This is why candidates stick around for one-person events in Iowa

Democratic presidential candidate and former Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley speaks in December in Iowa Falls, Iowa. (Photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

On Monday night, only one man showed up at a campaign event for third place Democratic presidential candidate Martin O’Malley in the tiny town of Tama, Iowa. O’Malley, the former governor of Maryland, still spent time talking with the man, and his campaign subsequently sent out a press release touting the “only-in-Iowa, one-on-one meeting.”

It was an extreme example of Iowa’s personal politics, but even candidates who are faring far better than O’Malley in the polls are focused on individual voters in the state. In an email to supporters Tuesday, Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton wrote that elections “can come down to the smallest of margins — like a handful of voters in an Iowa precinct.”

Indeed, thanks to its relatively complex caucus process and influential role as the first state to vote in the presidential election, Iowa forces White House hopefuls to engage in intense house-to-house fighting for the hearts of potential caucusgoers.

The two parties have different procedures, but a pair of experts who spoke to Yahoo News said the Iowa caucus could come down to a shockingly small number of votes for both the Republicans and Democrats.

“You can turn this with a few votes in every precinct,” said David Redlawsk, a Rutgers University professor who is also the director of the Eagleton Poll and has written a book about the Iowa caucus.

The delegates Iowa will ultimately send to each party’s convention are not necessarily awarded based on the caucus. However, the caucus results are the first real numbers in the presidential race, so the way candidates finish in Iowa can have an impact on who chooses to stay in the race and how voters pick in the primaries and caucuses that follow. And that initial Iowa result can come down to the wire.

“I think people would be surprised at how few individuals it takes to potentially shift the numbers,” said Redlawsk.

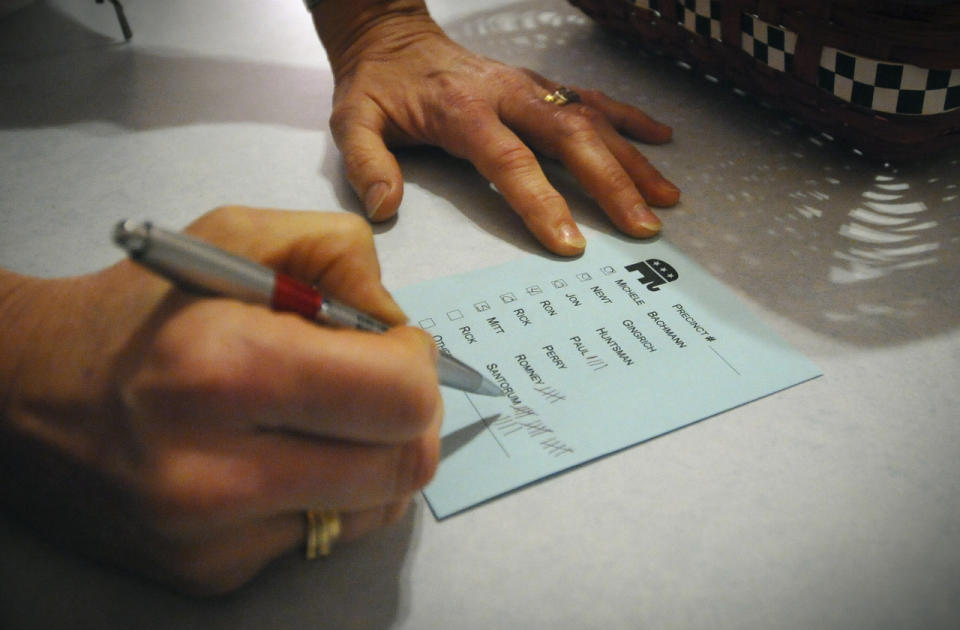

Votes are tallied during a caucus of precinct 42 near Smithland, Iowa, in 2012. (Photo: Dave Weaver/AP)

The total amount of voters participating in each party’s caucus is relatively small. Redlawsk noted the “largest Republican turnout ever” came in 2012 when slightly more than 120,000 people voted. The Democrats saw their biggest numbers in 2008 when President Barack Obama was making his historic run and about 225,000 people participated in the caucus.

“No one expects the Democrats to hit that number again,” Redlawsk said.

The process is relatively straightforward on the Republican side, where individual votes are counted. In recent years, candidates have won with only about 30,000 total votes.

But with a large field of at least 12 candidates this year, the number of votes necessary to win the caucus may be even smaller.

Tim Hagle, a political science professor at the University of Iowa who has written extensively about politics in the state, cited the typical turnout numbers to describe how this year’s race could have fewer people than usual backing the winner.

“You could have five or six candidates that are splitting that vote and, even if it’s something around that 120,000 … you could have somebody with well less than 30,000 votes that ends up being the winner,” Hagle explained.

To put that in perspective, 30,000 is slightly less than 1 percent of Iowa’s already smaller-than-average population.

Along with ensuring the Republican winner will only need the backing of a fraction of a percentage point of Iowa’s population, the large GOP field also means the margins between the candidates could be extremely tight. Only a handful of voters could separate each of the Republican hopefuls. Hagle pointed to 2012, when the difference between former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.), who won the caucus, and the second place finisher, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, came down to double digits.

“Last time around, Santorum and Romney were only separated by 34 votes and then [former Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas)] was not that far behind,” said Hagle.

The margins will prove important since first place might not be the only one to watch in the Republican caucus. For a candidate who beats expectations, even a third or fourth place finish might make an impact in the rest of the primary. Hagle said that a few candidates could survive the caucus, especially if they all finish close together.

Voters debate during a caucus of precinct 42 near Smithland, Iowa. (Photo: Dave Weaver/AP)

“What I usually tell folks is that the point of Iowa isn’t so much to select the person that’s going to be the nominee for either party, but to separate the contenders from the pretenders,” Hagle said. “We usually talk about three tickets out of Iowa, but with the number of Republicans this time, it could be a little bit higher … depending on how they’re grouped.”

The Democratic side of the caucus might come down to even smaller numbers, thanks to their more complex process.

In each of the 1,682 precincts around Iowa, Democrats meet at an appointed time and place where they gather in groups depending on whom they support. After a headcount, they determine whether any candidates fall below the viability threshold of backing from at least 15 percent of the voters. Those who do are removed from contention, and their supporters are courted by groups backing the remaining candidates. In the end, each precinct awards a specific number of delegates based on its population and participation in past statewide races.

“With the Democrats … they actually physically get up and walk around the room and get in their groups,” Hagle explained, adding, “There’s some negotiating kinds of stuff that goes on.”

Since their caucus system doesn’t rely on simply counting votes, the Democrats don’t actually release totals for each individual candidate. Still, with fewer than 200,000 people expected to participate and more than 1,600 precincts, that means there will be around 100 people at the average location. In rural areas, the number of people involved is even smaller.

“In rural counties, it takes a very small amount of people to win the delegate on the Democratic side,” said Redlawsk.

This virtually ensures there will be precincts where delegates are awarded to the Democratic hopefuls based on single and double digit differences in their support.

In the Republican race, with every one of the approximately 120,000 likely votes being potentially crucial, individual outreach could prove equally vital.

Hagle noted that even though the GOP process is less complex, voters still must arrive at a set location on time and stay for an extended period. Because of this, Hagle said Republican campaigns have to be in touch with their individual supporters and “reaching out to them every week between now and caucus day” in February.

“You’re looking at this small turnout,” said Hagle. “The ground game is going to be critical.”