For Jeb Bush, humiliation made survival possible

Donald Trump was such an unmitigated joke to Jeb Bush that when Sean Hannity mentioned the businessman and reality TV celebrity in a mid-June interview on the day Trump announced his candidacy, Bush just laughed.

“Donald Trump took you up in a speech today about Common Core and immigration. I want to ask you—,” Hannity, a Fox News personality, said before he was cut off by Bush’s chuckling.

Voters watching Bush and Hannity inside the Derry Opera House, in southern New Hampshire, also burst out laughing.

“I’m sorry,” Bush said, earnestly, becoming serious again. “I shouldn’t have done that.”

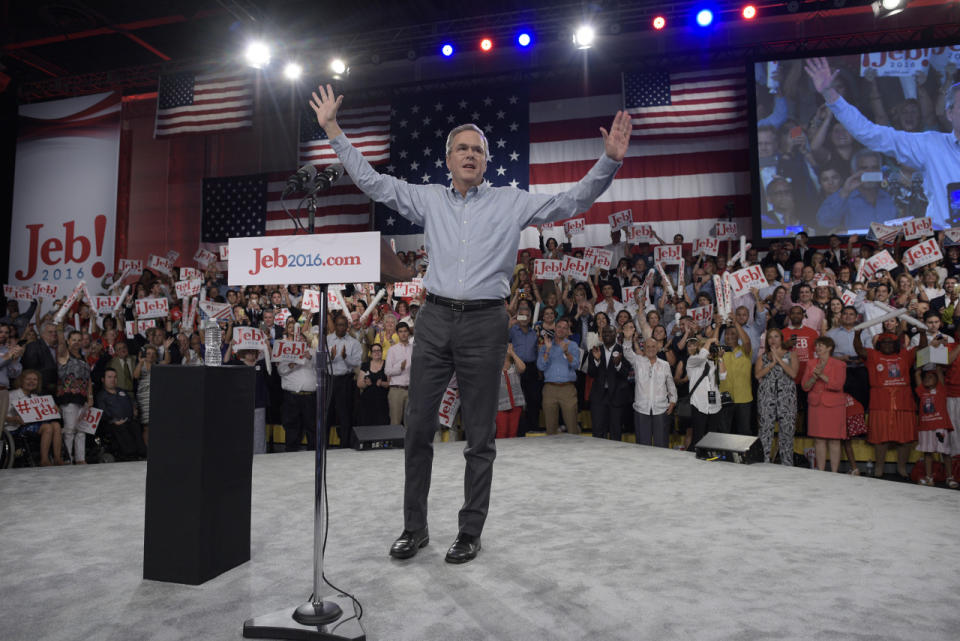

But it was the day after Bush’s official campaign kickoff, and the former Florida governor was riding high. He could afford to be gracious. Bush had a $100 million war chest between his campaign and the super-PAC supporting him. And his announcement in Miami the day before had been a joyful, multicultural affair.

Salsa music warmed up the diverse and raucous crowd of 3,000 people inside the Theodore R. Gibson Health Center gymnasium on the campus of Miami Dade College’s Kendall campus. Bush even spoke in Spanish for a few moments during his speech.

“Júntense a nuestra causa de oportunidad para todos, a la causa de todos que aman la libertad y a la causa noble de los Estados Unidos de América,” Bush said effortlessly. Translation: “Join our cause of opportunity for all, the cause of all who love freedom and the noble cause of the United States.”

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush announces his 2016 run for the White House at Miami Dade College in Kendall, Fla. (Photo: Charles Ommanney/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

His speech was just OK, but that didn’t seem to matter at the moment. Besides, Bush was ready to be president. “I know we can fix this because I’ve done it,” he said. He walked outside and signed autographs while standing at the window of a food truck.

For six months, life as a presidential candidate was pretty good for Bush.

“There are bumps in the road,” he told me in mid-July when I interviewed him at a tech company in San Francisco’s hip South of Market neighborhood. But they were just bumps. He had hit his highest number yet in the national polling three days earlier, rising to 17.8 percent of the Republican primary electorate.

Bush toured the sleek tech startup headquarters, joking with the young founders as he went. It was all a set piece to contrast with Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton, who was talking about regulating tech startups like Uber. Already, Bush was looking past his Republican competitors to the general election.

*****

Bush had no idea what he was getting into when he started running for president. Looking back at his campaign’s early days, it is striking how radically his fortunes have changed and how he has evolved in response. He has grown in many ways, but still remains a deeply flawed candidate who is eyed warily by many in the GOP who doubt his ability to beat Trump or Clinton.

Yet thanks to Marco Rubio’s huge debate stumble this past Saturday night, which allowed Bush to finish just barely ahead of the younger man in the New Hampshire primary, Bush’s candidacy is “not dead,” as he himself put it Tuesday night. It’s not clear that Bush is Lazarus, as some are saying, but those who support his candidacy say that the New Hampshire result is the first sign that he is on the way back.

But a key part of that resurrection, they say, is that Bush had to be humiliated in order to overcome the most fundamental obstacle in the way of his candidacy: his last name. Bush said in his announcement speech that no one “deserves the job by right of résumé, party, seniority, family or family narrative.” That was easy to say then when he was the presumptive favorite.

Now he’s been forced to demonstrate he really believes it, after soldiering on despite being dismissed for months.

Bush and Rubio at St. Anselm College in Manchester, N.H. Rubio’s stumble in last Saturday’s debate helped give new life to Bush’s campaign. (Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

“Everybody running for president is gonna get knocked down eventually. The test of whether or not you can get up was passed today in New Hampshire,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., who is supporting Bush. “Now we’re up on our feet, and we’re gonna run in South Carolina.”

Bush, his friends and supporters say, is a better candidate now because he has been pushed to the brink of elimination. Many Republicans remain deeply skeptical. But, nonetheless, it has been a long road to learn the lessons his camp says he’s learned.

He began as a candidate who delighted in poking his finger in the eye of the anti-immigration wing of the Republican Party. He denounced it as hurtful both to his party and to the country. Bush was intent on making the case that the U.S. needs higher levels of legal immigration. And most of all, Bush swore he would run a “joyful” campaign and would not give in to the politics of resentment or outrage.

“You don’t have to be angry,” he said on his first trip to New Hampshire in March, speaking inside the home of former state GOP Chairman Fergus Cullen, which was packed to the gills with voters and press.

“I’m not going to fake anger,” Bush said a few days later in Atlanta, “to placate people’s angst.”

Even physically, Bush was a different creature in those early days. On Dec. 1, 2014 — two weeks before he announced in a Facebook post that he was beginning to “explore” a bid — Bush traveled to Washington, D.C., for an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s D.C. bureau chief, Jerry Seib, at a CEO Council summit.

Bush sat opposite Seib onstage, legs crossed, leaning back in his chair and resting his arms on the sides. These were the days before he went on a Paleo diet that cut dairy and grain products out. His cheeks were fuller. When Seib asked him questions, Bush spoke in calm, measured tones, deliberately, but with complete relaxation and confidence.

Bush said he was thinking seriously about running for president, but had one major question. “Can I do it in a way that lifts people’s spirits and not get sucked into the vortex?” he said. Politics was “a nasty business,” he said, and he did not want to lower himself to insulting other candidates or to changing his positions in a way that violated his authentic beliefs.

He laid out what he thought any Republican candidate would have to do to become president: Inspire the nation and bring Republicans and Democrats together to tackle a handful of core challenges facing the nation — become energy independent, modernize regulation, simplify the tax code, reform the immigration system, and conduct a “radical transformation” of the education system.

SLIDESHOW – Jeb Bush through the years >>>

“We’re moping around like we’re France,” Bush said. “We’re not seizing the moment. We’re not aspiring to be young and dynamic again. And if we fixed a few really big substantive things — don’t get me wrong, these are not little things — we could be American again.”

It was Bush’s own way of saying he wanted to make America great again.

But rather than tapping into the aspiration that Trump’s simple slogan did, Bush’s candidacy quickly became defined by his two biggest challenges. He was the son of one president and the brother of another. And he was seen as soft on immigration and on the Common Core national education standards, issues that were anathema to the GOP’s right wing but also to many other voters who weren’t traditional Republicans.

Bush didn’t have a clear strategy on how to deal with his last name. And he was intent on charging through a wall on the issues.

He argued that increased levels of immigration were required to jump-start the economy and prepare the country for the retirement of the baby-boomer generation. And he said that the Republican Party had to “win votes” with a “hopeful, optimistic message.”

“Hope and a positive agenda wins out over an angry reaction every day of the week,” Bush said in late January 2015, standing on a massive stage inside San Francisco’s Moscone Center, in his first major speech as a candidate, to the National Automobile Dealers Association. He was legally “exploring” a run so that he could raise unlimited sums from donors that were funneled into Right to Rise, the super-PAC managed by longtime political adviser Mike Murphy.

As ran through his bullet points on the immigration issue, Bush countered critics of his support for a path to legal status by pointing out that there was “no way” the millions of undocumented immigrants were going to be deported.

“No one is suggesting an organized effort to do that,” he said.

That would change once Trump entered the race and capitalized on the resentment of large swaths of Americans who blamed the loss of many industry and blue-collar jobs on immigration.

*****

For a time, it seemed as if Bush might be able to fill the inspirational role he had described, carrying a happy warrior message and embracing confrontation and challenge, unlike the GOP’s 2012 nominee, Mitt Romney.

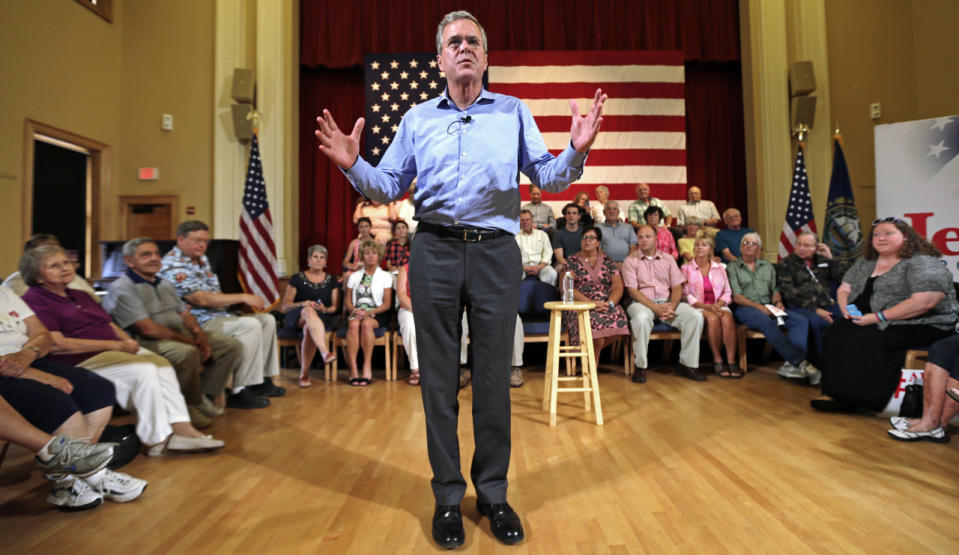

Early in the campaign, Bush at a town hall in Gorham, N.H., July 23, 2015. (Photo: Charles Krupa/AP)

When Bush hit the campaign trail with his trip to New Hampshire in late March, he impressed the reporters who followed him around with his accessibility, his knowledge and his confidence. Unlike Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who was the champion of the grassroots at the time, Bush was not afraid of reporters and ran toward them and their questions.

“I’m running a campaign that I hope will show the authenticity of why I’m running, and I’m running a campaign that gets me vulnerable,” Bush told me in San Francisco. “I’m outside my comfort zone. I do press gaggles.”

He also engaged robustly with voters. At Fergus Cullen’s house in Dover, Bush stood in a living room cleared of furniture and took questions from Cullen’s guests for an hour. Then he walked out into the driveway to answer questions from the press, trailing reporters who clambered over the two feet of snow still on the ground from the record snows of that winter. He wore no coat in the frigid temperatures, and his breath was visible in the harsh light of the TV cameras as he answered questions.

The anger of the electorate was becoming more evident to Bush, and he addressed it. The American people were frustrated, he said, because nothing got done in Washington. The way to lower the temperature, he argued, was to “forge consensus to solve these problems so people aren’t as angry.”

By April, Walker had faded. It was often pointed out that Bush’s supposed strategy to keep other rivals out of the race with a shock-and-awe fundraising effort — most obviously Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida — had failed to do so. But Bush was still the frontrunner.

But as the spring wore on, there were troubling signs of his flaws as a candidate.

In May, Bush fumbled a question about whether he would have invaded Iraq in 2003, knowing that there were no weapons of mass destruction there. Bush, incredibly, had not thought through if and how he would critique the definitive issue of his brother’s presidency. At first, he said he would have done the same, then said he’d not heard the entire question and said he didn’t know what he would have done, and then finally, after four days, he said he would not have ordered an invasion.

Bush was plagued by a series of verbal stumbles over the late spring and into the summer. Some were more careless than others. By and large, his comments were innocuous in their proper context, but easily misconstrued by political opponents who fed them to the press and generated headlines. In late July, Bush was yelled at by an older woman in Gorham, N.H., for saying he wanted to “phase out” Medicare. In early August, he made a remark about funding for women’s health that reinforced a growing image of him as a bumbling candidate who — when he responded with irritation to questions about each comment — was having anything but a “joyful” time of it.

Over the spring and summer, the relaxed, confident Bush began to disappear and was eventually replaced by a thin, almost gaunt man who increasingly spoke with a furrowed brow, straining with his voice and his body language to get across to voters that he understood their anger. His inability to break through produced obvious frustration, illustrated by a strident nodding of his head as he talked, like a woodpecker hitting metal.

The Jeb Bush that emerged from the pressure cooker of the presidential campaign was sped-up, hurried, desperate to change the laws of gravity that were dragging him down, no matter what he did.

He was perplexed. This was not how he had expected things to go. He had expected a vortex, but instead was marginalized by a clown show.

“The environment was never going to be welcoming to somebody who’s last name was Bush,” said one Republican operative who had worked in a high-level position in the George W. Bush White House and who gave informal advice to Jeb Bush’s campaign. “There was probably room to do better, but there was no room for error, and he made a lot of errors.”

On July 20, only a week after Bush had risen to nearly 18 percent in the national polls, Donald Trump passed him and led with 16.8 percent to Bush’s 14.8 percent. Bush would never be the frontrunner again.

*****

By the time the first debate rolled around, on Aug. 6 in Cleveland, Trump had shot up to 24 percent and Bush had fallen to 12 percent. Some of Bush’s backers were actually hoping their man would get bloodied onstage, to force him to elevate his game.

“I almost feel he needs to get punched in the face and then he’ll strap it on and get to work here,” said one person who talked to Bush semi-frequently. “If Trump and Jeb get into it and people say, ‘Jeb got his doors blown off,’ it may fire him up and get his juices going.”

That showdown never happened. Bush was offered the chance to take a swing at Trump when Fox News’ Megyn Kelly asked him if he’d called Trump an “a**hole.” Bush denied it, said quickly that Trump’s “language is divisive,” and quickly moved on to talking about his record in Florida.

“He is a true gentleman. He really is,” Trump said condescendingly of Bush and brushed aside Bush’s mild critique of his language. “When you have people that are cutting Christians’ heads off … we don’t have time for tone. We have to go out and get the job done,” Trump said.

Bush addressed supporters in Sioux City, Iowa, before the Feb. 1 caucuses, where he got just 2.8 percent of the vote. (Photo: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Bush was well on his way in Cleveland to becoming an afterthought. He looked like a deer in headlights, unable to condense his thoughts into coherent, bite-size nuggets. The former governor was realizing that modern politics had changed quite a bit in the eight years since he left elected office in Florida. The last time he had run for any office, in 2002, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter did not even exist. Not to mention that the national spotlight in a presidential primary was far hotter than anything he’d experienced as governor, even of a big state.

Trump, on the other hand, represented everything about the modern media environment that — for better or worse, and mostly worse — works in mass communications: bombast, arrogance, an appetite for provocation and outrage, and even an ability to brazenly lie, as he did most recently when he said he had never called Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., a loser.

August, for Bush, was the month from hell. He decided to take Trump on directly, calling attention to his past support for single-payer health care, partial-birth abortion, and massive tax hikes. It made no impact. But when Trump labeled Bush “low-energy,” it had a devastating effect. Late in the month, Bush traveled to the Mexican border and hit a new low, referring to Asian “anchor babies.” It was another careless comment by him, one that made him look craven and desperate and turned into a multiday cable TV news story.

And then, at an early September event in New Hampshire, a factory worker who had worked an early morning shift at a manufacturing plant nodded off behind Bush as he spoke, reinforcing the low-energy meme.

The Bush campaign was losing its mind over the way the press was covering the campaign. “I don’t think it’s unfair for the media to step back from the way they covered this race and actually look at these candidates, look at what they’ve done and stop the sensationalism,” Bush campaign manager Danny Diaz said this past weekend, summing up months of frustration.

“We’re not running in the school uniform election,” Diaz said. “We’re running as a country that’s at war, with an economy that’s not growing, and we have serious issues that need to be addressed. Having some track record of having done this should matter.”

The fall continued Bush’s slide into becoming a punch line. At the second debate, at the Reagan Library in mid-September, he started in on Trump with a potent attack: a true story of the time Trump tried to donate money in the pursuit of legalizing gambling in Florida and Bush had rejected him. But even when he had a slam dunk, Bush couldn’t score. Trump denied the story, and Bush let him off the hook.

SLIDESHOW – New Hampshire results are in >>>

Bush tried to interrupt Trump, who mocked him as if he were swatting away a fly. “OK, more energy tonight. I like that,” Trump joked. The audience laughed — at Trump’s joke and at Bush’s ineptitude.

At the third debate, in Boulder, Colo., Bush tried to go after Rubio for missing votes in the Senate but was smacked down by the younger man. Bush had played a role in helping Rubio rise up through the ranks in Florida and was now being pushed aside by his former mentee.

By the time the GOP candidates debated for the fourth time, in December, the press was well past focusing its attention on Bush. The showdown of the night was between Rubio and Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, over immigration.

*****

After the New Year, Bush remained largely irrelevant, written off. And as the Feb. 1 Iowa caucuses approached, Rubio began to gather momentum. That was both bad for Bush strategically and difficult for him to swallow, given the way he had nurtured and cultivated Rubio as a young leader in Florida.

“Jeb was Marco before Marco was Marco. That’s why Marco is his protégé. Marco is Jeb’s son,” said Alex Castellanos, a Cuban-born Republican operative who knows the Florida political scene well. “And that’s what has to make this so difficult.”

Bush in his announcement speech last summer threw shade at Rubio when he said that as a governor there was no “no blending into the legislative crowd or filing an amendment and calling that success.” But it was the millions of dollars in attack ads on Rubio by the super-PAC supporting Bush — Right to Rise — that drew howls of protest from many inside the Republican Party, including even some contributors to the group who felt they were damaging to whoever emerged as the nominee.

“The super-PAC donors are squealing hard on that,” said the former Bush White House official.

Bush performed badly in Iowa, coming in sixth despite $15 million spent on his behalf on ads alone. Rubio finished a strong third behind Cruz and Trump. And now, Bush was facing a potentially embarrassing loss in New Hampshire and an avalanche of questions about whether he would drop out.

As he campaigned in New Hampshire over the past week, he showed signs of improvement as a candidate.

However, Bush’s shortcomings as a campaigner were still in evidence, despite the absence of any major gaffes. He missed several moments in which he could have connected personally with voters, a weakness made all the more apparent when studied in contrast to the personable town hall meeting styles of Ohio Gov. John Kasich and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie.

As the press prepared its obituaries for Bush’s candidacy, the debate on the campus of Saint Anselm College Saturday night changed the race and cut off any move within the establishment wing to rush toward Rubio. Suddenly, the governors’ argument that experience matters gained a new hearing.

And among the governors, Christie is out; Kasich — despite his strong second-place finish in New Hampshire — is hanging on financially by a string; and Bush looks likely to be the last left. He must now win over potential supporters, but he has a window: Cruz and Trump will battle each other in South Carolina, and Rubio is struggling to recover.

Rubio appeared liberated Tuesday night when he appeared before supporters and took full responsibility for his weak debate performance and finish in the New Hampshire voting.

“Our disappointment tonight is not on you, it’s on me. It is on me. I did not do well on Saturday night. Listen to this: That will never happen again. That will never happen again,” Rubio said. His vow produced a roar from the audience and also raised the stakes enormously for the next Republican debate this coming Saturday in South Carolina.

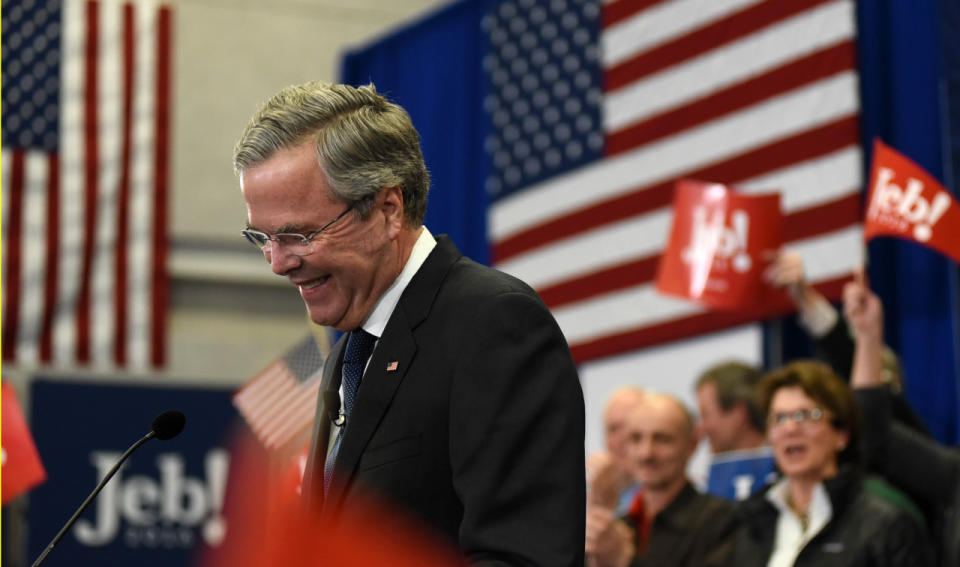

Bush’s primary night speech was adequate but lacked any real rhetorical or emotional highlights.

After the New Hampshire primary: Gov. Chris Christie is out; Gov. John Kasich is hanging on financially. Bush could be the last governor standing. (Photo: Faith Ninivaggi/Reuters)

“We need someone who believes in the goodness and greatness of the American people,” Bush said. “You’ve given me the chance now to go to South Carolina, where we are going to do really well.”

His finish in the Granite State was further overshadowed by the fact that Bush’s campaign and his super-PAC spent $36 million to win 11 percent of the vote while Cruz spent only about $600,000 and took home a few more thousand votes than Bush did.

South Carolina will now be a new test of whether Bush has indeed learned how to step up his game as a candidate — on the stump, in interviews and on the debate stage. Christie’s exit will leave a vacuum on the debate stage, and Bush has not yet demonstrated that he can effectively confront either Rubio or Trump.

But the Palmetto State is friendly territory for Bush. His brother, George W. Bush, won the state’s primary in 2000 and will campaign with him this week. And Graham said he will seek to make the contest “a referendum on commander in chief.”

“We have more veterans per capita than any state in the nation, and we have a lot of defense infrastructure, and I’m gonna talk about commander in chief and who’s best ready for that job. It’s sure as hell not Donald Trump,” Graham said.

And one friend of Bush’s who has spent time with him over the course of the campaign said the former governor has gotten better at many aspects of how to be a modern candidate and will continue to do so, because he has been forced to.

“Being on your death bed concentrates your attention,” said one Bush friend. “Am I gonna get up and fight, or was this all just a big waste of time?”