Who was missing from the Democratic debate?

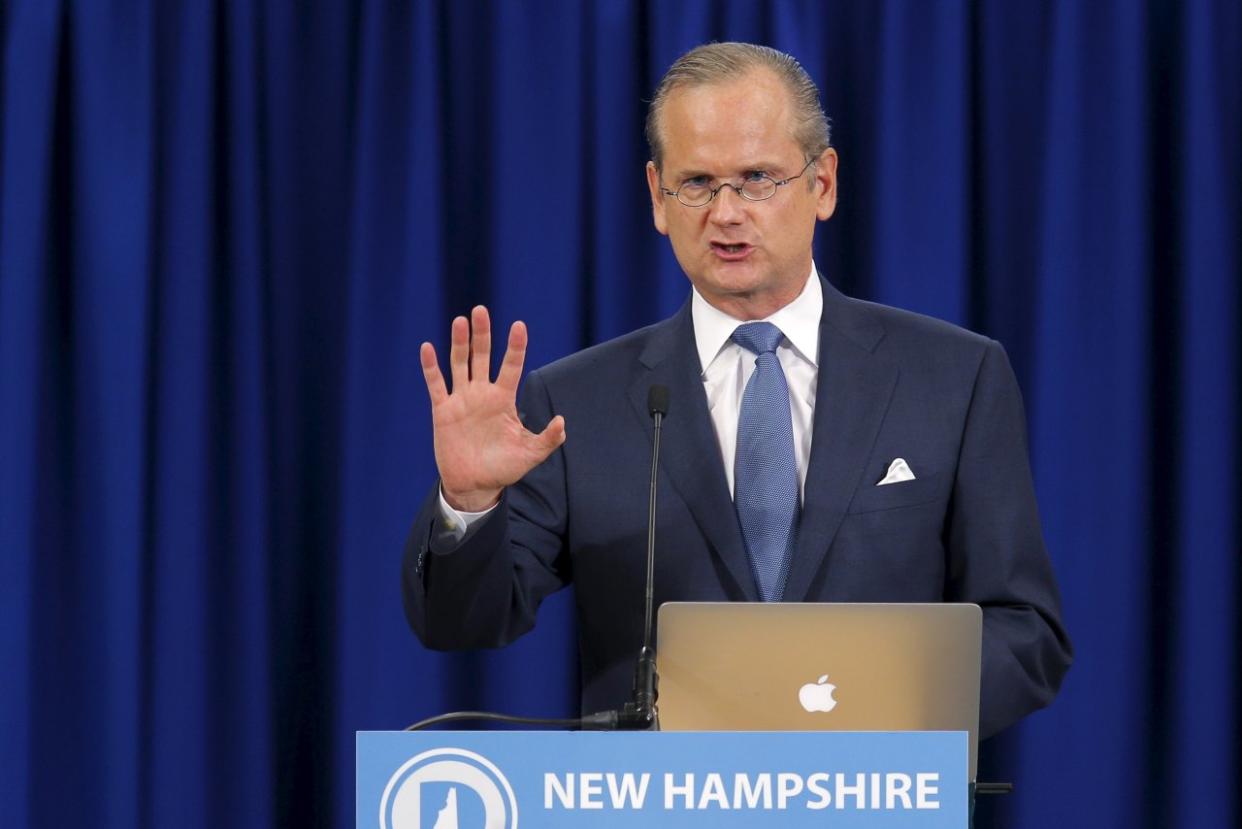

U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Lawrence Lessig speaks at the New Hampshire Democratic Party State Convention on Sept. 19, 2015. (Photo: Brian Snyder/Reuters)

There was no need for a second-string debate in Las Vegas on Tuesday night. With less than half the number of candidates as the GOP, the entire Democratic presidential field fit comfortably on one stage. There was even enough room to save a spot for Vice President Joe Biden, though he didn’t make a game-time decision to enter the race. Still, not every declared Democratic candidate was able to partake in the party’s first primary debate.

Despite boasting a bit more name recognition than Jim Webb and Lincoln Chafee, both of whom joined Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley on stage in Las Vegas on Tuesday night, Lawrence Lessig was the only declared Democratic candidate who wasn’t invited.

The Harvard law professor threw his hat in the ring in early September after raising $1 million in under a month. But he failed to meet the Democratic National Committee’s newly created criteria for debate participation: an average of 1 percent support in three major polls since Aug. 1. The Bloomberg Editorial Board urged DNC Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz to let Lessig into the ring with the other Democrats, as did the 2,976 signatories of a MoveOn.org petition. But come Tuesday, he was still on the sidelines. According to Lessig, he never had a chance.

“Of the last 10 major polls, only three mentioned my candidacy,” Lessig wrote in an op-ed for Politico earlier this month.

Slideshow: First Democratic debate >>>

“One poll recently put me at 1 percent (for comparison, candidates O’Malley, Webb and Chafee, who each were welcomed at the debates, were all currently polling at 0.7 percent or less, according to Real Clear Politics),” he wrote. “Were I actually included on every poll, I would easily make the debates.”

Lessig argued that his absence from the polls was a reflection of the Democratic Party’s refusal to acknowledge his candidacy and has subsequently resulted in him being ignored by the media.

“This experience has led me to believe it’s not just the rules that discourage an outsider Democrat,” Lessig wrote of his exclusion from Tuesday night’s debate. “It’s also the party. And that resistance may tie quite directly to the message of my campaign — one that no politician so far has had the courage to say.”

The assertion of Lessig’s campaign is that American democracy is in desperate need of repair. And while similar refrains have been heard from candidates in both parties, Lessig is the only one who has centered his campaign around this single issue, arguing that any other kind of major policy reform — whether it’s involving immigration, health care or climate change — is impossible without first overhauling the country’s electoral system.

Lessig’s presidential platform is essentially a piece of legislation in progress: The Citizen Equality Act is a collection of proposed reforms that include redrawing districts for more evenly distributed representation, removing barriers to voting by implementing automatic voter registration and declaring Election Day a national holiday, and imposing tougher restrictions on political donors while simultaneously creating a voucher system to give all voters a chance to contribute to campaigns.

If elected, Lessig has promised to get the Citizen Equality Act passed and then promptly resign, allowing his vice president to become “president of a government that works.”

Lessig has been fiercely critical of his fellow Democrats’ ability, as career politicians, to get serious about campaign finance reform, and has praised GOP candidate Donald Trump for calling out his Republican opponents’ dependence on influential donors.

Like Trump, Lessig’s status as a political outsider puts him in the unique position to highlight flaws in the system by saying things other candidates can’t. Unlike Trump, however, Lessig can’t seem to get a word in.