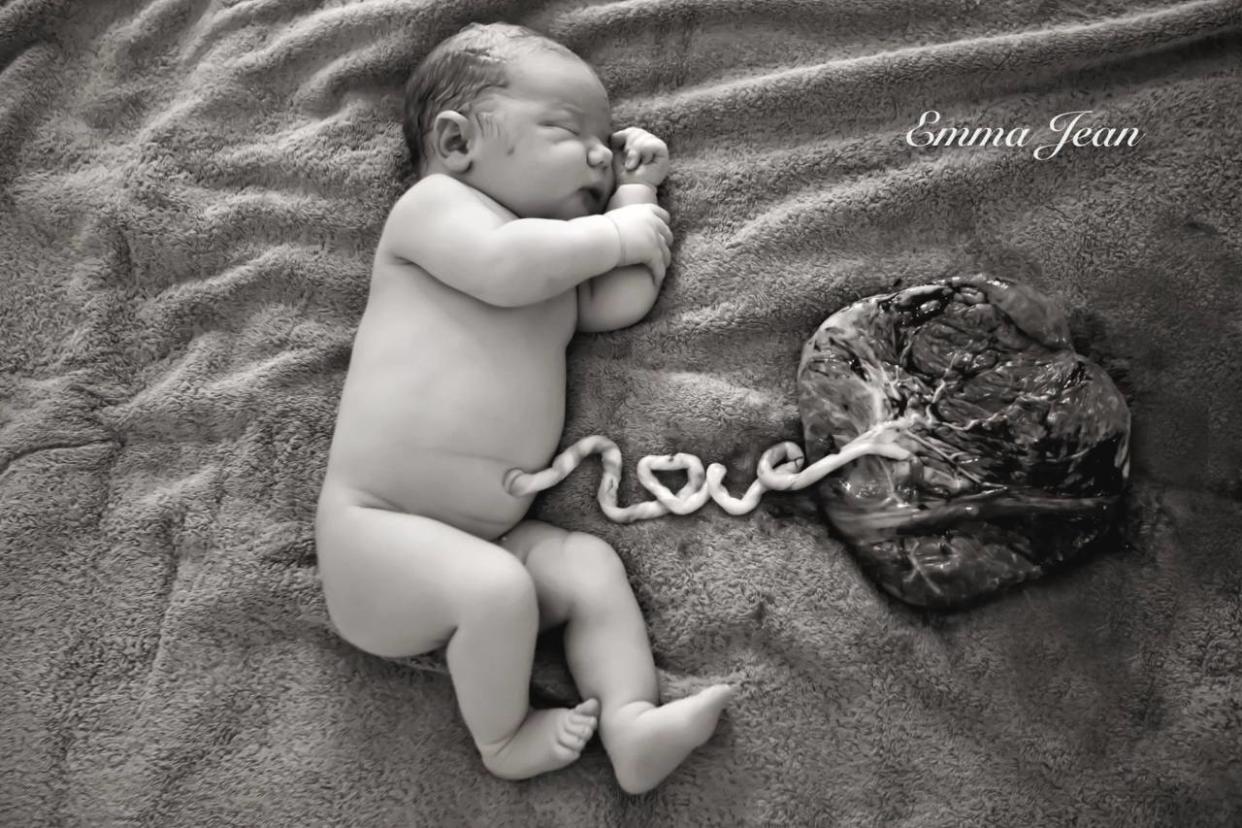

Striking Photo Shows Newborn With Umbilical Cord That Spells ‘Love’

A photo of a newborn that has been posted to Facebook is going viral thanks to the baby’s unique attachment — to his umbilical cord, which has been formed into the word love as it leads to his placenta, which lies on a towel beside him.

“Welcome earthside sweet little Harper,” reads the caption to the image, above, taken by professional photographer Emma Jean, seemingly based in Australia, who posted it to Facebook on Jan. 2. It has since been liked more than 4,400 times and shared more than 1,000. It goes on to explain that “as a Maori baby his placenta will now be returned to the land,” meaning it will be buried in the earth, according to the tradition of the indigenous people of New Zealand. She concludes the post by asking, “How will you honor your placenta?”

Story: Kim K. on Eating Placenta: ‘What Do I Have to Lose?’

Responses on Facebook have been leaning toward the supportive and intrigued, with the 500-plus commenters using words like beautiful and amazing to describe the image. Many shared that they had also buried their placentas, sometimes topping the soil with newly planted tree, while others said that they had gotten it freeze-dried and encapsulated for ingestion — a nutritional trend that’s been growing in natural-birth (and some celebrity) circles — or simply photographed it. Some admitted the Facebook image had changed their initial thoughts about placentas. “By never looking at it, it made me nauseous to even think of it. Although reading these comments and reading what was done with many of them is quite beautiful,” noted one former skeptic.

Story: Women Told to Avoid Birth in Hospitals in U.K.

The idea of placenta honoring has strong roots in some cultures of Bolivia, Sumatra, Uganda, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Ghana. According to Jodi Selander, the self-dubbed “Placenta Lady,” who runs a placenta-encapsulation business in Las Vegas, ancient Egyptians believed in duality of the souls — one inhabited by the body, the other by the placenta. “The placenta even had its own hieroglyph, which looked like a crosscut section of a human placenta,” she writes on her website. “In royal processions, a high-ranking official would carry a standard representing the placenta.”

Such ideas can seem foreign to women living in the U.S., where it’s only within the past decade or so that trends of ingesting or planting one’s placenta — or doing anything with it beyond regarding it as medical waste not worthy of a glance — have begun to take even a slight hold.

“I think when women began delivering babies in hospitals, they moved from viewing birth as a primal, powerful event to a sterilized, medically managed process and wanting everything to be neat, clean, and tidy,” Selander, who has become somewhat of a placenta expert since starting her business in 2006, tells Yahoo Parenting. “You have to go back quite a ways to see where we detached from celebrating birth’s messy glory and moved to not wanting to even see the byproducts.”

While many Native American tribes have placenta-based rituals, she adds, “It’s a cultural thing that Western women don’t want to see it.” And despite a brief reclamation of natural-birth messiness in the 1970s, she says, “it’s definitely a new thing” that more and more American women have begun to think about what they’d like to do with their afterbirths — much of that tied into the growing home-birth movement.

That’s been largely born out of necessity, Selander explains, as many times women are not permitted to bring their placentas home from hospitals. While three states (Hawaii, Oregon, and Texas) expressly permit the practice, and no state has a law forbidding it, “it’s strictly hospital policy” that may cause roadblocks for women. “But through education and outreach to hospitals across the country, I’ve been able to help moms get their placentas released and have sometimes been able to change hospital policy,” she says. Having a policy against it, she notes, is kind of a “knee-jerk” reaction based on a hospital’s health-risk concerns.

Besides wanting to save a placenta to be freeze-dried and encapsulated for ingestion — something that has been anecdotally tied to health benefits including increased energy and decreased postpartum depression — Selander says that many women want to bury their afterbirth, often planting a tree or shrub on top of it. Alternately, “since we’re often no longer tied to our land,” or live in city apartments or places with arid soil (like the desert where Selander is based), she suggests that parents who want to do something special with a placenta but aren’t up for ingesting try getting it dehydrated and then scattering the remains somewhere special, “kind of like you’d do after a cremation,” she says. “Or they can keep it.”

As for why honoring or even celebrating one’s placenta is meaningful, Selander has a passionate yet basic explanation. “We keep baby teeth, hair, other mementos. … I think we should encourage that connection,” she says. “[A placenta] is not terribly attractive to a lot of people, so it gets kind of a bum rap. But without the placenta, there wouldn’t be a baby. It’s the life force. I think it should be at least acknowledged.”

Please follow @YahooParenting on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, andPinterest. Have an interesting story to share about your family? Email us at YParenting (at) Yahoo.com.