occurring sugar grams are included here. But even without the juice, this meal contains 9.5 teaspoons of added sugar; PHOTO MONTAGE: Bettina Elias Siegel

This district is hardly unique. Notably similar breakfast menus can be found in districts as far afield as Nashville, San Diego, Little Rock, Albuquerque, and Baltimore. As Beth Collins, Director of Operations at the Chef Ann Foundation, notes of such offerings, “Juice is very prevalent, along with dried fruit and canned fruit. Paired with the never-ending varieties of pancakes-on-a-stick, waffles, and similar items, kids are literally sugar bombed at breakfast. And it’s all ‘legit’ under the regs.”

But weren’t nutritional requirements for school meals overhauled under the 2010Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA)? Yes, but there are a variety of reasons why breakfast can still fall short.

A Glaring Omission in the School Food Law

Though the new guidelines set long overdue limits on sodium and calories, while adding new requirements for fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, the law contains a notable omission: There is no cap on added sugars in school meals. As a result, according to the Center for Investigative Reporting, “sugar levels in school meals are more than double what is recommended for the general public.”

Why is there no limit on added sugars? While some health advocates did urge the U.S. Department of Agriculture to include such a limit, that effort was hampered by the fact that the Food and Drug Administration’s Nutrition Facts label doesn’t (yet) disclose levels of, or set a Daily Value for, “added sugars.” As Margo Wootan, Director of Nutrition Policy at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, recalls of the HHFKA rule-making process, “The main barrier to a limit on sugars in school meals was the lack of a Daily Value on which to base the recommendations.”

MORE: Amidst School Lunch Fight, Paid Mom Bloggers Shape the Conversation

While the new law didn’t limit sugar, it did impose overall calorie caps on school meals. But that hasn’t necessarily led to the removal high-sugar foods. School breakfasts don’t have to contain a protein component, such as meat or a meat substitute. So when a meal consists only of fruit, a sweetened, highly-processed grain item, and milk, it’s entirely possible for sugar to account for a substantial portion of the total allowed calories. “In my experience,” says Collins, “the only people really looking at the sugar are the parents, school nurses, and kids who need to track the carbs for their insulin management.”

The Need for Speed

Houston may have been in the vanguard of the in-class breakfast movement, but the program is now being adopted by a growing number of districts around the country. As a result, grab-and-eat convenience has become more important than ever to schools and, not surprisingly, Big Food is there to fill the need.

MORE: The Real Reason Your Kids Are Still Seeing Junk Food Ads

Leading companies such as Kellogg’s, Sara Lee, and General Mills, as well as countlesssmaller players, offer an array of highly processed and often sweet breakfast items, including Eggo Bites, miniature cinnamon buns, and strudel bars, any one of which can go a long way toward filling a young child’s recommended daily quota for added sugar. Flavored yogurt is another popular option, a food so highly sweetened that journalist and author Michael Pollan has referred to it as our food supply’s “latest sugar delivery system.” And, of course, many schools also offer chocolate milk with breakfast as well.

“America’s love affair with sugar and especially sugary breakfast cereals, pastries, and beverages has unfortunately segued into school breakfast,” adds Chef Ann Cooper, who heads the school food program in Boulder, Colorado (and is the person after whom the Chef Ann Foundation was named).

“More Fruit” = Juice and Craisins

Another surprising driver of sugar in school breakfasts is, ironically, a new requirement that kids be served more fruit. Under the old nutrition rules, schools offered a half-cup of fruit at breakfast, but kids were allowed to pass it up. Now schools have to offer a full cup of fruit and kids need to take at least a half-cup serving. That sounds great on paper, until you learn that districts are allowed to swap 100 percent juice for half of the fruit quota. Many health experts believe juice consumption contributes to childhood obesity due to its high fructose content and lack of fiber, yet for both districts and kids, that juice loophole is often simply too tempting to pass up.

MORE: What Happens When You Teach Math in the Garden?

Juice is usually shelf stable and easy to store and serve, while fruit is perishable and can require preparation and/or messy peeling by students. Moreover, serving the one-cup quota of whole, fresh fruit can be complicated. Collins explains that “a given variety of orange might not be a cup equivalent—maybe it’s only 5/8—so a school would still have to offer something else, like juice, to comply.” And, finally, many district milk suppliers make juice ordering and delivery a breeze. As Collins notes, “It’s quite common that the juice is delivered with the milk by the dairy provider, and those deliveries are often frequent. So especially in the smaller districts that don’t have warehouses and centralized systems, juice becomes a major player at breakfast.”

For students, juice is often the default choice over fresh fruit, which can sometimes be rock hard, flavorless, or difficult to eat in the short time allotted for breakfast. Audene Chung, Houston ISD’s senior administrator for Nutrition Services, confirms: “Our plate waste studies have shown that our students are more likely to throw away fresh fruit, but will drink fruit juice.”

MORE: How One Visionary Changed School Food in Detroit

As for the remaining half-cup of fruit, many districts opt for dried fruit because it, too, is shelf-stable, and generally popular with kids. But while dried fruit is a better choice than juice because it contains fiber and has an intact cellular structure, it also has more sugar (albeit naturally occurring) than fresh fruit. And when dried fruit takes the form of Craisins, which are made with a significant amount of added sweetener, breakfast can become a real sugar frenzy. Collins has observed that many schools also rely on canned fruit, which she describes as “another sugar monster.”

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul

Finally, and perhaps most important, is the issue of cost. Schools in compliance with the new nutrition standards receive an extra six cents per lunch served, but no additional funding for breakfast. That has led many school food professionals to complain they’ve been saddled with an unfunded mandate and it has incentivized them to cut breakfast food costs wherever possible. Since healthier, low-sugar food is often more expensive, that cost-cutting goal often means more highly-processed food.

But in districts serving an in-class breakfast to a high percentage of needy kids, the meal can actually be cash-positive if food and labor costs are kept relatively low. And when federal reimbursement exceeds the total cost of the meal, that extra money can be used by school nutrition departments to cover other expenses such as the food served at lunch, equipment purchases, and payroll. It’s no surprise then that a school food consultant once referred to school breakfast programs as providing “big breakfast bucks” that “can give a meaningful financial boost” to school food departments in needier districts.

MORE: This Pastry Chef Wants You to Eat Fewer Sweets

This phenomenon may explain why our Houston district, which boasts a $51 million dollar state-of-the-art central kitchen intended to “make recipes from scratch,” is still serving our kids pre-packaged mini waffles, Craisins, and juice.

But does it make sense to short-change kids with a high-sugar breakfast in order to improve other aspects of the school meal program? Isn’t breakfast the most important meal of the day?

As school food reformer Dana Woldow told me, “The bare minimum every parent has a right to expect from education is that the school will do nothing to harm their child. Serving a breakfast with so much sugar harms children. It harms their metabolism, their teeth, their waistline, and their ability to focus in class when that giant sugar rush wears off —just as teaching begins.”

This article originally appeared in Civil Eats.