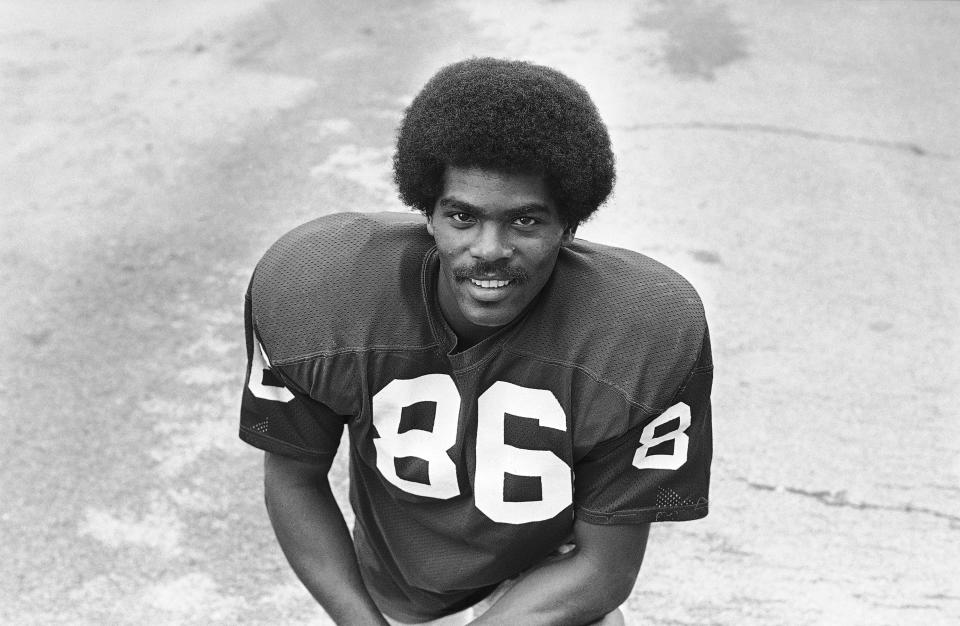

Marlin Briscoe became the NFL's first black starting quarterback 50 years ago this week

1968 was a bittersweet year for civil rights. It saw the passage of the Fair Housing Act, and gave us the iconic image of John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising their black-glove clad fists on the medal stand at the Summer Olympics.

But it was also the year both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated, two men who wanted to carry the country to equality for all Americans.

That same year, on Oct. 6, 1968, there was a historic first in the NFL that has largely become forgotten in history: Marlin Briscoe became the first African-American to start a game at quarterback, doing so for the Denver Broncos against the Cincinnati Bengals.

Briscoe, just 5-foot-10 but known as “The Magician” for his incredible athleticism, was a star at Omaha University at quarterback. The Broncos drafted him in the 14th round in 1968, and he was at the bottom of a long depth chart at the position – and asked to play receiver instead.

The prevailing belief then – one that persists in the minds of some 50 years later – was that black players weren’t smart enough to be quarterbacks at the pro level, not good leaders.

Briscoe did get some snaps under center in practice, but they were limited. He knew whatever snaps he got at quarterback, he had to be perfect.

“I made sure that all of my passes were completions with zip on the ball,” Briscoe told the Associated Press recently. “When it came to the long bomb, I’d wait till the receiver would get damn near out of sight. They couldn’t believe a kid this small could throw the ball that far.”

In the third game of the season, Briscoe got his first chance, playing at quarterback and scoring a fourth-quarter touchdown against the Patriots.

The next week, he got the start, and the Broncos got their first win of the season, 10-7 against Cincinnati. Briscoe started the final four games of that season too.

“It just seemed poetic justice, so to speak, that the color barrier be broken that year at that position,” Briscoe said. “For some reason, I was ordained to be the litmus test for that. I think I did a good job.”

But he would never play quarterback again.

Another quarterback gets the chance Briscoe didn’t

As a student at Grambling State, James “Shack” Harris made frequent visits to the library to track the statistics and success of three players: Briscoe at Omaha, Jimmy Raye at Michigan State, and Eldridge Dickey at Tennessee State. All three were quarterbacks. All three were black.

But only Briscoe would ever play quarterback for an AFL or NFL team.

Harris was a senior in 1968 when Dickey became the first black quarterback selected in the first round when he was drafted by Oakland. In Louisiana, Harris, who led the Tigers to at least a share of the SWAC title for each of his four years as the team’s starter, saw it as a hopeful sign.

“When Dickey got drafted, I thought that meant I would get a chance to play quarterback, so I was happy,” Harris said on Friday. “Then they moved him [to receiver] and that deflated me. Marlin was moved to receiver, Jimmy Raye was moved to defensive back, so it didn’t look so good.

“Then the quarterback in Denver got hurt and Marlin played, and he played well, and it looked like there was hope for me again.”

Briscoe had played well in his opportunities in 1968, with 1,589 yards and 14 touchdowns passing plus 308 yards and three touchdowns rushing; he was runner-up for AFL rookie of the year.

But as the 1969 season approached, Briscoe wasn’t given a chance to compete for the quarterback job, let alone win it. He says he was never given an explanation. So he asked for his release.

Harris, meanwhile, was going through his own trials.

Over his four years at Grambling State under the tutelage of Eddie Robinson, he’d spent as much time as possible preparing to be an NFL quarterback, and Robinson told him it was possible. The buzz was that Harris would be a high-round pick, but he let it be known that he would play only quarterback.

“I decided my best opportunity was to play quarterback,” Harris said. “[Teams] called me and asked me to switch positions, and I said no. I kept my word, and they kept their word: They didn’t draft me that high.”

Taken by the Buffalo Bills in the eighth round, Harris wanted to walk away from the sport. Robinson persuaded him to report to the Bills.

After a brief stint in Canada, Briscoe also was picked up by Buffalo.

“I felt when he got there he was bitter, and rightly so,” Harris said. “He played a good season, and now all of a sudden you don’t get an opportunity to play. Marlin walked in and I realized that could be me. I thought any day I could get cut, because I saw Marlin play [and it had happened to him].

“We became roommates and we talked and we shared some things that only the two of us understood because everybody else on our team was competing at a job where pretty much the best player wins; it was open competition. But for us, we needed a prayer. We needed an opportunity.”

Briscoe didn’t get another opportunity, not at quarterback. Underscoring his athleticism, he became a Pro Bowl receiver with the Bills, with 57 catches for 1,036 yards and eight touchdowns in 1970. He went from the Bills to Miami, spending three years with the Dolphins, including the undefeated, Super Bowl-winning 1972 season. After splitting the 1975 season between the Lions and Chargers, Briscoe finished his career with the Patriots in 1976.

His former teammate and roommate, however, got the opportunity Briscoe never did: Harris got one start as a rookie in 1969, but saw mostly backup snaps for the next three years.

In 1974, by now with the Los Angeles Rams, Harris started the final 10 games of the season.

The Rams were 3-2 when Harris took over, and finished 10-4 and as NFC West champions, with Harris chosen for the Pro Bowl. Los Angeles beat Washington in the divisional round, and lost to the Vikings in the conference championship.

Harris started 13 of the Rams’ games in 1975, but spent the 1976-78 seasons as a spot starter with the Rams and Chargers. His final season was 1979.

‘How far we had to go and how far we’ve come’

A direct beneficiary of Briscoe and Harris, Doug Williams made a new kind of history early in 1988, when he led Washington to a dominant win in Super Bowl XXII, the first black quarterback to lead his team to a Super Bowl title.

“I didn’t know who [Briscoe] was until I was older,” Williams said this week. “I knew he had played, but didn’t know the impact of what he’d done. I just talked to him about two weeks ago and listening to him and things he said and things he went through as a quarterback, it wasn’t surprising during that time.

“To put things in perspective, young black quarterbacks couldn’t understand what Marlin went through. He had an everlasting [impression] on me, to think how good I had it compared to him and James Harris.”

Williams, who like Harris also was an Eddie Robinson disciple from Grambling State, was the 17th overall pick in the 1978 draft, taken by the Buccaneers. Just a decade after Briscoe made his debut, not all fans were ready to have a man like Williams lead their team.

“I went through mine, that’s why I know Marlin and James had to be a lot tougher than me. I got letters, I got a lot of things when I was with Tampa in ‘78,” Williams said. “It got to the point if I got a letter with no return address, I wouldn’t even open it. I understood it, but it’s one of those situations: you have to keep going.

“But if I had known, I would have kept the letters to see how far we had to go and how far we’ve come.”

Both Williams and Harris talk about how talented Briscoe was. Briscoe’s style of play was a precursor to some of the game’s current and more recent stars.

“They called him ‘The Magician’ – the Magic Man,” Williams said. “You see the Michael Vicks, [Patrick] Mahomes – the trouble he was able to get out of and make plays, that’s who Marlin Briscoe was.”

Harris said Russell Wilson plays like Briscoe.

“The word was we weren’t smart enough, we couldn’t lead,” Harris said of himself and other black QBs. “In order for him to play, during that time for anyone to play, you had to know the game. He knew the game. He understood the game.”

Having seen Briscoe, and Dickey and Raye, Harris knows they could have been successful quarterbacks, had they not been switched to other positions.

“There were outstanding black quarterbacks that I’d seen,” Harris said. “And once I got into the league, I realized even more [they could have played at a high level]. I always feel really bad about those guys that came before me who could really play that didn’t get a chance just because they were black.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Tom Brady throws 500th career TD in win vs. Colts

• LeBron sports Kaepernick shirt during NBA preseason

• Tim Brown: Braves understanding October’s cruelty

• Dan Wetzel: Underbelly of college hoops is being exposed