The stories of Cleveland's greatest sporting day

CLEVELAND – Lake Erie is why Cleveland exists, a city built a couple of centuries ago on a perfect port for freighters to haul coal and corn and iron and manufacturing to global markets. The city proper once pushed nearly a million residents, and even as that has dwindled to about 400,000 due to suburban sprawl and economic flight, there are still steel mills here, still barges banging up on the docks at the mouth of the Cuyahoga, still deals being made in the skyscrapers high above.

It’s more than that, though. Lake Erie provides its summer entertainment and its wicked winter winds and its sunsets that bloom across the sky. It’s the soul of the place, the constant.

Tuesday was the greatest sporting day this city has ever known – the Indians defeating the Chicago Cubs 6-0 in Game 1 of the World Series directly across the street from where the Cavaliers held a pregame ceremony to raise the city’s first championship banner since 1964, ending decades of athletic futility and failure.

And on Tuesday morning, Lake Erie served as something else for a native son: atonement perhaps, or at least a measure of ridiculousness, of frivolity to take the heat off a controversy so very uniquely Cleveland.

On Sept. 17, Paul Hoynes wrote a column for the local Plain Dealer newspaper declaring “the Indians were eliminated from serious postseason advancement before they even got there.”

He had good reason for the prediction. That afternoon pitcher Carlos Carrasco broke a bone in his throwing hand, which was just days after catcher Yan Gomes broke his wrist which was just days after pitcher Danny Salazar injured his arm which was just the latest in a pile of injuries that should have ended a once-promising season.

Hoynes knows baseball, having covered the Indians since 1983. Maybe more importantly, he knew Cleveland, having grown up in Cleveland Heights, graduating from Cathedral Latin High School and choosing to spend pretty much his entire adulthood living here.

In Cleveland sports, when things go bad, they stay bad. That has been the rule. The Indians haven’t won the World Series since 1948 after all.

“Maybe that was the Cleveland pessimism,” Hoynes said. “Maybe it was just waiting for the other shoe to drop. You’re sitting there thinking, ‘This is a good team. They’ve got good talent. But they’re going to win their division and that’s going to be it.’ ”

So he wrote the column. The Indians didn’t appreciate it. They pushed back. There was anger. Front-office folks called and told him he was wrong. Players felt slighted, believing he was rooting against them. Fans rallied behind the team. In New York, in Boston, these things occur on a near-daily basis, part of the price of playing there.

In Cleveland there is no such price. Maybe because so little is ever expected, opinions aren’t as harsh. The Indians took it as a rallying point, though, and in the clubhouse after they clinched a playoff spot, players chanted “[Expletive] Paul Hoynes. [Expletive] Paul Hoynes.”

The dutiful beat writer, 33 years on the job, was suddenly the story himself. He couldn’t believe it. This was the last thing he wanted.

A fan on Twitter made him a bet: If the Indians didn’t get knocked out of the playoffs early, if they showed the resolve that, indeed, they would, and if, against all odds and injuries, they made the World Series, would Paul Hoynes offer a mea culpa of sorts by jumping in Lake Erie?

“Sure, yeah,” Hoynes said, “I’ll jump in the lake.”

So there Hoynes was Tuesday morning, at the dawn of the World Series, staring out at a lake that looked anything but welcoming. It was 9 a.m. on a cold, gray October day. A local TV station wanted to film it, but Hoynes wouldn’t allow them to come. This entire thing was enough of a circus, but he’d been wrong, he’d been called on it, and in Cleveland, you’ve got to answer for things sometimes.

So here on a sports day out of Cleveland’s wildest dreams, one that would end with that banner-raising courtesy of LeBron and a rollicking Indians victory, an old Catholic-educated Cleveland kid who never saw it coming did the penance he had to do.

“It was cold.”

*****

Joe Babin is 100 years old. He has multiple forms of proof. There’s a birth certificate, of course. There’s also a silver cup presented to his parents because he was the first baby ever born at the then-“new” Mt. Sinai Hospital on East 105th Street, which is particularly notably since the place closed two decades ago, Joe outliving it by 20 years and counting.

Finally, there is a video of Joe being honored on the “Today Show” for hitting the century mark, his headshot appearing on a jar of Smucker’s in the show’s famed product-promoted segment.

“I would have been fine if they just sent me some jelly,” Joe said.

Wait, Smucker’s doesn’t give the guys who live 100 years a free jar?

“Apparently not,” he noted, the first sign of his hysterical, tell-it-like-it-is personality.

When Babin was young they used to give kids a free ticket to the Indians at the end of the school year. The tickets were for bleacher seats but he didn’t care, old Dunn Field sat only 21,000 anyway. It was magical and he became a baseball fan. And a football fan. And eventually, later in life, even a basketball fan, LeBron James and all.

“I’m a Cleveland fan,” he notes, meaning the city. He went to Shaw High School and then Western Reserve College (now Case Western) for undergrad and law school before starting a construction supply business. He thought sports could market the city. The more the Cleveland teams won, he figured, the more people would move to Cleveland, which meant he could sell more windows and counter tops and cabinets.

It didn’t work out very well.

“The teams have been mostly terrible,” he said. “Cleveland, the city, is slipping. I’ve lived here all my life and I like it, but, unfortunately, the rest of the country doesn’t agree with me.”

It was still a great life, sports included, no matter the losses. “Being able to connect with my dad through these teams has been special,” said Joe’s son, Larry. Joe met his wife, Geraldine, at a 1936 Christmas Dance. He liked her so much he danced even though he said he didn’t know how to dance. He was 18. She was 15. This was problematic, even back then.

What did her parents say?

“I decided I wasn’t going ask them and find out,” he said. Geraldine had two older brothers, though, and they vouched for Joe. Seven years later the couple married. It lasted 71 years until Geraldine passed away in 2012.

“I think it was a pretty successful marriage,” Joe said.

Sports and symphony were his diversion. He worked a lot, not retiring until his 80th birthday. He liked being at the big games. He attended the 1948 World Series that the Indians won and the 1954 Series that they lost. He brought Larry to the 1964 NFL championship that the Browns won, the last title the city captured until the Cavs last spring. Larry returned the favor by taking him to the 1995 World Series, but the Indians lost that, too. Just when he got into basketball, LeBron left for Miami.

“People gave him a hard time for that, but he can make his money how he wants,” Joe said.

Then LeBron came back and the idea that Joe Babin might see another championship in his lifetime became a possibility. He might outlive the dysfunction? Well, there he and Larry were last Father’s Day, watching the Cavs beat Golden State on the television in Joe’s eastside apartment.

“I was crying, it meant so much to sit there next to my dad as they won,” Larry, 67, said.

“He’s such a romantic,” Joe said.

“Neither of us could stop crying,” Larry noted.

Joe shrugs. He changes the subject. He says he’s too old to go to a game now but was excited to watch the Indians, even if the game starts late and takes a long time. He planned on taking a nap to prepare. Larry was headed to the Cavaliers game, to see the long-awaited rings handed out.

The magnitude wasn’t lost on either of them. Just when Joe thought he’d seen it all … along comes a night when a championship party wasn’t the biggest show in town.

“Best day we’ve ever had,” Joe said. “There’s always next year. And next year we could be bums.”

*****

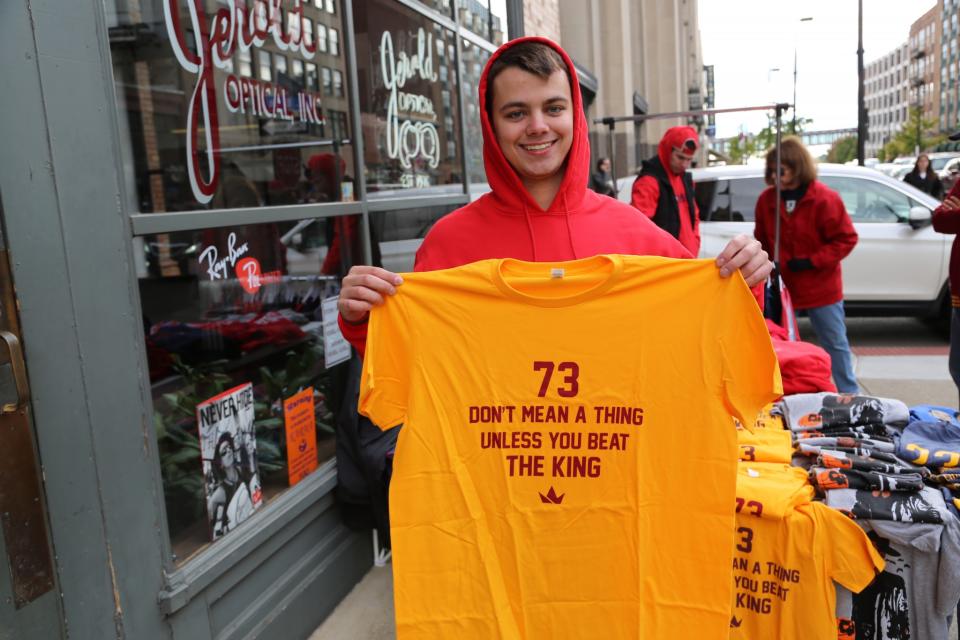

Joey Piscsalko is 20 years old, a student down at Kent State. His cousin, Billy Jelenic, is 22 and just graduated from Cleveland State. About a year ago they decided to start a business, Kingdom Apparel, coming up with sharp designs for T-shirts and sweatshirts based on Cleveland sports teams.

It’s late on Tuesday afternoon and the cousins are standing on Huron Road downtown as the streets continue to crowd with people. Thousands lack tickets to either event but have a desire to just be here, to be a part of it somehow. Piscsalko and Jelenic have a couple tables of merchandise set up in front of Jerold Optical Inc. a piece of prime real estate they secured by giving the owner and employees some free shirts – everyone loves young entrepreneurs and comp swag.

“It was the perfect time to start this business,” Jelenic noted.

Indeed. Their big seller, which put them on the map, was a T-shirt in Cavs wine and gold colors that read “23>73, Greatness is Defined in June.” That’s LeBron James’ number and the number of victories Golden State chalked up during the 2015-16 regular season. It was sent to market long before the two teams met in the Finals.

It was a huge hit, but it represented more than that. This was some bold talk, some big attitude. This was the kind of shirt a city that knows winning puts out. This was a couple of kids seeing Cleveland sports, maybe Cleveland itself, in a way that veteran reporters and centenarians wouldn’t or couldn’t or even shouldn’t.

Hell yeah we’re going to win. Hell yeah this is going to sell.

“We sold a few thousand,” Piscsalko said.

It paid for a hell of a lot of tuition. They put out more popular Cavs designs and made a particular killing during the million-person championship parade last June. They can’t afford to use NBA or MLB licensing, so as Jelenic noted, “you have to toy with the system.”

No trademarked logos or phrases are used, but people love it anyway. If anything, these two represent the new Cleveland, the one that isn’t reliant on shipping iron ore across the lake, the one that features young businessmen and women taking a chance in the city, starting businesses and eventually filling up once-abandoned downtown factories and warehouses that have been renovated into trendy lofts and condos. An estimated 10,000 new residents have moved downtown in recent years.

They are sitting on a new, potential big design, too. In August, the Indians won a game on a walk-off inside-the-park home run by Tyler Naquin that perfectly represented the pluck and potential of this team. To celebrate, Naquin held his hand aloft with his index and pinkie fingers extended.

A friend of the cousins noted it looked like a “W,” so what if they put that hand symbol before the word “Indians” (which they can’t use) to make the sort-of word “Windians” (which they can use).

(That no one thought to call the Indians the “Windians” prior to 2016 sort of says it all, of course.)

The design sold quickly. The cousins are very active on social media and this week connected on Twitter with the country group that will sing the national anthem on Wednesday. They were supposed to get them some Windian shirts and are hoping they will wear them on national television.

If so … well, they just shake their head at the sales possibilities.

Soon Piscsalko needed to attend to another push of customers. He had class Wednesday back at Kent, but right now, on Huron Road, he was all about business. Jelenic, meanwhile, had planned on looking for a job after graduating, at least until the booming apparel company became his full-time gig.

Just a guy making a living, selling championship shirts in Cleveland.

*****

Gloria Brach would love to move downtown into one of those new apartments high above. She knows empty nesters like her and her husband who have done it, eager to trade in the suburbs for the action of the city – the sports, the entertainment, the booming restaurant scene.

Unfortunately for Gloria, her husband Dennis Nida isn’t up for the move, at least not yet. Out in Newberry, Ohio, east of the city, they own an acre and a half of land and a sweet John Deere zero-turn mower. You don’t just give that up. The day might be coming, though.

The couple is sitting in the small plaza between Quicken Loans Arena, home of the Cavs, and Progressive Field, home of the Indians. This is Ground Zero for Cleveland joy – later thousands will fill it to watch each team on giant television screens. The couple, though, has Cavaliers season tickets, are wearing team garb and can’t wait to see the banner get raised in a few hours. They have time to kill after a nice dinner over at Mabel’s on trendy 4th Street. They attend every home game, playoffs included, grabbing dinner before the action.

“With LeBron, I feel like if I don’t come I might miss something,” Gloria said.

These are not what any sociologist or urban planner could predict would become passionate denizens of a once-depressed city center. Yet here they are, a white middle-aged couple from the far suburbs sold on the pace of city life via the NBA. Eight years ago, caught up in the excitement of LeBron, they got season tickets and began trekking into town, 45 minutes to an hour, all fall, winter and spring.

Now they know every spot here, especially anything run by Zack Bruell, the city’s patron saint of restaurateurs. They appreciate Cavs owner Dan Gilbert not just for finally building a winner, but also for investing in the city. Everything has changed. It’s wild, the crowd walking by stirring everything up. That’s the fun part.

Here comes Angie Brown, for example, who long ago bailed on these tough Ohio winters and moved to Maui. When the Cavs won in June, however, she cried so many tears of joy her husband worried the cops would come and arrest him. So she couldn’t miss Tuesday. She flew back to be with her still-Ohio-dwelling bothers, John and Ed, and bask in it all despite not having tickets. The only downer was the fact Ed was somehow a damn Cubs fan.

How’d you become a Chicago fan?

“He hit his head really hard,” John said.

“He asked me the question,” Ed said with a laugh. “I was a second baseman growing up and was a fan of Ryne Sandberg back in the 1980s.”

“Actually he’s adopted,” Angie joked, cutting him off.

Everyone laughed. It was this kind of liveliness that convinced Gloria and Dennis to keep their season tickets even when LeBron left for Miami in 2010. For four years they kept coming even as the Cavs lost and lost. Gloria admits she almost got rid of the tickets two seasons ago.

“It at least got us out of the house,” Gloria said. “We came this close, though.”

“Even closer,” Dennis said.

They didn’t. Then word began spreading that LeBron might come back. The Plain Dealer and 92.3 the Fan was saying it was possible, but Gloria refused to believe it, figuring getting her hopes up was just a guarantee for heartbreak.

Then one July day Dennis, who was driving home from work, called her on the phone and told her to turn on the radio. She was in the kitchen. She flipped it on and the hosts were reading LeBron’s “I’m coming home” letter from SI.com. It was true. He was back.

“I just cried,” Gloria said. “I couldn’t stop crying. I was sitting at home crying.”

A couple seasons later, and here they were, on a lovely autumn day waiting for the championship celebration with a championship series set for the joint next door. The plaza was filling up. The restaurants and bars were long ago packed – from the upscale Lola to the blue-collar Ontario Street to the trendy upstairs deck of Red.

Parking was going for $100. A hundred bucks? What a time in Cleveland. Money was practically raining from the sky.

“It’d be great to live down here,” Gloria said. Dennis couldn’t argue with that.

*****

With waves of cheers raining down upon the Quicken Loans court, LeBron James slipped the 2016 NBA championship ring onto his finger. James was raised in nearby Akron but he didn’t root for Cleveland teams. He liked the Chicago Bulls and the Dallas Cowboys and the New York Yankees. Winners. Champions.

“As a kid growing up, I needed inspiration to get out of the situation I was in,” he said of being raised by a single mom under economic stress. “Those are winning franchises. I liked them because they gave me hope of being a winner.”

Now a kid in Akron or Cleveland or anywhere else can be a fan. And not just the Cavs. “I definitely support what the Indians are doing right now,” James noted.

LeBron remains the King of Cleveland, or all of Northeast Ohio. Some fans wanted him to take a few minutes off from the Cavs game, ride in a golf cart through a tunnel between the stadiums, run out in full uniform and throw out the ceremonial first pitch for the Indians before returning to beat the New York Knicks.

That wasn’t going to happen (although the Cavs did win big, 117-88). That didn’t mean the kid who once shunned this place because it was so hapless didn’t understand the moment at hand. They handed LeBron the microphone and he offered a simple reminder.

“Hard work pays off,” he said. “… from this building to the one next door.”

The crowd roared and roared on this impossible night, for this impossible reversal of fortune. Cleveland? Forever-losing Cleveland? Cleveland hopes now. Cleveland believes now. Cold Lake Erie has bought the winds of change.

Cleveland wins. Cleveland booms.

“Cleveland against everybody,” LeBron announced.

Cleveland cheered some more.