How Trump’s ‘bullying’ would play against Clinton

Illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP

Hillary Clinton has always been at her strongest when she has seemed most vulnerable. From her soaring popularity during the impeachment hearings of her faithless husband to her brief electoral comeback in the New Hampshire presidential primary in 2008 after misting up in a diner, one of the most battle-scarred figures in American life has proven again and again that she has the capacity to rouse voters’ empathetic instincts.

Now, as Super Tuesday’s results bring us closer to a general election between Clinton and Trump, two brash New Yorkers who do not shy away from a fight, an unprecedented question looms. How does a man whose insults and old-school machismo only amp his popularity compete against a woman who has made an art form of turning the other cheek to such attacks?

In other words, how ugly will things get should Donald Trump run against Hillary Clinton? And how good — or bad — for each of them might that be?

“It will be a war,” says Rebecca Traister, who wrote a book, “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” about Clinton’s 2008 race, and has just published another, “All the Single Ladies,” about Clinton’s most important constituency this time around. “Trump is popular because he is channeling the anxiety of those who are losing power — white men — to those who are gaining it — women and minorities— and he is willing to say anything that expresses that hate.”

Certain conventions have been accepted about the political ground rules for running for office as a woman and for male candidates running against a woman, wisdom carefully accumulated over the decades by consultants working with focus groups.

Now, all of them are about to be upended.

Men are more analytical and women more emotional? Many voters see it the other way around this time. Men are traditionally seen as insiders while women are seen as outsiders? Those roles are flipped in the cases of Clinton and Trump. Women, arguably, are traditionally credited by voters with honesty and the ability to bring about change. Those are Clinton’s weakest areas, according to pollsters (though Trump doesn’t fare well on the honesty count, either).

And then there is a long list of things that men are supposed to avoid when running against a woman candidate: Never call her names, insult her looks, patronize her, act like a bully, encroach upon her physical space or appear physically threatening. (No, until this campaign, it wasn’t considered good strategy to do this to candidates of any gender, but there is an added menace perceived by voters when a man appears to demean or humiliate his female opponent.)

Trump, though, has done most of these things to many people who have gotten in his way thus far in the campaign, including more than a few women. Megyn Kelly, for instance, whom he called a “bimbo” and suggested she was hormonally unstable. Or Carly Fiorina, of whom he said, “Look at that face! Would anyone vote for that? She’s a woman, and I’m not supposed to say bad things, but really folks, come on! Are we serious?” He’s had choice words for Clinton already, too, calling the fact that she used the bathroom disgusting and turning a vulgar word for penis into a verb to describe her loss to Barack Obama.

Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders, left, and Martin O’Malley resume the debate at St. Anselm College in Manchester, N.H., in December after Hillary Clinton was late returning from a break. (Photo: Brian Snyder/Reuters)

When and if Trump becomes the Republican nominee, will he stop?

Not likely, says author Michael D’Antonio, who spent four years studying Trump for the book “Never Enough: Donald Trump and the Pursuit of Success,” which was published last fall.

“That’s who he is,” he says. “I don’t think he respects women, I think he’s made to feel vulnerable by them, and the way he expresses that comes out as hostility.” D’Antonio concedes that Trump insults and demeans both men and women, but he sees an added edge in his interactions with women. Based on conversations with Trump and comments the candidate has made in public over the years, D’Antonio says Trump divides women into “who’s a 10 and who’s not a 10, who he would like to have sex with and who he wouldn’t. The impulse is so strong in him to attack, and to do it in the lowest possible way will be irresistible to him.”

Adds Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy, a Clinton supporter: “He has a long history of offending women, and he’s not likely to change his stripes. Trump’s never met a group that he couldn’t offend.”

The Trump campaign could not be reached for comment for this article. But Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen has previously told Yahoo News, “This notion that Donald Trump hates women, that he’s a misogynist — that’s just plain wrong.” And Trump himself has repeatedly claimed to “cherish” women.

Less clear is the effect that any such attacks might have on 2016 voters. Subtle sexist attacks have arguably worked against Clinton in the past. These include the backlash against Clinton in her efforts to reform health care during her husband’s presidency and the allegation at that time that she was running a so-called co-presidency. This animosity also informed the existence of groups like Citizens United Not Timid, reportedly founded in 2007 by Roger Stone, now a Trump supporter, which raised money to combat Clinton during her first presidential campaign, using the first letters of each word as its logo.

First lady Hillary Rodham Clinton stands by her husband, President Bill Clinton, in the White House in 1998, after he denied engaging in improper behavior with intern Monica Lewinsky. (Photo: Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

But none of those were full-on attacks directly uttered by an opponent, for which, historically, male candidates have paid a price, at least temporarily. Presidential candidate Barack Obama was forced to explain himself after he said, “You can put lipstick on a pig, and it’s still a pig,” because Republicans believed he was insulting Sen. John McCain’s vice presidential running mate, Sarah Palin. GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney faced a backlash in 2012, after referring to the “binders full of women” he had called for in staffing his cabinet as governor of Massachusetts.

The galvanizing effects of misogynistic comments are so well recognized that Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri has admitted that her campaign actively helped Todd Akin win the Republican nomination in the 2012 Missouri Senate race, bargaining that he would say something that would offend women in the general election. (His chances were shot after he let loose a line about “legitimate rape.”)

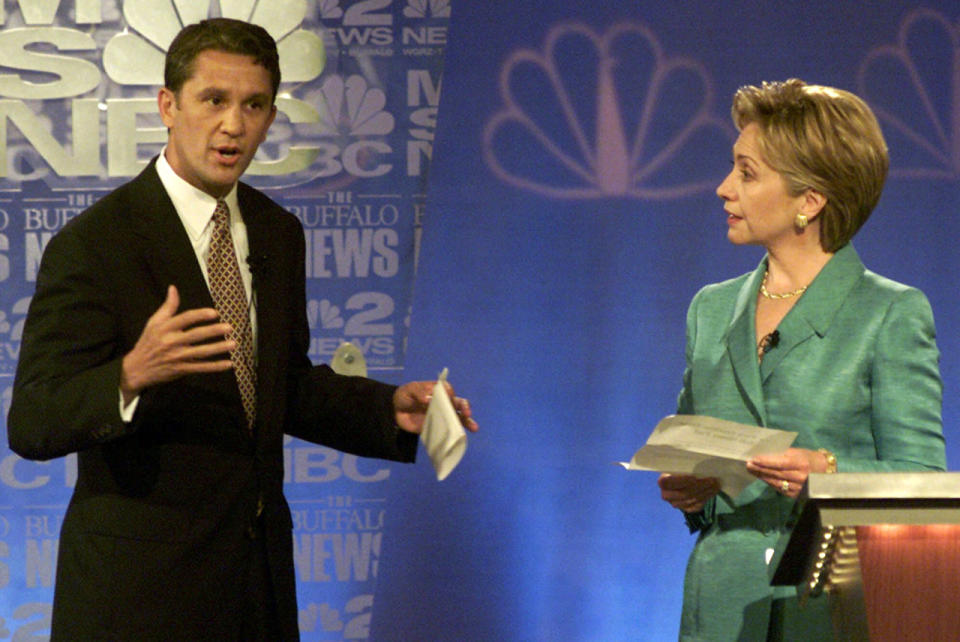

Add to that general guideline the more specific fact that Clinton has done particularly well when she is under attack. Think of such moments as the scandal over her husband’s infidelity, which resulted in Hillary Clinton’s highest approval rating in her two decades in public service. Or the first debate during her run for a New York Senate seat, when her opponent, Rick Lazio, marched across the stage, wagged his finger at her and waved some pages of a finance pledge in her face, demanding that she sign it. Post-debate polls (helped along by a lot of post-debate advertising by the Clinton camp) found that voters saw him as a sexist bully and that this incident marked a turning point toward her eventual victory. Another such moment came in the 2008 New Hampshire debate in which Obama told her, “You’re likable enough, Hillary.” The resulting outrage from women voters may have lost him the New Hampshire primary. Most recently, Clinton’s 11-hour marathon hearing before the Congressional Select Committee on Benghazi helped confirm the impression among many Democrats that she had proved her strength and stamina.

It would follow, then, that the coarser her opponents’ comments become, the better she will fare. But in a year where all bets are off, will this conventional wisdom work?

Former Rep. Rick Lazio, R-N.Y., left, approaches Hillary Rodham Clinton in the first debate in their race for the U.S. Senate in 2000. (Photo: Richard Drew/AP)

Already, Trump has turned the gender tables on Clinton, proving himself a skilled fighter on terrain that might have undone her other opponents. After Trump asserted that Clinton had been “schlonged” by Obama in the 2008 election, she responded that Trump had shown a “penchant for sexism.” He, in turn, accused her of playing the “woman card” and tweeted: “Hillary Clinton has announced that she is letting her husband out to campaign but HE’S DEMONSTRATED A PENCHANT FOR SEXISM, so inappropriate!”

A day or two of news stories and editorial columns followed, in which the focus shifted from Hillary the wronged wife to the Hillary who was willing to stand by her predatory husband.

Which leaves veterans and prognosticators in new territory. “It’s hard to judge Donald Trump on those kinds of things, because he says such strange, somewhat irresponsible things, and it hasn’t seemed to harm him in the primaries thus far,” says Dick Riley, who was Bill Clinton’s secretary of education and who has endorsed his wife. “People seem to respond differently to him than they have to other people.“

D’Antonio echoes this thought, saying: “You can’t predict anything about his effect on people.” He recalls a Trump rally where the candidate called out a male protester for being fat “and people in the room didn’t recoil, they cheered. Even though a lot of the people cheering were also fat. In order not to be the target, you join the bully.”

Liz Goodwin contributed reporting to this story.