John Lewis talks about his graphic novel — and his amazing life — to teenagers in jail

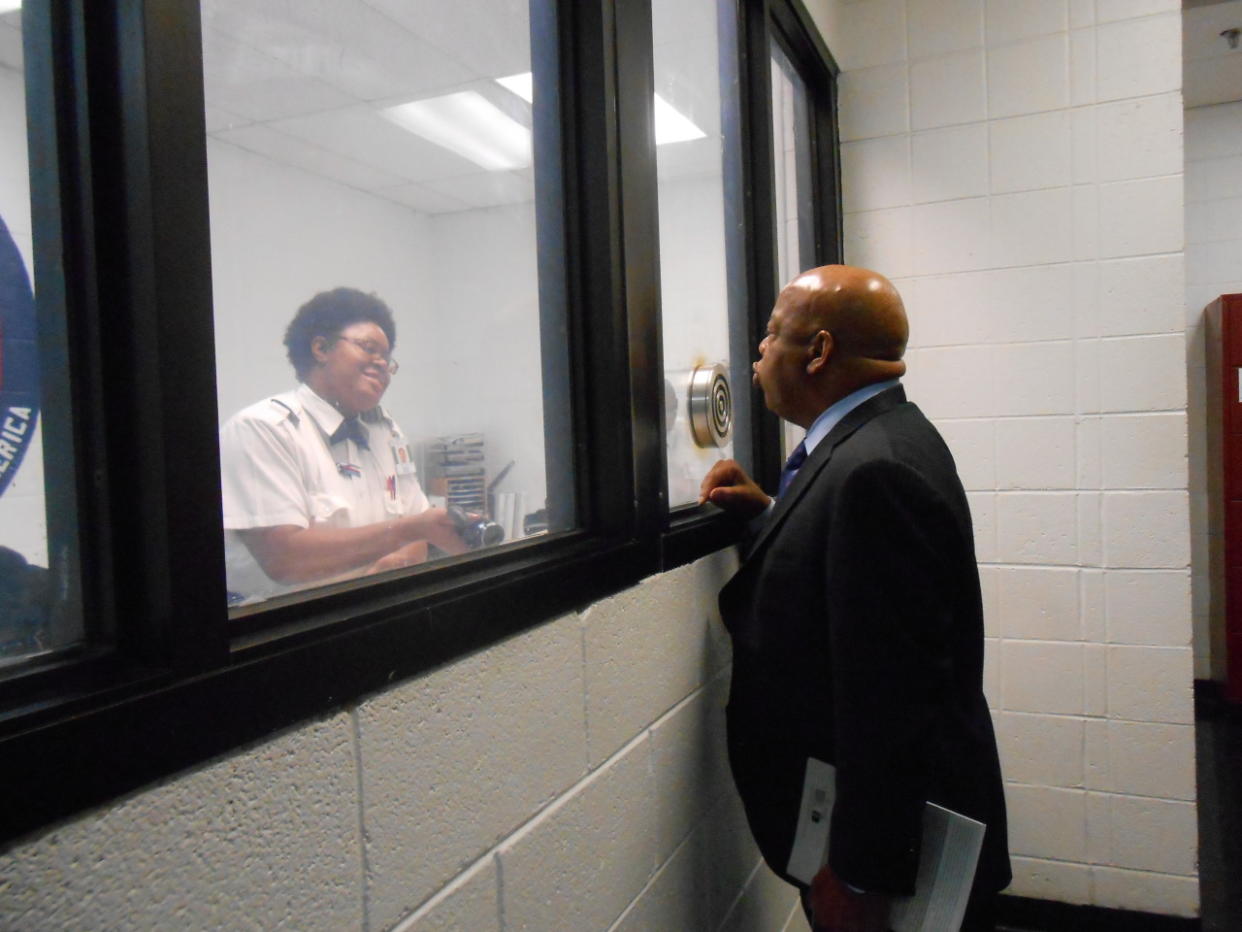

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., speaks to a D.C. corrections employee who recognized him from behind the glass of the jail’s entrance. (Photo: Meredith Shiner, Yahoo News)

Rep. John Lewis sits in a circle of chairs among 20 incarcerated teenagers in the makeshift chapel of a Washington, D.C., correctional facility less than 2 miles from the United States Capitol.

Unlike most of his colleagues in Congress, Lewis knows what it’s like to be in jail. In the 1960s, he was arrested 40 times as a result of his work as a nonviolent protester in the civil rights movement. A half century later, he sits in this jail on a hill, in a city where 535 members of Congress serve but few take the time to learn anything about the people who actually live here. These 16- and 17-year-olds live here. They’ve been charged as adults under the District of Columbia code, and as they sit attentively listening to Lewis, it’s hard not to think that under more normal circumstances they could just be school kids in a library instead of inmates. They are members of the Free Minds Book Club, a group that helps promote literacy and writing skills among incarcerated youth. Lewis is the co-author of a graphic novel, “March,” about his life and the history of the civil rights movement, and the group, having read it, has some questions for him.

“What made you go back to the bridge after you were beaten so badly?” a teen asks Lewis. (Because they are minors, they need parental consent to be identified in media accounts.)

With a preacher’s cadence, Lewis answers, “I go back to be renewed. I go back to be inspired.” His chair is positioned in front of where the pulpit stands at the focus of the room. Sayings, printed out on computer paper, hang on the wall behind him: “The church that God built.” “Lord speak to my heart.”

Though he does not say so explicitly, a major theme running through Lewis’ answers is that over the course of his 76 years, he has turned the most painful junctures of his life into symbols of optimism and hope. He tells the group that he has returned nearly every year to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. — including last year with President Obama and the first family to mark the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when he was beaten.

Another teen speaks up to ask Lewis whether there was ever a time when he thought he wouldn’t survive. He talks briefly about that day, but then cites a recent trip to Birmingham and the evolution of America he’s seen firsthand.

“I was arrested. I was jailed in Birmingham. When I go back there [today], they have a white police officer guarding me, and he tells me, ‘I’m a white Republican, but I would take a bullet for you. I would follow you. You changed America,’” Lewis says.

“You should always have hope,” he continues, before stopping to ask if the kids have heard the Pharrell Williams song “Happy” or seen the video of Lewis dancing to it on the Internet. “You should always be happy.”

Another teen asks if Lewis would be willing to dance for the group. He declines by noting he’d need music and doesn’t have any with him. But he adds: “If it hadn’t been for music, the civil rights movement would have been like a bird without wings.”

Lewis speaks to 20 incarcerated teens at a D.C. jail less than 2 miles from the U.S. Capitol. (Photo: Meredith Shiner, Yahoo News)

Deangelo Johnson, a 17-year-old member of the book club who has been in jail for 10 months, says he felt very inspired by the congressman’s visit.

When asked what he learned from the talk, Johnson says: “That any black man can be who we want to be and that we shouldn’t give up. … Maybe I can stand up and come back and talk to young juveniles.

“He was with Martin Luther King. He was Martin Luther King’s messenger,” Johnson continues. “I want to come back just like he did and say it’s not wrong to change.”

Lewis speaks to a new generation of youth now about civil rights, in person and through his graphic novels. He has written two of them with his staffer Andrew Aydin. Aydin, an Atlanta native who as a kid used comic books as a form of escapism, had the idea for the graphic-novel series when Lewis told him that King himself had edited a 10-cent comic about the civil rights movement.

No one thought more about this visit to the correctional facility than Aydin, a 32-year-old aide and lifelong constituent of Lewis, who worked with the D.C. Department of Corrections for months to arrange it. He tells the young adults there that he had been thinking about them and urges them to continue reading and writing. He also tells them to find mentors to help them along the way. Aydin’s father left him and his mother when he was 3 years old, he tells the kids, and he turns to the congressman as a father figure for guidance.

Before the talk, Aydin told Yahoo News: “If I had one more bad day, it would be entirely possible that I could have ended up in the same situation that a lot of these kids are in. And that means that I owe it to them to go back and hopefully tell them a little bit about myself and tell them about the people in my life who made a difference and made sure I didn’t end up there. These are just kids, and none of them have done anything bad enough to mean that their life should be over. There are few people who know more about going to jail than John Lewis and even fewer people about being on the right side of history. I hope that he can inspire them but also inspire all of us to do what is necessary to ensure that all of these kids get the opportunities they deserve to live a good and decent and fulfilling life.”

According to Free Minds Book Club staffers after the talk, that’s exactly what Lewis did. The kids are rarely as engaged or quiet or interested in other authors who come to visit. This particular talk, the first for the group from a member of Congress, was different.

Keela Hailes, the reentry facilitator for Free Minds and a self-described “Free Minds mom” (her son was a member of the club when he was 16 — he is 25 now and still incarcerated), was overwhelmed by Lewis’ appearance.

“It was beyond special. It gave me so much hope, I had to compose myself. For him to come here, knowing the situation of these young men, there are no words for the encouragement he provided,” Hailes says. “I cannot express how happy I am for these guys. … Their spirits can be so downtrodden, and looking how they are in his presence, it’s overwhelming and it’s awe-inspiring.”

At their last book club meeting before Lewis’ visit, about 10 Free Minds members collectively wrote a poem for the congressman. On Tuesday night, they read it for Lewis and present him with the first-ever framed version of a poem penned by Free Minds teenagers inspired by a work they read. The poem is titled “Free Minds March.”

Sacrificing myself and my family for rights and education

Fighting through these ropes of segregation

Killing them with kindness and no irritation

To make an impact on this great nation

We would take the word “nigger”

Instead of pulling a trigger

We were beaten and broken down to little pieces

To pave the way for our little nephews and nieces

We wanted nonviolence, but they gave us hatred

We gave it to the world, sat back and were patient

Rosa Parks wouldn’t give up her seat

Because she wasn’t going to let racism repeat

So we sat at lunch counters asking to be served

We got spit on and yelled at, but didn’t get disturbed

Congressman Lewis …

If you and Dr. Martin Luther King didn’t have a dream

We wouldn’t have equal rights in 2016!

Lewis hugs every young man who stood up to read the poem. He and Aydin sign their books, and then the congressman has to leave to return to the Capitol for late-evening votes.

On the short drive back to the Capitol, Lewis reflects on the experience.

“It was just very moving,” he says quietly from the passenger seat of the car, noting how impressed he was by the young men he met. “There was such a warm spirit there.

“I tell you, sometimes you have to think what happened,” he says, pausing for a long moment as he contemplates the past two hours and the lives of the 20 young men he just met. Rain pouring down, the car drives past the congressional cemetery and eventually turns onto East Capitol Street, with the under-construction dome of the Capitol in full view. “It’s a reflection on society.”

Lewis shook the hand of every teen who came to hear him speak Tuesday evening, as he and his staffer Aydin gave a book talk. (Photo: Meredith Shiner, Yahoo News)