Abercrombie & Fitch Tried to Escape Its Body-Shaming, Whitewashed Image. It Couldn’t.

In the 1990s and early aughts, Abercrombie & Fitch dominated the teen apparel market. Its stores, offering a full sensory experience, were a destination, and its clothes — embodying the logo-embossed uniform of the decade — were coveted. Then, something started to change.

Customers seemed to grow tired of the Abercrombie & Fitch song and dance. The stores, they complained, were too dimly lit, the music too loud, and the smells too strong; the advertisements were too sexual, too white. Its then-chief executive, Mike Jeffries, body-shamed shoppers who didn’t fit the model (pun intended) of what he called Abercrombie’s “core” customer, famously telling Salon in 2006: “Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

And then the A&F clothes themselves lost their appeal.

Now, despite a four-year-plus turnaround effort that has largely fallen flat, Abercrombie & Fitch is looking for buyers, exploring the sale of a company that was once the destination for mall-bound teens — not to mention typically jaded New Yorkers, who often stood in long lines just to get inside a favorite Manhattan location.

It doesn’t help that shopping malls in general face a looming death-by-online-shopping, with too many retail locations and not enough foot traffic to sustain them. (As of January, Abercrombie operated 709 stores in the United States and 189 stores internationally.)

But for A&F, the company’s precipitous decline seems to be not only about the retail apocalypse but about becoming so far removed from the cultural zeitgeist that it could no longer connect with the teen masses of its core customer base.

“Abercrombie’s sensibility, the idea of Abercrombie & Fitch, couldn’t be a more polar opposite of what millennials want,” says retail trend analyst Charcy Evers. Before 2014, that sensibility was logomania, ultra-low-rise jeans for hundreds of dollars, and polos in every color of a 64-count Crayon box.

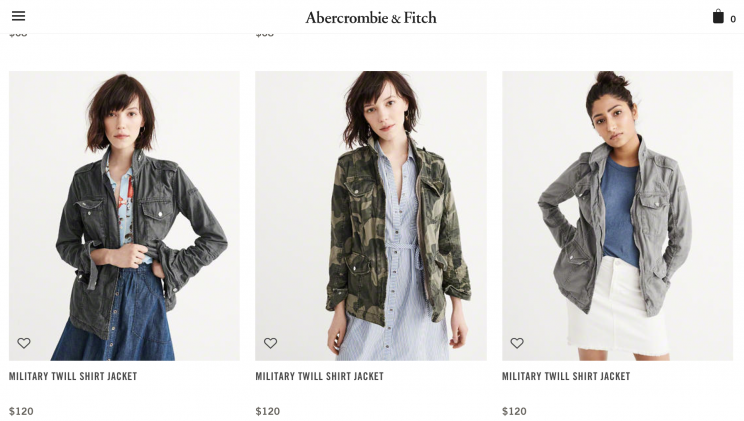

But as the company tried to pivot to meet consumer demands for uniqueness and inclusion, it lost most of what made the Abercrombie brand iconic. “In their desire to tone down who they were, with the overtly sexual images in your face, or the logos, they definitely toned down the aesthetic to make it more pleasing, cleaner,” Evers says. “But in that transition, you look at the site and wonder: Who are you?”

It was, ironically, a fate that Jeffries aimed to have A&F avoid, since he noted in that same 2006 interview that companies with a more inclusive philosophy were boring.

“Those companies that are in trouble are trying to target everybody: young, old, fat, skinny,” he said. “But then you become totally vanilla. You don’t alienate anybody, but you don’t excite anybody, either.”

And in the age of fast fashion, where everything looks the same and retailers are in a race to the bottom to offer the lowest prices, a $120 price tag for a lifeless military jacket appears to be the furthest thing from a hot-ticket item.

Conversely, customers don’t seem to mind paying discounted prices for Abercrombie on resale sites like thredUP, where 81 percent of A&F items listed on the website sell within three months. But resale doesn’t exactly help foster an image of prestige.

Bottom line: Abercrombie can’t blame all its problems on the death of the shopping mall. Because this latest move feels more like social suicide.

Read more from Yahoo Style + Beauty:

Spanx Founder Sara Blakely Shares Empowering Message About Following Your Dreams

Every College Accepted Her: ‘Black-ish’ Star Yara Shahidi Is Hollywood’s Most Stylish History Nerd

Woman Shares Mastectomy Scar and Powerful Message: ‘Representation Matters’

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day. For Twitter updates, follow @YahooStyle and @YahooBeauty.

Alexandra Mondalek is a writer for Yahoo Style + Beauty. Follow her on Twitter @amondalek.