Is Ben Carson an impostor?

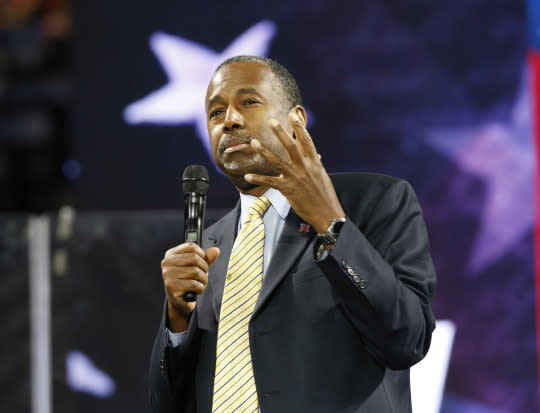

The issue surrounding Ben Carson, we’re told, is integrity — whether he made up stories to create a persona that isn’t real, and thus whether he can be trusted to lead. (Photo: Steve Helber/AP)

There are plenty of reasons to wonder if Ben Carson is qualified to be president. In Tuesday’s debate, while making an otherwise reasonable point about the mortgage interest deduction, Carson breezily asserted that all kinds of Americans had been buying houses before the income tax was enacted in 1913. (Yeah, not really.) He seemed completely confused talking about bank bailouts and how to prevent them. I’m pretty sure my own doctor knows more about governance.

But should we really question Carson’s integrity, given some of the doubts that now surround his personal story?

Here I have some qualms. Because the scrutiny of Carson’s personal story most closely mirrors what happened when a supremely qualified Democrat ran some 30 years ago — and it raises for me a lot of the same reservations about my own industry.

As you probably know, Carson has been pilloried over the past week for some of the more striking anecdotes in his autobiography, “Gifted Hands,” which also became a TV movie. It seems that maybe he did not actually try to stab a childhood friend or bludgeon his mother with a hammer, nor can it be verified that he was offered admission to West Point by Gen. William Westmoreland.

Let’s leave aside the fact that, in most pursuits in American life, not trying to kill one’s mother is considered a net plus. The issue here, we’re told, is integrity — whether Carson made up stories to create a persona that isn’t real, and thus, as the Fox Business moderator Neil Cavuto put it, whether he can be trusted to lead.

After Tuesday night’s debate, Carson tried again to put all this to rest, vowing not to answer any more carping questions about his past. “I’m going to choose not to talk about them,” he told my Yahoo colleague Hunter Walker, “because I would be talking about them from now until the election, and I’m not going to let people drive this.”

Now, if you ask me, there’s no small amount of hypocrisy here. As I’ve written before, Carson’s entire campaign — to an extent rarely seen in American politics — is a product of his personal narrative. Were it not for his story of rising from poverty and alienation to become the world-famous neurosurgeon who separated conjoined twins, no one would have thought for more than a nanosecond about Carson as a tenable candidate.

If you’re going to run on nothing but a story, then I guess we have a right to scrutinize that story more than we might, say, the zany tales of Jeb Bush’s Kennebunkport summers.

But that doesn’t mean we learn what we think we learn in the process.

Biography has always played some part in campaigns, of course. It’s just that, until pretty recently, no one exerted a lot of time and energy to fact-check every cherished anecdote. No one went traipsing through Kentucky in search of the spot where Abraham Lincoln supposedly split a forest’s worth of logs.

Like so much else in modern politics, that all started to change after Watergate, when issues of character and morality moved from the background of media coverage to center stage. After Richard Nixon’s implosion, political journalism became, as much as anything else, an exercise in psychoanalysis and lie detection. The less known you were, the greater the scrutiny.

The first real test of this biographical vetting role, perhaps, came in 1984, when a little-known senator named Gary Hart beat Walter Mondale, the former vice president, in New Hampshire’s Democratic primary. As I described in my book about Hart and political journalism, the new, post-Watergate generation of reporters immediately descended on Hart’s family and his boyhood home in Kansas, and what they found troubled them greatly.

It turned out that Hart’s name hadn’t always been Hart; the entire family had changed it from Hartpence. Mysteriously, Hart had also changed his signature at some point, so that letters he signed in the 1960s looked different from those in the 1980s. Hmm.

Also, Hart’s Senate biography said he had been born in 1937, but his birth certificate (yes, even then, people were always on about birth certificates) said 1936. Theories abounded.

The broader point in all these endless stories about Hart’s identity, which culminated in his political undoing three years later, was precisely the same one that journalists see now in Carson’s inconsistencies. The implication was that Hart was not who he said he was — that he was a kind of modern Jay Gatsby, a story fashioned from myth and ambition. And such a man could not be trusted.

In Carson’s case, as in Hart’s, there are a few problems with leaping to this conclusion. For one thing, it ignores an intrinsic American reality, which is that most of us, to one extent or another, reinvent ourselves as we go. That’s the nature of a land to which families fled from someplace else, or to which some were brought in chains, to adopt new names in unfamiliar places.

Like Don Draper running from a past no one really cares about anyway, Americans — and maybe successful Americans especially — are always experimenting with their stories and their identities. We are an ever-evolving people, and I’d bet few of us would want our own, self-narrated versions of our formative years — or our signatures — subjected to granular scrutiny.

Perhaps more to the point, though, such scrutiny fails to make a critical distinction when it comes to measuring integrity — namely, the distinction between the stories a politician might contrive to tell you, on one hand, and the stories he has always told himself on the other. As one of our most celebrated presidential historians, Robert Dallek, put it when we talked this week: “I don’t know that these guys consciously go out and create heroic myths about themselves. It’s part of their innate grandiosity.”

It seems very likely that, at least until this week, Carson had always believed he tried to kill his friend and that he spurned West Point to become a doctor. So what. That doesn’t make him an impostor. It makes him someone who found meaning in some pivotal moments of his boyhood, even if memory sharpened the edges a bit.

And these kinds of moments, real or embellished, have value when we assess our candidates, if we’re not looking at everything through some superficial, true-false lens. Carson’s book, which I devoured in a day, probably doesn’t tell us much about his trustworthiness now. But if you’re reading with any genuine curiosity, it can tell you an awful lot about the way he sees his own journey.

It explains the sense of destiny that propels a man who has never held elective office — and doesn’t know very much about government — to suddenly get up one day and seek the presidency.

This was the essential wisdom I took from my friend Richard Ben Cramer, who wrote the towering book What It Takes about the 1988 campaign, and I’m guessing he would have said the same thing about this Carson business, were he still with us today.

The things politicians believe about themselves are often a lot more illuminating than the truth.