The Bernie Revolution: What’s so appealing about a grumpy 74-year-old?

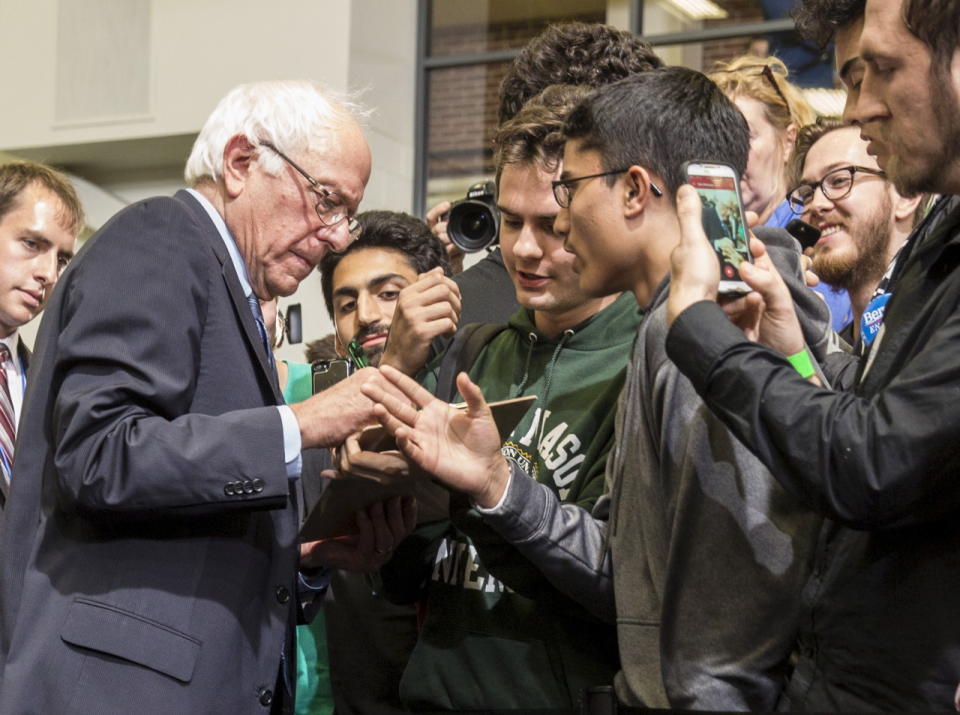

Bernie Sanders speaking at George Mason University in October. (Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

It’s a drizzly Wednesday evening in October and the presidential campaign has descended on a college campus in suburban Virginia. The line of students begins way out in the parking lot, a procession of flannel and hoodies and trendy rain boots winding up the stairs and through the doors of the campus rec center, snaking down polished hallways until reaching the gymnasium. Attendees scribble their names and email addresses on pledge cards and drop them in a box on the way in. Young volunteers in campaign T-shirts corral the unwieldy masses, and the late arrivals plead for a seat inside.

We’ve seen this hundreds of times before: The gymnasium filled to the rafters, the handwritten banners and the phalanx of TV cameras, the klieg lights aimed at center stage, the rock music blaring as the candidate makes his or her entrance. But the setting of tonight’s rally, George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., isn’t some hotbed of ivory tower liberalism on fire for the latest Democratic rock star. If anything, George Mason is known as a bastion of libertarianism and a magnet for major donations by right-leaning luminaries such as the billionaire industrialists Charles and David Koch. The headliner of tonight’s student town hall, the object of affection for all these college kids, isn’t quite whom you’d expect either: a rumpled, irascible democratic socialist from the state of Vermont named Bernie Sanders.

Take a look at him: Sen. Bernard Sanders, age 74, is not young, handsome or polished like Bill Clinton or Barack Obama were when they ran for president. He doesn’t care much for working rope lines or rah-rah chants. The closest thing he has to an official slogan is the legally required fine print on his website and campaign lit: “PAID FOR BY BERNIE 2016 (not the billionaires).”

His stump speeches steer clear of the typical campaign pabulum. No city-on-a-hill imagery. No spit-shined paeans to the “greatest country on earth.” Sanders prefers to rattle off one grim fact after another about the dire state of our union—2.2 million people incarcerated; $1 trillion in student debt; the vast gap between top 1 percent and everyone else. His transitions — “Now, there’s another issue I want to discuss” — send Ted Sorensen spinning in his grave. If Obama campaigned in poetry, then Sanders employs the prose of a Union Square pamphleteer telling anyone who’ll listen all the reasons why our country is going to pot.

And the college kids — they love it. At George Mason, they pump their fists and leap out of their seats and scream “I love you, Bernie!” They love him because he doesn’t sugarcoat it, doesn’t coddle them. As he rattles off the bad news, many students boo but others cheer; some cheer and boo. It’s almost as if they can’t help but applaud a candidate who has the nerve to give it to them straight.

Sanders greeting students after a town hall meeting at George Mason University. (Photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

No matter the setting or the audience, Sanders’ fundamental message is the same: The political system is broken, corrupt. Passing this or that new policy won’t fix it. In the mold of populists past, Sanders wants to tear it all down and rebuild it anew.

*****

When Sanders kicked off his presidential bid in May, his own allies were perplexed. He wouldn’t get within a mile of Hillary Clinton. Technically, he wasn’t even a member of the Democratic Party. (Sanders identifies as an Independent in the U.S. Senate.) But just as Donald Trump improbably stole the limelight among the Republican faithful after entering the race in June, for the Democrats the summer of 2015 was the Summer of Bernie. He drew huge crowds everywhere he went — 10,000 in Madison, 20,000 in Boston, 27,500 in Los Angeles. His advance team stopped booking reception halls and started booking sports arenas. The people loved it. The numbers proved it. Feel the Bern.

In a span of months, Sanders erased Clinton’s double-digit lead in polls conducted of Iowa and New Hampshire voters. He announced in October that his campaign had raised $26 million in the previous three months — just shy of Clinton, despite running a vastly leaner campaign and relying almost entirely on small-dollar donors. Several weeks later, Sanders told supporters that he’d received contributions from 750,000 individuals, a figure surpassing Barack Obama’s tally at the same point in his historic first presidential bid. And Sanders had gotten there more or less organically: For the first five months of his campaign, Sanders didn’t air a single TV ad. (Clinton’s campaign had aired more than 4,800 television ads through early October.)

Sanders greets supporters at a campaign rally outside the New Hampshire statehouse in November. (Photo: Brian Snyder/Reuters)

Sanders is now on the air in Iowa and New Hampshire, and while his polling numbers have started to level off, they climbed steadily from summer into fall.

There’s nothing new about insurgent candidacies emerging from what their supporters like to call “the Democratic wing of the Democratic party.” But in elections past — from George McGovern and Ted Kennedy to Bill Bradley and Howard Dean — they haven’t had much appeal beyond that well-educated, affluent demographic. What’s fueled Sanders’ rise and carried him past the point of vanity candidate is that he’s resonated with other voting blocs. White working-class voters like his vocal opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Retirees perk up when he defends Social Security and Medicare while denouncing pharmaceutical companies and the price of prescription drugs. Students take note of his call for affordable education. “Bernie is the first candidate to be brutally honest in acknowledging the fact that it is time for the government to stop making money off of student debt,” said Soophia Ansari, a student speaker at Sanders’ George Mason event.

Sanders may not walk into Philadelphia next July as the presumptive Democratic nominee, but he has attracted a broad enough base of support to make Clinton take him seriously. The Democratic debate in October was surely the first in recent memory to feature two candidates arguing over the definition of American capitalism. More important than Sanders’ chances of winning the nomination may be the underlying forces driving his unexpected rise. Who are the Berniacs and Sanderistas, as his fans are known, and what do they want? What’s so appealing to them about a grumpy, 74-year-old democratic socialist?

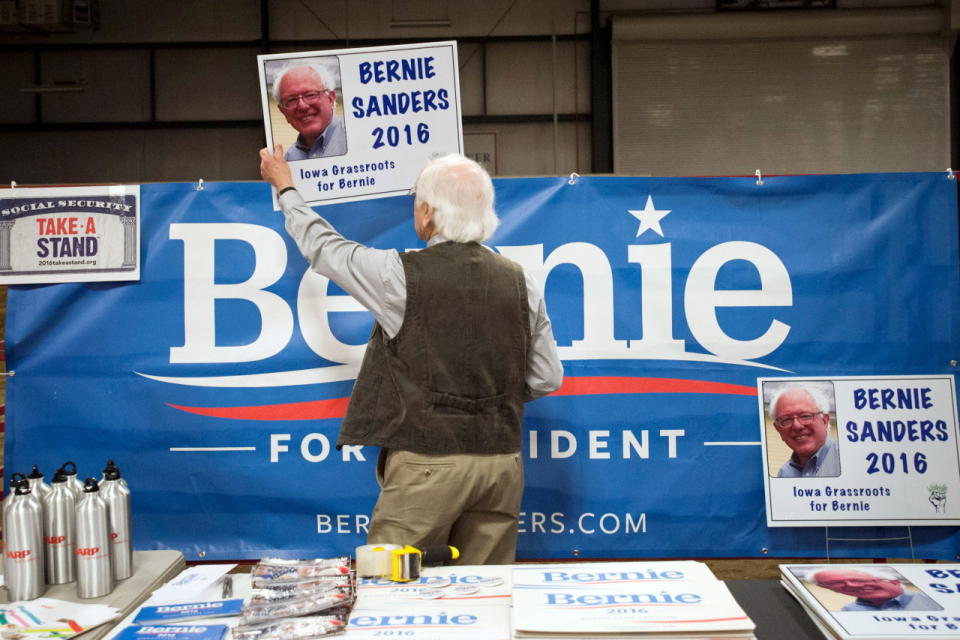

A Sanders supporter prepares a table at the Central Iowa Democrats Fall Barbecue in Ames, Iowa, last month. (Photo: Mark Kauzlarich/Reuters)

I spent several weeks following Sanders on the campaign trail and interviewing dozens of his supporters, Berniacs of all ages, races, ideologies and backgrounds. I met a man who had traveled from Finland to see Sanders in the flesh. I spoke to a family that had attended almost every single Sanders campaign event in the state of New Hampshire. I learned of a woman with terminal cancer who loved Sanders so much she’d decided to spend her final months volunteering for his campaign.

No two Berniacs are the same. Each discovered Sanders in his or her own way, and each has his or her own reasons for feeling the Bern. But what unites them is something larger, a deep rejection of a government that doesn’t tackle their everyday needs and problems. You hear a version of this on the Republican side, where Trump, for all his bullying and lies and vitriol, has tapped into a similar populist vein that cares more about offshoring American jobs, corporate mergers and too-big-to-fail banks than most of the rhetoric used by the current crop of presidential candidates. The Sanders-Trump crossover is real: Out on the trail, I lost track of how many times Berniacs brought up Trump as proof of something larger at play. One supporter I met in Nashua told me: “I’m kinda looking for Trump versus Sanders.”

*****

To live in New Hampshire is to be spoiled when it comes to presidential politics. The state’s first-in-the-nation primary status means the candidates spend inordinate amounts of time and campaign money there, and its residents can rattle off all the times they’ve seen “Hillary” or “Jeb” or “Kasich.” A friend of mine who lives in New Hampshire talks about “collecting” candidates like a kid collects baseball cards.

For decades, Sanders has been as the congressman — and later the senator — next door; before that, he was the widely known mayor of Vermont’s biggest city. There’s a familiarity to the way the people talk about him, a recognition that figures into Sanders’ strong polling numbers in the state. (RealClearPolitics’ polling average shows Sanders tied with Clinton, factoring in the margin of error.) People I spoke to expressed some surprise that Sanders had decided to run, but they soon recognized that the Bernie running for president was the same Bernie they’ve known all these years.

I caught up with Sanders during a two-day swing through New Hampshire at a senior center in Manchester. Standing in the corner of a wood-floored multi-purpose room opposite a Bingo board, kitchen and plaque listing the names of residents who’d rolled 300s in the Wii Bowling League, Sanders focused heavily on the nitty-gritty details of Social Security, chained consumer price index (CPI), protecting Medicare and the exorbitant cost of prescription drugs in the U.S. compared to Canada and Germany — issues all too relevant to most of the roughly three dozen audience members in the room. A burly man named Rick Maynard rose to his feet and thanked Sanders for the time he’d spent in New Hampshire, well before his presidential run, working with citizen activists and keeping people updated on the latest happenings on Capitol Hill.

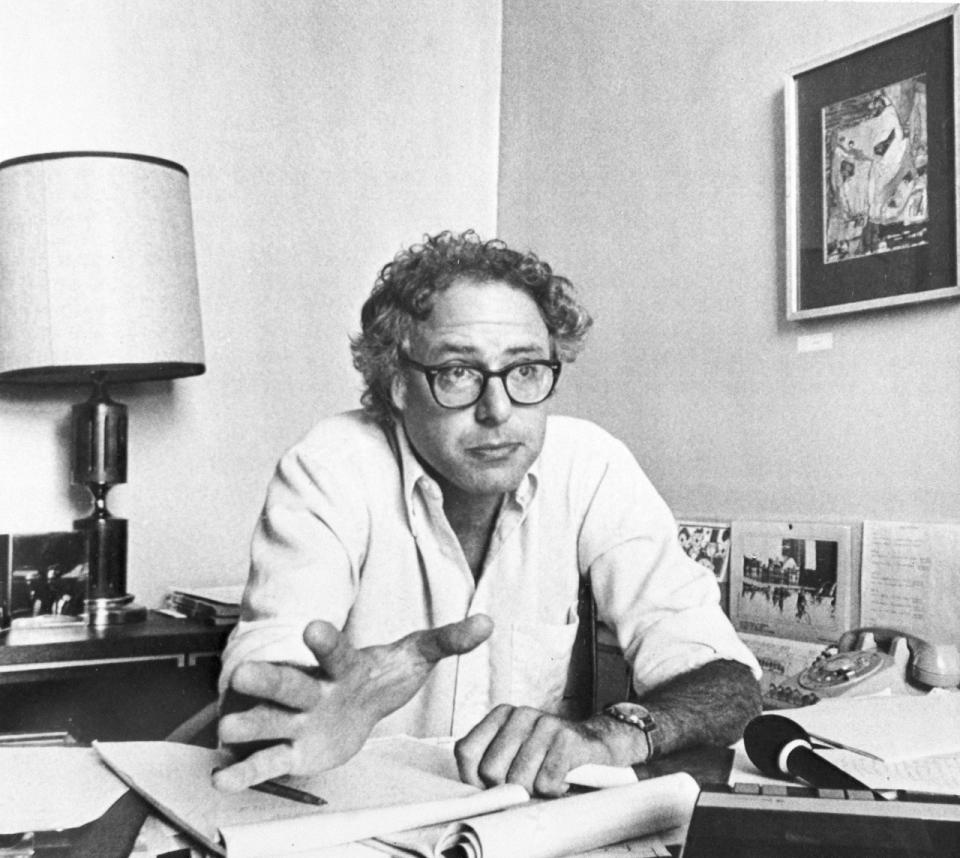

Bernie Sanders shortly after his surprise win as mayor of Burlington, Vt., in 1981. (Photo: Donna Light/AP)

I spoke with Maynard afterward. A 58-year-old unionist with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Maynard is a burly fellow, with chest hair peeking out of his T-shirt and “BERNIE” buttons pinned to his hat. He told me he was one of two people in the state who brief state legislators on trade issues. “Fair trade, not free trade,” he stressed. He praised Sanders’ consistency on the issue over the years, including his opposition to the TPP agreement. “He’s saying the same thing, possibly a little bit better because he’s got a bit more experience at it, but it’s the same,” Maynard said. “He doesn’t put the finger up and figure whichever way the polls are going.”

As for Clinton, Maynard referred me to a CNN story that found 45 different instances in which Clinton, as secretary of state, had praised the TPP. (As a candidate, Clinton came out against it.) “She flip-flopped. She kinda swayed in the wind,” Maynard said. “My concerns with Hillary are I don’t trust her, really.”

I heard that sentiment a lot about Clinton. Sanders, by contrast, is held up as a model of consistency and authenticity. He’s been giving the same wonky speeches for decades, and now it’s paying off by proving that he cares. In a world of hypocrisy, he is anything but a hypocrite. Long-time political columnist Walter Shapiro, who profiled Sanders 30 years ago when he was mayor of Burlington, puts it well, telling me: “Bernie Sanders was an angry man in 1985, and grumpy. He’s the same guy today.”

Hillary Clinton greeting Iowans at Iowa State University in November. (Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The other theme that comes up at Sanders events is an appreciation of his granular focus on the rising costs of getting by in America today. In the parking lot before a press conference at a local union hall, a third-generation union member named Zack Smith, 35, brings up — of all things — Sanders’ effort to reduce debit card transaction fees. “It’s the average person’s issues he brings up,” Smith said. He dismissed the notion that reforming debit card fees — an issue most visibly championed by then comedian (and future senator) Al Franken in his satirical 1999 campaign book Why Not Me? — wasn’t a winning issue with voters. “It is a big deal,” he insisted. “Four dollars and 52 cents is the average transaction for an ATM. That is absolutely ridiculous. People take out $20 a lot of the time, and 20 percent of that goes to an ATM fee?”

At the Manchester senior center, an older married couple, Michael and Doris Manning, talked with me about Sanders’ ideas on issues that intimately affect retirees and senior citizens. The Mannings are both 66; Doris has gray-blonde hair and wore Jack-o-Lantern earrings, and Michael wore a T-shirt that read “The Snoring He-Beast.”

“Since we’ve been retired now and on Social Security ourselves,” Doris said, “we know what he’s talking about.”

“It used to be a problem we were going to have to deal with someday,” Michael said. “Well, someday is now. And we find ourselves in exactly the types of situations he was describing.”

Doris said she was prescribed a medication that would cost her $265 a month. She couldn’t afford it on her and Michael’s income, so she opted not to take it.

“Same thing with my shingles shot,” Michael said. “For some reason it falls into the wrong category of drug. It’s a class B or whatever. Because it’s not covered, it’s 200-something dollars out of pocket. OK, I’m just gonna take my chances and hope I’m one of the two in three that don’t get it.” He continued, “You have those difficult choices to make. That’s why we tend to support people who tend to support us.”

What was their reaction to Sanders deciding to run for president? I asked.

Sanders supporters during a campaign rally at Cleveland State University in Ohio. (Photo: Aaron Josefczyk/Reuters)

“I was surprised,” Michael Manning said. “I thought that his views were too inconsistent with the prevailing sentiments in Congress and that he’d didn’t stand a chance.” He went on, “But this campaign year with Trump and all the other outsiders is going to prove me wrong across the board. I attribute that to a large extent because people are just disgusted with the prevailing views that are out there.”

“It’s nice to be wrong,” Doris chimed in.

“In this case,” Michael agreed, “it’s nice to be wrong.”

*****

At the other end of the age spectrum, Sanders’ fandom among young people has given rise to an unlikely nickname for the senator: the “Betty White of American politics.” Yet his campaign is anything but old-school. Numerous alums of Barack Obama’s digital media team work for Sanders, mimicking and improving on Obama’s use of technology and social media to reach and enlist young people who increasingly spend their days online.

Nearly every Bernie fan under the age of 40 that I met said they’d first learned about Sanders online, from his campaign website or Facebook page or live-trolling on Twitter during the second GOP debate, or they kept tabs on his campaign via social media. “On social media, on Facebook,” said Nardos Assefa, a University of Virginia student I met outside the George Mason rally, “you see little snippets of videos that are shared from Bernie’s speeches because he’s funny, he says things that are important to people.” The videos her friends are constantly flagging could be anything from Sanders’ denunciation of the school-to-prison pipeline to his delightfully awkward appearance on Ellen DeGeneres’ show.

“When I scroll through my news feed,” Assefa told me, “it’s, like, Bernie. I don’t see any others.”

What they’re seeing on Facebook and Twitter and in their inboxes stands in many ways as a rebuke of Obama. The Obama brand, if you will, was historic, aspirational, feel-good: “hope” and “change you can believe in.” Sanders is the anti-brand. He’s the “normcore” candidate. He’s not cool, he’s earnest. And that earnestness is in part what draws today’s generation of young voters — who were in middle school when Obama first ran for president — to the Sanders campaign. These are the late teens and 20-somethings who grew up on “Parks and Rec,” who watch Stephen Colbert. They’re not all about irony; for them, it’s OK to care.

And it’s OK to think bigger than you’ve been led to believe. After the town hall, I met a GMU sophomore named Faith Huddleston Anderson in a “Feel the Bern” T-shirt. In Sanders, Huddleston Anderson hears a politician stretching the limits of what she’d ever thought possible in the lives of people like herself. “Everything he said are things that I’ve thought in my head but never said out loud because it’s such an outrageous thought,” she said. “The idea of college being affordable is such a wild thought.”

She went on, “Us just having the idea in our head of free tuition feels a lot better to reach for than just reaching for, ‘Oh, we should get some reduced prices.’ I’ve always been told college shouldn’t be this expensive. But I’ve never heard anyone say it will not be.”

*****

The host said to look for the house with the solar panels on the roof, but it was dark when I arrived and I couldn’t see much of anything, except for the fleet of cars lining the cul-de-sac in a pleasant neighborhood a half-hour’s drive north of Washington. It was the night of the much-anticipated first Democratic presidential debate. The Sanders campaign’s handy interactive map showed an impressive 4,000 watch parties around the country. I’d chosen to watch the debate — and the debate-watchers — at the home of Hank Rappaport and Gina Angiola, both doctors and dyed-in-the-wool liberals. Books by Greg Palast, Naomi Klein and Noam Chomsky lined the shelves; I noticed a handwritten note listing the channel numbers for Current TV and Jon Stewart.

The CNN online feed on Hank’s laptop in the basement kept freezing (“Must be the DNC,” someone joked), so a bunch of us relocated to Hank and Gina’s living room, plopping down on couches and folding chairs and the floor to watch on the big TV. People cheered and hollered after each of Sanders’ turns to speak. They fell silent and sometimes jeered when Clinton talked. They were unsure how to react when Sanders delivered the line of the night, telling Clinton that the “American people are sick and tired of hearing about your damn emails!” And unlike the pundits who filled the TV screen once the debate ended, they believed that Sanders had won hands down, despite a strong showing by Clinton.

Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders speak during the Democratic presidential debate on Oct. 13 in Las Vegas. (Photo: John Locher/AP)

Afterward, we sit around talking about Sanders and what drew the people in the room to his campaign. The attendees skew middle-aged and older, and several have worked for progressive causes and candidates for years. Michael Rubinstein says he’s worked his whole life as a volunteer and as a paid staffer lobbying and grassroots organizing for social justice issues. After a career in medicine, Gina Angiola, one of our hosts, organized for Howard Dean in 2003, was a precinct coordinator for a liberal Maryland state senator and ran the Montgomery County office of Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.). Angiola describes herself and the other Bernie supporters like her as “the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party.”

These are, in other words, the people you’d expect to support Sanders. They remember the wilderness of the Clinton years. They believe it was the Democratic Party insiders — not the candidate’s own flaws — that took down Howard Dean in 2004. They supported a single payer health care system as part of Obamacare. They have mixed feelings about Obama’s presidency, and they wished Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., had run for president. They are the bloc of Democratic voters that can’t stomach the establishment, and so they seek out and rally behind more liberal alternatives, anyone from George McGovern in 1972 to Howard Dean in 2004 to Obama or even Dennis Kucinich in 2008. And now Bernie.

Rubinstein, the social justice activist, said he dismissed Sanders initially, but felt drawn to the senator after reading about the huge crowds turning out for him this summer and seeing 100,000 people tune in for a digital town hall he hosted in July. Sanders, Rubinstein said, reminds him of the Howard Beale character in the movie Network. “He’s the guy who’s telling you to put your head out the window and say ‘we’re mad as hell and not taking it anymore,’” he said. “He’s tapped into this kind of anger.”

I asked Gina Angiola, the host, how she got turned on to Bernie, and she nodded to her husband, Hank. Although Gina is the political junkie, in this case Hank found Bernie first, and suggested hosting one of the Sanders campaign’s telecasted town halls in July. Hank loves Sanders’ “fire and energy and anger,” and one line of Sanders’ sticks with him: “He said, ‘Obama’s great, but he did one major thing wrong: He built up a huge grassroots organization to get him elected, and on the day he took office he said, ‘Thank you all very much. I’ll take it from here.’”

Murmurs of agreement filled the living room. “That’s a fabulous line,” Gina said.

The thing is, it’s a line not wholly intended for the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party. The Michael Rubinsteins and Gina Angiolas of the world are already onboard with Sanders’ political revolution. It’s a line instead aimed at the masses of people out there — Democrats, independents, you name it — who feel the deep rejection of make-believe politics and dysfunctional government. People who feel the fear and anger that both Sanders and Trump are tapping into, who want an antipolitician, a candidate above it all.

Donald Trump addresses supporters during a campaign rally at the Greater Columbus Convention Center on Nov. 23 in Ohio. (Photo: Ty Wright/Getty Images)

“The Trump phenomenon and Bernie people are really sick of the political machinery in both parties,” Angiola told me when we spoke by phone a few days after the debate. “I think that the fact that Trump, Carson and Sanders are doing so well is a reflection of how disgusted people are with the political system. And they want people to talk straight. Stop mincing words.”

The clearest distillation of Sanders’ appeal came near the end of the first Democratic debate. “I believe that the power of corporate America, the power of Wall Street, the power of the drug companies, the power of the corporate media is so great,” he said, “that the only way we really transform America and do the things that the middle class and working class desperately need is through a political revolution, when millions of people begin to come together and stand up and say: Our government is going to work for all of us, not just a handful of billionaires.” In other words, Sanders wants power in order to challenge power, to stand up to JPMorgan and Comcast and GlaxoSmithKline. His pitch is that he needs working people, the Berniacs and Sanderistas, to have any hope of making that a reality.

Of course, it’s easy to dismiss such talk — “Bernie, I don’t think the revolution’s going to come,” quipped former senator and then Democratic candidate Jim Webb — but it’s impossible to argue that Sanders isn’t tapping into something larger. It’s a sentiment and an argument that may not decide who wins the Democratic nomination but could very well offer a glimpse at the future direction of the Democratic Party.

Andy Kroll is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist. He’s reported on politics and national affairs for National Journal, Mother Jones, and Men’s Journal, among others. He tweets at @AndyKroll and hails from the great state of Michigan.