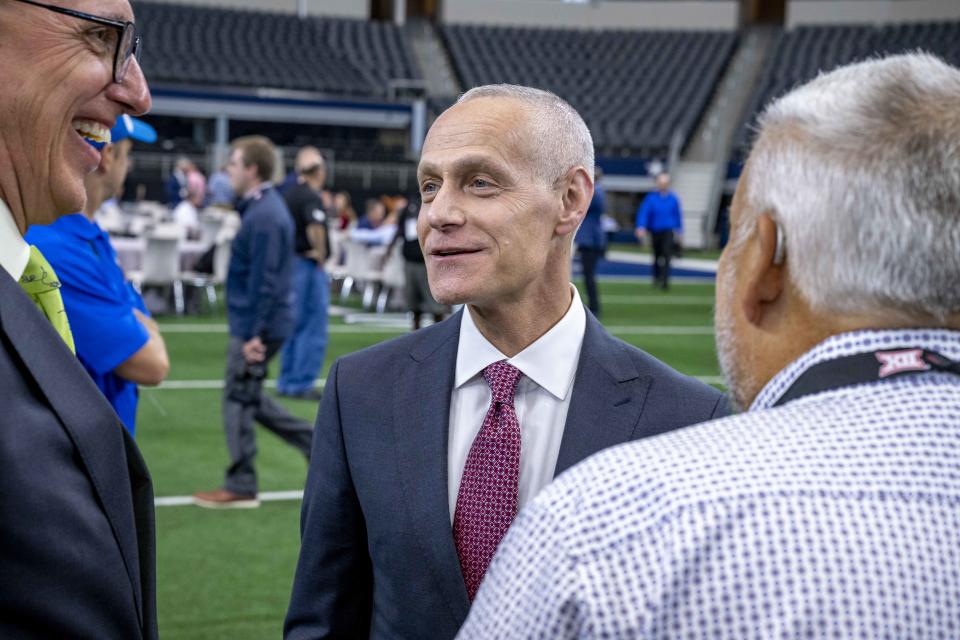

George Kliavkoff did not have a good job interview with the Pac-12 CEO Group

We don’t know exactly what was said in the room when the Pac-12 CEO Group interviewed George Kliavkoff for the job of Pac-12 commissioner a few years ago.

We don’t have a transcript of the dialogue between the Pac-12’s school chancellors and presidents and the people they interviewed to replace Larry Scott.

Yet, as the Pac-12 teeters on the brink of collapse, we can be very confident in saying this much: The job interview process did not go well. It wasn’t handled well. The Pac-12 CEO Group didn’t understand what kind of leader it needed, and George Kliavkoff didn’t fully grasp the dimensions of his situation.

People reading this might say, “But wait: George Kliavkoff took over the Pac-12 before USC and UCLA left for the Big Ten. No one could have anticipated they would leave.”

Narrowly, that might be true. However, the Pac-12 had suffered under Larry Scott. It was not in an advantageous position. Everyone knew it needed a better media rights deal. That’s why Kliavkoff was hired, regardless of whether USC stayed or left.

If you realize that Kliavkoff was supposed to be a dealmaker who got things done, we can look at the present moment and plainly say he hasn’t lived up to that standard. In this regard, he failed to grasp what was needed in the moment.

Let’s talk more about this as “Pac-12 death watch” intensifies:

LARRY SCOTT'S HISTORY

As bad as Larry Scott was, and as responsible as he is for the Pac-12’s problems, we do have to remember that in 2011, he pitched the Pac-16 proposal in which Texas, Oklahoma, Texas Tech, and Oklahoma State joined the Pac-12.

It was the presidents who shot down that proposal. The commissioner was bold; the presidents were fearful. That memory looms large 12 years later, as the Pac-12 stands on the verge of extinction.

ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

The Pac-12 CEO Group asked questions of George Kliavkoff, but Kliavkoff needed to ask questions to the Pac-12 CEO Group in a job interview as well.

The biggest question Kliavkoff needed to put to the CEOs was this: If we get into a crisis, am I going to be fully empowered to act, or will you put a restraint on me? Am I going to be able to act in the best interests of the conference, or do you basically want someone who will follow a plan or blueprint no matter what the consequences might be?

Given that a media rights deal had seemingly been arrived at much earlier in this process — in the late winter or early spring of 2023 — only for the presidents to reject it and insist on continued negotiations, it certainly seems Kliavkoff was not fully empowered to act. He was operating under the constraints imposed by the Pac-12 CEO Group. To that extent, he didn’t fully grasp the job … but there’s a little more to the story than that point alone.

MARRIED TO THE PLAN

Kliavkoff had a plan for how the Pac-12 was going to survive: First, the grant of rights would be signed. Then the media rights deal would be done. Third, expansion would be considered.

In a “peacetime” context, this seemed reasonable enough. Get the binding agreement with lasting significance signed first. Then lock the media deal in place. In a world without extreme stress or pressure, with schools not about to move, that process seemed logical. The problem wasn’t the plan itself, though. It was Kliavkoff’s refusal to budge from it when real-time events changed and the calculus of the situation changed along with it.

SAN DIEGO STATE LETTER ON JUNE 13

When San Diego State sent that June 13 letter to the Mountain West, the Aztecs were basically waving a huge sign which said, “Take Me!” The Aztecs were begging the Pac-12 to take them. Remember: SDSU leaving the Mountain West by June 30 would have created a $16.5 million exit penalty fee. The Pac-12 could reasonably cover that. Failure to admit SDSU by June 30 would more than double the penalty fee to $34 million.

The Pac-12 vetted San Diego State. The Pac-12 claimed to want San Diego State. The media rights deal would increase in value if San Diego State was part of the conference — not by an astronomical amount, but certainly by a few million dollars. Getting a new member at a relatively affordable cost was a beyond-obvious move for the Pac-12 to make. This point simply cannot be debated. It’s a “two plus two equals four” or “the sky is blue” kind of statement.

MORE ABOUT SAN DIEGO STATE

The other key point to make about San Diego State in light of Colorado’s departure is the Aztecs would have provided insurance for the possibility of CU leaving.

If Colorado left, San Diego State was the replacement 10th school for Colorado. Having 10 schools would have made it a lot harder for the Arizona schools to leave. At nine schools, however — with San Diego State carrying a bigger price tag (the larger exit fee) — it is a lot harder for the schools to stay and trust that the league will survive. The Pac-12 is short-handed with Colorado gone and San Diego State not on board. Not having that piece of flight-risk insurance really mattered.

SAN DIEGO STATE AND SMU

If San Diego State had been on-boarded in late June, SMU could have quickly been added right after the Aztecs were brought into the Pac-12. The conference would have had 12 teams with a foot in Southern California (Aztecs) and Dallas (Mustangs). Under this scenario, Colorado and the Arizona schools would have had a much harder time leaving. Under this scenario, media rights value would have increased. How much the value would have increased is a separate question. The claim that the value would increase? That is incontestable.

PROCESS VERSUS RESULTS

Process matters. Sloppy process often leads to bad results. To this extent, one can understand why any person or group emphasizes sticking to the plan and the right procedure. Yet, life is messy and complicated. When real-time events — such as San Diego State sending that June 13 letter to the Mountain West — create urgent situations, a group and its leader must act.

George Kliavkoff was so intent on following the plan — grant of rights first, media deal second, expansion third — that when the need to add San Diego State (for sure) and probably SMU right after that emerged, he wouldn’t act. He stuck with the plan, the process. He wasn’t focused on the end result. He didn’t seem to realize that getting schools in the door was itself a way to increase the odds of Pac-12 survival, which was always supposed to be the ultimate goal of media rights negotiations.

CIRCLING BACK

This is where we go back to the point that if Kliavkoff did not insist — in his job interview a few years ago — that he needed to be fully empowered to act in crisis situations, he didn’t fully understand the job.

If Kliavkoff’s apparent adherence to his plan — grant of rights first, media rights deal second, expansion third — was actually a case of the Pac-12 CEO Group forcing him to adhere to that plan (when Kliavkoff privately wanted to bring San Diego State aboard in late June), then the CEOs bear even more responsibility for this mess than they already do. However, it also means Kliavkoff failed to secure an agreement from the CEOs — when he took the job — that he needed to be a fully-empowered commissioner.

Either way, the CEOs and Kliavkoff both showed an incomplete and flawed understanding of what was at stake.

BIG 12 COMPARISON

The Big 12 did not approach this situation the way the Pac-12 did. The additions of BYU, UCF, Cincinnati and Houston fortified and expanded the league and provided a buffer against possible defections. Media markets — particularly Houston — were added to the equation. That helped fetch a price point that was surprisingly good, considering Texas and Oklahoma were leaving.

BIG 12 HAD MORE TO OFFER

The Big 12 faced the problem of Oklahoma and Texas leaving for the SEC. The Pac-12 faced the problem of USC and UCLA leaving for the Big Ten. It’s not as though the Big 12 was in a structurally better position than the Pac-12. Both conferences faced existential concerns. The Big 12 clearly handled its situation better, and the willingness to expand is a clear point of differentiation. The Big 12 was willing to pull the trigger and add teams. The Pac-12 was not. That made a huge difference.

BLAME GAME

Is it Kliavkoff or the Pac-12 CEOs who are most to blame? They are both hugely and centrally responsible, but if you really had to choose, which side bears more blame for this catastrophe? If we’re being fair and accurate, it really is a situation in which both sides bear equal blame: The CEOs for not empowering their commissioner enough, and Kliavkoff for not understanding how important it was and is to be a decisive presence who valued action over board meetings and results over process.

This was about survival, not norms or procedures. This was about getting stuff done, not about using the right method. No one in the Pac-12 seems to have understood that. The consequences have been felt throughout the conference and college football.