How NCAA rule changes have made college basketball as 'watchable' as ever

The 2012-13 college basketball season was “ugly.” And those aren’t my words. They’re Rick Pitino’s. National championship winning coach Rick Pitino’s.

Louisville’s 2013 title was well deserved and Wichita State’s Final Four run memorable, but the season was forgettable. Our eyes told us that. So did the numbers. Division I teams scored the fewest points per contest since the introduction of the shot clock. And games were slower than ever; they featured, on average, fewer than 66 possessions for the first time since Ken Pomeroy started collecting data in 2001-02.

Even Pitino, six months after confetti fell, looked back on the year with derision. “Last season was terrible,” he said.

When the NCAA men’s basketball rules committee convened that offseason, the directive was clear: Fix a game that an increasing number of fans and media were labeling “unwatchable,” and do so by facilitating more offense.

“I think people don’t realize that there were layers of reasons why defense had become dominant,” says Belmont coach Rick Byrd, who was on the rules committee at the time and would later become its chairman. “One of them is just the ability we have to scout one another these days. Plus, the percentage of coaches who valued the defensive side of the game over the offensive side, and therefore recruited in that way, has grown.”

But there was another glaring issue, and one that, given other facts and figures, told a damning tale: Teams were called for just 17.68 fouls per game, an all-time low, and representative of a second-straight significant decrease in whistles.

“I think officiating, incrementally, they allowed more and more illegal defensive play,” Byrd continues. “So there’s a lot thrown into the mixer there that created the downswing in scoring.”

Something had to change.

And it did.

Four years and two major sets of rule amendments later, scoring is back up, and college basketball is as “watchable” as ever. Our eyes tell us that. So do prominent writers.

So do the numbers.

College basketball teams aren’t just scoring more. They’re scoring more efficiently. And, crucially, they’re doing so while shooting fewer free throws, a clear indication that the game has changed for the better.

***

The first attempt at reform came in 2013. The rules committee, after discussions with the National Association of Basketball Coaches and others, introduced a package that has been commonly referred to as the freedom of movement rules. It cracked down on hand-checking, arm bars and other physical impediments to offense, and tweaked the block/charge rule.

It was also fleeting and unsuccessful.

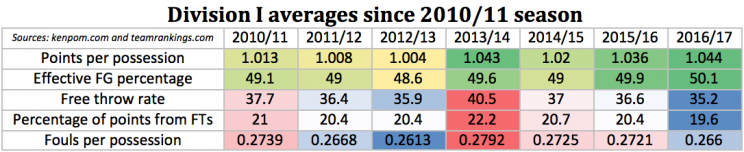

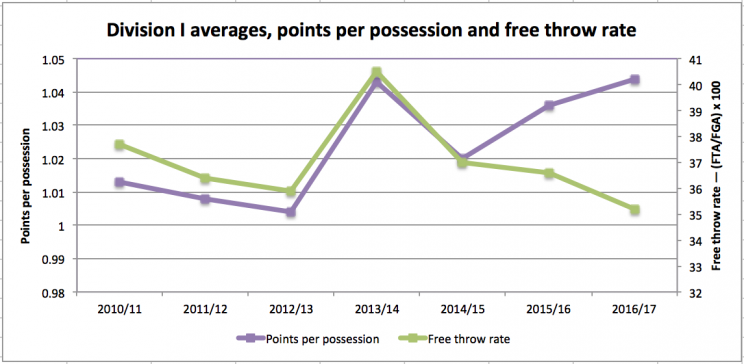

Scoring soared, but the game wasn’t any more watchable, because fouls did too. Points per possession across Division I rose to 1.043, up from 1.004 the previous season. However, the increase in division-wide shooting percentages — 49.6 in 2013-14, up from 48.6 — wasn’t nearly as significant as the increase in fouls — 0.279 per possession, up from 0.261, per teamrankings.com data. The average free throw rate was 40.5, nearly three percentage points above the second-highest rate since 2001-02. And the percentage of points scored on free throws was 22.2, also the highest since Ken Pomeroy started tracking. (See Table 1)

And coaches, of course, complained. “They want an 86-82 game. Do they want to watch that garbage for four-and-a-half hours?” moaned West Virginia’s Bob Huggins. “Do they want to do that by shooting 70 free throws?”

Kansas’s Bill Self concurred: “The best way to increase scoring and make the game better is to create situations to get more shots. More free throws doesn’t make the game better.”

Referees undoubtedly heard the grousing, and they caved before coaches and players did.

“We went forward [at first],” says Akron coach Keith Dambrot, the current chairman of the rules committee. “And then by mid-season or a little past mid-season, [officiating] was back to how it used to be.”

Byrd saw a similar arc. “It was really tight to begin with. People were shooting 60 free throws in a game,” he says. “And then it wasn’t nearly that way. And a lot of that was the officials backing off.”

The following season, scoring slid back down to 1.020 points per possession. Fouls remained higher than the average over the past decade, at 0.273 per possession. And the rules committee, once again, had a problem to address.

***

“I could have done without the shot clock change,” says Byrd, the chairman of the rules committee when it assembled in 2015. “That was the thing that everybody talked about … I felt all along that it was going to have very little effect on the game.”

And he wasn’t alone. Many coaches agreed that while the move from a 35-second shot clock to 30 garnered the most attention, another facet of a robust set of 2015 rule changes was absolutely imperative.

In fact, it wasn’t a rule change at all. It was a reinvigorated second attempt at implementing the points of emphasis from 2013, and it has been every bit as successful as the first attempt was unsuccessful.

The pace of the game has increased. Possessions per game jumped to 69.0 in 2015-16, up from 64.8 in 2014-15, and have increased again this year, to 69.4. Naturally, scoring has increased too, to 71.5 points per 40 minutes last year and to 72.5 per 40 so far this year.

But the scoring spike isn’t entirely explained by pace. Teams aren’t just playing more offense. They’re playing better offense. Some coaches actually believed five fewer seconds would harm offensive efficiency. It hasn’t. Or if it has, the elimination of handsy, physical defense has more than made up for any negative effects.

Points per possession increased last year, and has again this year. So has effective field goal percentage. And while the 2016-17 data sample is far from complete, efficiency has tended to rise — or at least plateau, but not fall — in conference play in previous years. If that trend continues, 2016-17 will feature more points per possession than the foul-juiced year of 2013-14. Amazingly, and most importantly, it will do so with the lowest free throw rate (a stat that tends to decrease as the season wears on) in at least 15 years:

Coaches grumbled again early in the 2015-16 season. “Why do you want the best players on the bench?” Michigan State’s Tom Izzo questioned. “Why do we want a free throw contest?”

“We’re taking the flow of the game away,” Providence’s Ed Cooley echoed. “I don’t agree with it.”

The complaints were to be expected, just as they were in 2013.

“What generally happens when you have a new rule, the first couple months everybody gets all worried about it; it’s overcalled,” says Georgia State coach Ron Hunter, who was the president of the NABC in 2015. “Then it evens itself out.”

In 2013-14 and 2014-15, officials reverted to old ways before coaches and players developed new ones, and thus the natural correction wasn’t all that even. It was skewed toward the status quo. This time, aware of prior pitfalls, the commitment from officials was more steadfast. That commitment sent a message to coaches and players: You have to change, because this time, we won’t.

“We did a much better job than in the past of publicizing what we were trying to do, and making people aware that it’s going to happen,” Byrd says. “There’s going to be a period where you gotta adjust, but we think once some adjustments are made by all the people involved, that scoring will be up, and it won’t be because of fouls.”

Coaches credit J.D. Collins, who was appointed NCAA coordinator of officiating in 2015, with ensuring games are refereed the same in March as they are in November, and the same on the East Coast as they are on the West Coast. They also credit conference officiating coordinators, and their communication with Collins and one another, with helping create consistency across games and leagues.

“It’s the consistency of the fouls,” Hunter stresses, that is pivotal. “It’s not what’s being missed, it’s the consistency. It’s not about the number that you’re calling, it’s the consistency. A foul is a foul is a foul. If we go by that principle, coaches know it, players know it, and officials call it.”

As Dambrot says, there will always be “slippage.” It’s impossible to adjudicate the game perfectly. There are still problem areas, including illegal physical play in the post that goes uncalled, and still room for improvement.

There will also be discussions of further changes. Dambrot, the current rules committee chairman, anticipates serious talk of widening the lane and moving the three-point line back in the near future. Hunter wants to go to quarters rather than halves so that the bonus resets three times rather than once, and he’s not the only one.

But most coaches — even traditionalists or purists like Byrd, who jokes that if it were up to him, he might go back to James Naismith’s original rules — are somewhere between pleased with and ecstatic about the effects of the 2015 rule changes on the on-court product. And how could they not be?

Fouls are down. Scoring is up. Pace is up. Entertainment, therefore, has returned.

“Remember, we’re in the entertainment business,” Hunter says. And because coaches recognized that two years ago, business is thriving.