As Rubio stumbles, mining his memoir for clues

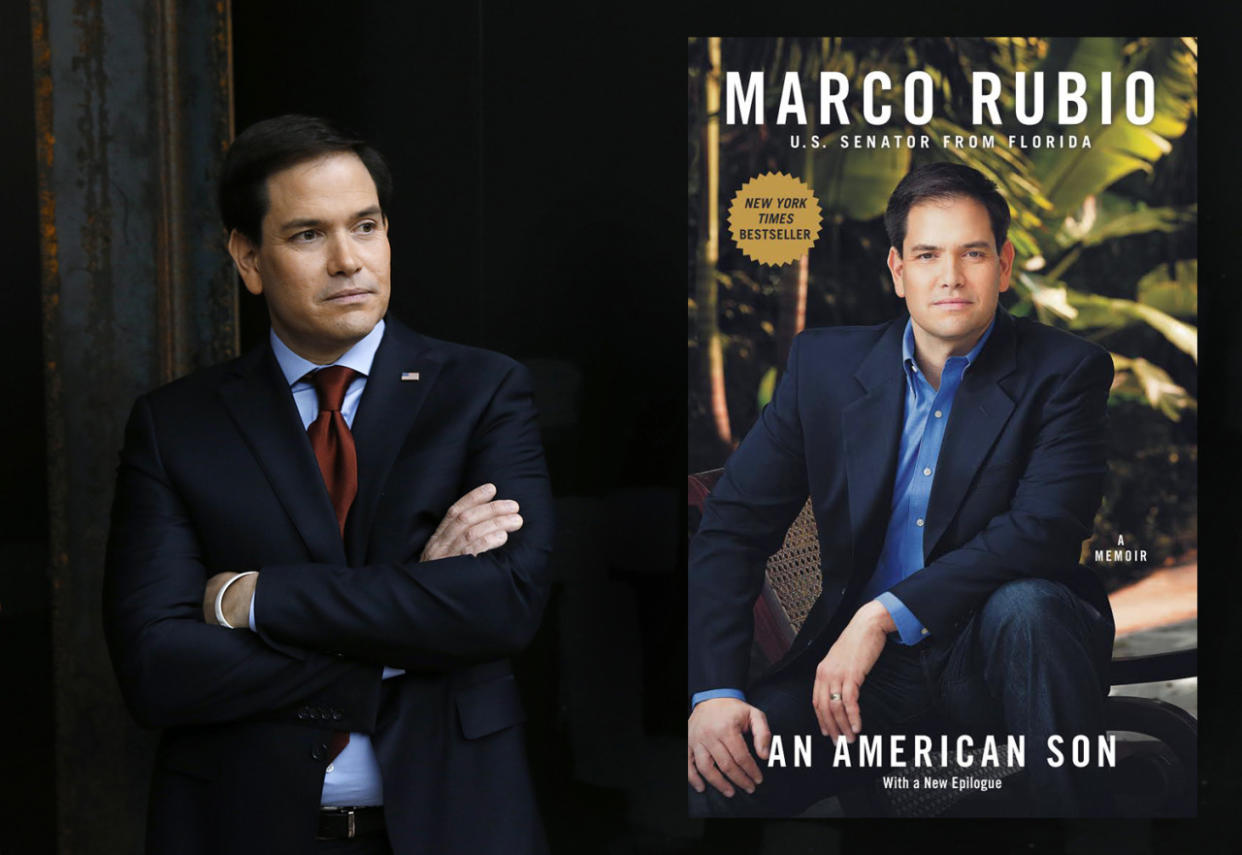

Marco Rubio waits to speak at an Iowa caucus site on Feb. 1; his book, “An American Son.” (Photos: Paul Sancya/AP and Penguin Publishing)

Long before Marco Rubio emerged as someone to watch in the Republican primaries this year, he saw himself as a man of destiny — someone who, after 18 months as a senator, following a few years as a local and state official in Florida, decided his life story merited an autobiography. His memoir, “An American Son,” can shed light on how Rubio sees himself and his career, at a time when his personality and temperament are coming under increasing scrutiny from voters and rivals.

The title is revealing: Rubio, with his soft good looks and ingratiating smile, has cornered the market on “boyishness” in this presidential race. At 44, he is the youngest candidate; Ted Cruz, whose brand is “bitterness,” is a year older, but seems to belong almost to another generation. And it reflects Rubio’s lifelong view of politics as personal or, more accurately, familial. He introduced himself to the country last year with a minutelong commercial that was almost entirely about his father’s job as a hotel bartender, the only work he could find as an immigrant from Cuba. The concept is that Rubio’s success will redeem the sacrifices of his parents, and by extension the extended community of Cuban exiles, whose dreams of success, for themselves and their children, he embodies. In the winter of 1998, campaigning among the Cuban-American immigrants of West Miami, Fla., “I discovered who I was,” he wrote. “I was an heir to two generations of unfulfilled dreams.”

This distinctive take on American exceptionalism is a theme he returns to over and over in speeches and debates — and in his book, which mentions his father’s job, on average, approximately every 10 pages. The attack Rubio endured in Saturday night’s debate, that his rhetoric (and by implication his mind) is stuck in a groove, finds little to refute it in “American Son.” Nor will the book dispel the picture his rivals have been painting of him, as a callow first-term senator who has built his reputation less on achievement than on his biography — actually, his father’s biography.

The book concedes that for most of his life he portrayed his parents as refugees fleeing Castro’s Cuba, living symbols of resistance to communism. In fact, as he now acknowledges, they emigrated from Cuba in 1956, years before the revolution, something that became known to the public only in 2011. Given Rubio’s account of how, even as a child, he immersed himself in the romantic, heroic saga of his extended family, it becomes hard to credit his assertion that this rather large detail could have escaped his notice all those years.

Slideshow: The battle for New Hampshire >>>

Rubio absorbed his political views from his beloved grandfather — who like most Cuban-Americans of his generation was strongly anti-communist and pro-Reagan — and he has carried those attitudes with him down to the present day. But the militant conservatism that has informed his candidacy is curiously absent from “An American Son.” As Rubio reminded voters in the recent debate, he is passionately opposed to abortion, under any circumstances. But in his book, abortion is mentioned exactly once, not as a moral question, but as a political issue confronting then-Gov. Charlie Crist, his rival in his 2010 Senate race.

“An American Son” repeats the standard Republican anti-Obama talking points, and he has also written a book of conservative policy boilerplate, “American Dreams: Restoring Economic Opportunity for Everyone.” But nothing in Rubio’s memoir suggests that he was driven by conservative ideology, contrasted, say, to Cruz. According to Cruz’s own memoir, “A Time for Truth,” the highlight of his high school years was joining a club called the Constitutional Corroborators, consisting of “five high school students who spent hundreds of hours studying the U.S. Constitution.” Rubio, by his own account, was consumed by dreams of playing for the Miami Dolphins. To put a number on it, the word “conservative” appears in 137 places in Cruz’s book, while Rubio uses it only 67 times — slightly less than the 74 appearances of “football.”

SLIDESHOW: The 8th GOP debate >>>

An indifferent student, Rubio buckled down to study law once it became clear to him that a football career wasn’t in the cards. He began his political career knocking on doors for a local congressional campaign, meeting “people who would be of invaluable assistance to me someday.” That neatly sums up Rubio’s account of his early career, which revolves almost entirely around political process and tactics — which mentor to cultivate, what job to run for, how to outmaneuver rivals. Whereas Cruz’s book is an extended exercise in score-settling, seething with resentments going back at least to his freshman year of college, Rubio seems careful not to alienate anyone, with the exception of Crist, who is out of office and clearly can be of no further use to his career. (If he were writing today, Rubio might want to revise some of his effusive praise for his onetime mentor, now rival — for the moment — Jeb Bush.)

In a campaign that has been dominated by Donald Trump’s monumental self-regard, it has been possible to overlook the fact that Rubio was the same age as Trump, 41, when he decided his life was worthy of an autobiography. (John McCain’s memoir came out when he was 63, a war hero and long-serving congressman and senator. Barack Obama’s “Dreams From My Father” — arguably a different kind of memoir, albeit one that helped propel his political career, came out when he was 34.) Trump, as is well known, takes credit for every one of his fabulous successes in life, but Rubio is far more modest. Throughout his life, faced with obstacles or setbacks, tempted to return to his humdrum life as a Miami real estate lawyer or to settle for an easy race for Florida attorney general rather than a seemingly unwinnable campaign for the Senate, Rubio would consult with his two most trusted advisers, God and his wife, Jeanette. And each time, the advice he got was the same: Go for it.

SLIDESHOW: The rise of Marco Rubio >>>

At times, in Rubio’s telling, God even put a finger on the scales. Rubio’s dark night of the soul came when his responsibilities as majority whip in the Florida House of Representatives led him to neglect his law practice, to the point where he had to sell his car and move in with his mother-in-law. Confronting the awful possibility that he might have to give up his political career, he stopped at a Catholic church to pray for guidance — which came literally minutes later, when his cellphone rang with a better-paying job offer that would not interfere with his political advancement. “I had just been on my knees asking God’s help,” Rubio wrote. “Now a door suddenly appeared to open and offer me a way out of my predicament. Was it a miracle? I don’t know.”

But in retrospect, it must have been at that moment, weighing the possibility that his career in the Florida Legislature was a matter of divine concern, that Rubio embarked on the path that led him to where he is today. As recently as four years ago, he ended his book on a poignant note of regret for all the time he had missed with his wife and four young children while pursuing his career. He had come to understand, he wrote, that “the mark I make in this world will not be decided by how much money I make or how many titles I attain. Rather, the greatest mark I can leave is the one I will make as a father and husband.” How did he go in a few years from there to embarking on the grueling, nonstop grind of a presidential campaign? That’s what men of destiny do.

Cover tile photo: Matt Rourke/AP