Hijacked by their dream of a Cuban ‘paradise’

Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: background and posters via Getty Images, plane photo by Spashett via airliners.net

Anthony Bryant was once so enamored with Fidel Castro’s revolution that he felt compelled to hijack his way to Cuba.

In the wee hours of March 5, 1969, the 30-year-old Bryant, a Black Panther with a history of heroin-related arrests, used a revolver to commandeer National Airlines Flight 97 as it neared Miami. He ordered the pilots to head straight for Havana, the destination of choice for scores of American hijackers throughout the ’60s. Upon touching down at José Martí International Airport shortly before dawn, Bryant was certain that he was about to enter what he had dubbed “paradise.”

“Cuba was creating a true democracy — a place where everyone was equal, where violence against blacks, injustice, and racism were things of the past,” Bryant would later recall thinking as he was whisked away by soldiers, whom he expected to escort him to a comfortable hotel. “I had come to Cuba to feel freedom at least once.”

Given all we now know about the ravages of Castro’s autocratic rule, Bryant’s optimism seems baffling. But for more than a decade after Castro and his guerrilla comrades swept to power, a sizable number of Americans earnestly believed that Cuba had become a more equitable and more joyous place than the United States. Some of these devotees were so eager to experience Cuba’s utopian society firsthand, in fact, that they committed spectacular crimes to reach Havana. All but a handful of these adventurers would come to rue their naiveté.

Cuban Premier Fidel Castro waves to crowd who greeted him upon his arrival at New York City’s Penn Station on April 21, 1959. (Photo: Bob Schutz/AP Photo)

Many Americans romanticized revolutionary Cuba because they were smitten with Castro, a photogenic young lawyer who was adept at exploiting mass media. Just days after he overthrew the thuggish Fulgencio Batista in January 1959, Castro appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” to promise American viewers that he was going “to improve” his country’s “democratic institutions” so that Cuba would never again fall prey to a dictator; the starstruck Sullivan responded by favorably comparing his guest to George Washington. Three months later, during a whirlwind visit to the U.S., Castro hired a public relations firm to coach him on how best to win American hearts. In addition to participating in photo-ops with cute kids, captive elephants and Abraham Lincoln, Castro delivered a speech at Princeton University about his sincere desire to hold elections and improve the lives of ordinary Cubans. Americans who were charmed by Castro’s genial veneer and uplifting message often had trouble shedding their faith in his innate goodness, even as hints of his authoritarian streak began to emerge.

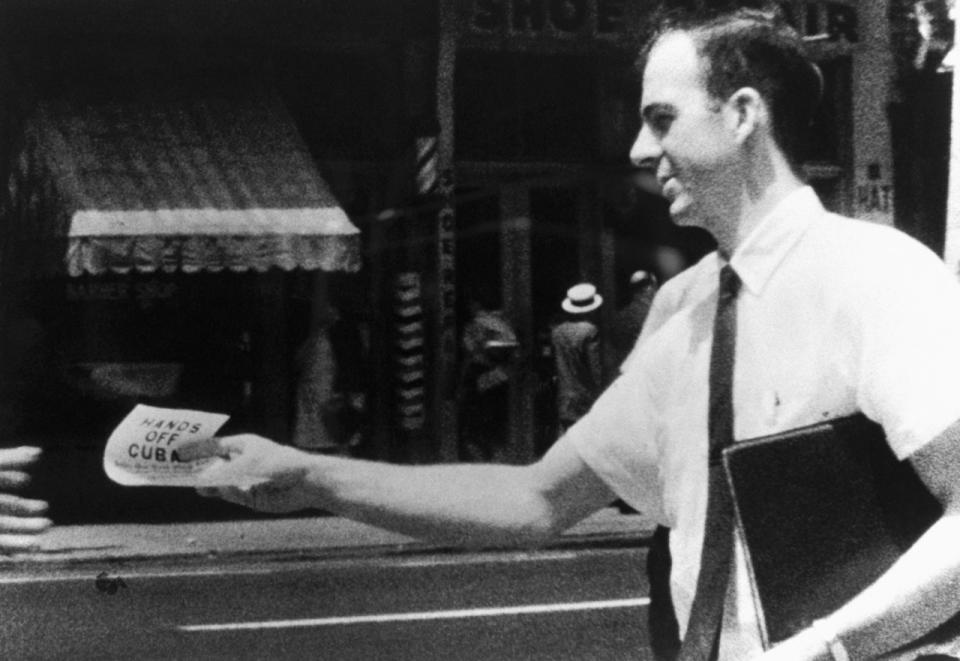

After the Kennedy administration decided to isolate Cuba by enacting a travel ban and a total economic embargo in February 1963, reliable information about events on the island became scarce. Americans were thus free to create their own elaborate fantasies about how Castro’s revolutionary experiment was unfolding. For people who were disillusioned by the escalating conflict in Vietnam, the backlash against the civil rights movement, or just their gloomy career or romantic prospects, it was tantalizing to imagine that an egalitarian promised land existed just 90 miles south of Key West. Among the bewitched was Lee Harvey Oswald, who was filmed handing out pro-Castro literature in New Orleans three months before he assassinated Kennedy. (The founders of the organization that produced Oswald’s leaflets included such luminaries as Truman Capote, James Baldwin and Norman Mailer.)

Lee Harvey Oswald distributes “Hands Off Cuba” fliers on a New Orleans street in August 1963. (Photo: Corbis)

Rather than settle for merely idealizing Cuba from afar, some desperate or deluded souls opted to defect to the country aboard hijacked planes. Diverting a commercial jet to Havana was a simple affair in the ’60s: Only a small fraction of passengers ever had their bags or bodies inspected prior to takeoff, and flight crews were under strict orders to comply with a hijacker’s every demand. Instead of shelling out tens of millions of dollars to improve security on the ground, the airlines focused on streamlining the process of getting their hijacked planes to and from Cuba: They stocked each cockpit with maps of the Caribbean, for example, as well as phrase cards designed to help pilots communicate with Spanish-speaking hijackers. By the end of the decade, hijackings to Havana were so routine that Time published a how-to guide for airborne hostages. (Sample advice: “Don’t push the call button. The sudden ping in the cockpit might startle the felon and provoke him to fire his pistol.”)

Most of the hijackers assumed that great bliss awaited them in Cuba. Radicals such as Anthony Bryant thought the Cubans would hail them as comrades and train them to spread the revolution to every corner of the globe. Less politically inclined hijackers, meanwhile, looked forward to reinventing themselves as cheerful members of the proletariat: One 18-year-old girl from Poughkeepsie, N.Y., explained that she’d been captivated by the idea of escaping a decadent society obsessed with “cigarettes, Pepsi-Cola and pizza” in order to toil in an idyllic Cuban sugarcane field with her boyfriend.

But the hijackers quickly discovered that they were unwelcome guests. Castro was deeply suspicious of the Americans who showed up in Havana unannounced, and not without reason — the U.S. government was, after all, quite eager to kill him. He feared that some of the hijackers were CIA plants, while the rest were either hardened criminals or mentally ill malcontents who might destabilize Cuban society. So rather than celebrate the American fugitives, he treated them as security risks: After being strip-searched and interrogated by the secret police, the bulk of American hijackers were sent to live in a squalid dormitory in south Havana. Known to Cubans as Casa de Transitos and to the Americans as “Hijackers House,” the building was only marginally better than a prison: The residents were bullied by armed guards and forced to subsist on maggot-infested bread. When they were permitted to roam the streets of Havana, the dozens of hijackers were frequently abused by the locals — especially the African-American hijackers, who came to realize that Marxism had not eliminated racial prejudice.

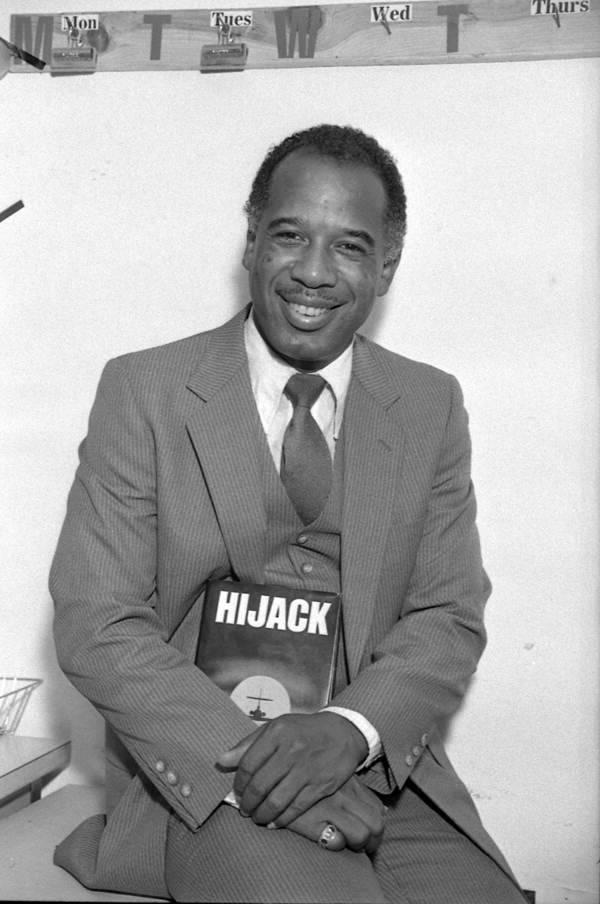

Writer Anthony Bryant holds his book “Hijack” in 1985. (State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory)

“They call us monkeys because we have Afros,” a hijacker named Richard Witt complained to a Penthouse reporter in 1973. “[The police] told me either cut the Afro or go to jail.” Like many of his roommates at the Hijackers House, Witt eventually turned so sour on Cuba that he elected to return to the U.S. voluntarily, even though doing so meant he had to face federal air-piracy charges.

The Cubans singled out a few hijackers for exceptionally brutal treatment, none more so than the unfortunate Anthony Bryant. Because he made the mistake of robbing his hostages of $1,700 while en route to Havana, Bryant was sentenced to spend 12 years in a tropical gulag. During his nightmarish incarceration, he was repeatedly tortured with bayonets and forced to witness the executions of political dissidents. By the time he returned to the U.S. in 1980, his politics had shifted far to the right. “Communism is humanity’s vomit!” he exclaimed during his first bond hearing in Miami. “Wipe it out!” Bryant was eventually sentenced to probation and became a conservative talk-show host; he was also once arrested for allegedly plotting a paramilitary assault on Cuba. He died of cancer in 1999.

Bryant’s political transformation during the ’70s mirrored that of the nation at large, of course: On the eve of the Reagan era, with the Cold War set to intensify anew, anyone who still idealized Cuba seemed like a relic from a bygone age. Castro’s revolutionary shtick had grown shopworn as his regime had atrophied and become ever more dependent on Soviet largesse. As a result, the Havana-bound hijackings had slowed to a bare trickle, especially right after the introduction of universal passenger screening in 1973. America’s daydreamers and disenfranchised had by no means vanished, but they’d wisely decided to look elsewhere for their earthly paradise.

Brendan I. Koerner is a contributing editor at Wired and the author, most recently, of “The Skies Belong to Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking” (Crown, 2013), from which reporting for this story was taken.