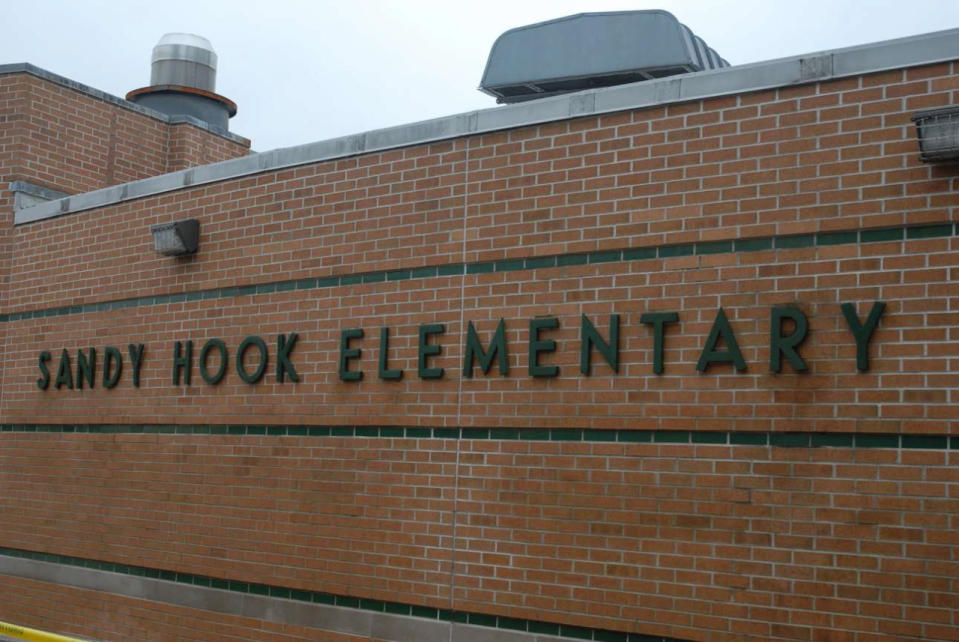

How One Sandy Hook Survivor Is Moving Forward 3 Years Later

Kaitlin Roig-DeBellis had just sat her first-graders down for a morning meeting at Sandy Hook Elementary School on Dec. 14, 2012, when the gunshots rang out. Twenty-year-old Adam Lanza had forced his way into the Newtown, Connecticut school and had begun firing. Roig-DeBellis ushered her 15 students into a tiny bathroom in the back of their classroom and barricaded the door, keeping her kids calm and quiet while Lanza started killing people in the classroom next door, eventually shooting himself to death as police descended. Twenty first-graders and six adults were slain at Sandy Hook Elementary School that day.

STORY: Life After the Sandy Hook School Shooting

Roig-DeBellis was hailed as a hero for her quick thinking, which saved her students’ lives. Almost three years after the tragedy, one of the worst mass shootings in the nation’s history, the former elementary school teacher is focusing on the future. Her memoir, Choosing Hope: Moving Forward From Life’s Darkest Hours, recounts the pain and suffering she endured following the shooting and how she fought to regain control of her life. In an exclusive interview with Yahoo Parenting, Roig-DeBellis shares the importance of moving forward every day, even if one can never move on.

Yahoo Parenting: What’s the most troubling image you still carry with you from that day?

Kaitlin Roig-DeBellis: Thankfully, I didn’t see anything on that day in terms of the horror. It was what we heard. It sounded like the goriest movie you could imagine. It was just so loud, so scary, and it’s so hard to explain to people that this was right next to us — just on the other side of a wall. We were so close to the gunman that day, it sounded like we were on a battlefield. What I carry with me is just how close we came to not making it out of that bathroom.

STORY: When a Child Dies, and Another Is Born

What was it like getting your students into the bathroom?

When the shooting began, I knew immediately what it was so I got up, turned out the lights, and closed the door. My keys were on my desk on the other side of the classroom, so there was no time to lock the door. I turned around and told the kids we needed to get in the bathroom right now. Understandably they looked at me funny and said, “What do you mean?” I just repeated myself with the same firmness and seriousness. They could hear the gunshots too; they knew something was really wrong, so we began piling in. The bathroom was about 3 feet by 4 feet with a toilet in the middle. Looking back I have no idea how we all got in there. There was a storage cabinet right by the bathroom on wheels so I wheeled it in front of the door, closed and locked the door, and kept the light on and just waited. I’ll never know if the gunman came into our room, but I imagine he did. We were the first classroom he walked past.

You wrote about having a lot of anxiety being in public places after the shooting — has that gotten better?

If I go to a restaurant, I have to sit where I can see the door. I have to know where the exits are at all times. But really, it’s unexpected loud noises that still shake me — a door slamming, cars or trucks outside on the street. I don’t think that will ever go away.

You say Choosing Hope is not for people who want to hear about the “gory, gruesome” details of the day — and that the chapter about the shooting is “optional.” Who is the book for?

I wrote this book because when I was out sharing my story, people came up to me in droves telling me about their issues —they were diagnosed with cancer or their son committed suicide. They told me they were grateful they’d heard my perspective that the things that happen to us don’t have to define us. That we can make a choice to move forward from whatever that really hard time is, with purpose. I realized sharing my pain was enabling others to get through theirs, and that was really powerful for my own healing.

Was there a rock-bottom moment after the shooting when you said, “I need to move forward?”

After Dec. 14, my sense of safety and security were gone. I was a complete shell of myself. I couldn’t go anywhere. I was walking around in a daze trying to answer the whys. Why our school? Why my fellow educators? Why those little babies? It was like I was beating my head against the wall, and then it just occurred to me that I’m never going to have an answer. Not then, not now, not ever. For many of us, especially during really hard times, we spend so much time focusing on the questions we can never answer and we forget that there are so many we can. And there is power in that. My healing began the day I shifted my focus to questions I could answer. For me, there were two: How do I make sure that this day does not define my students or me? And how do we get our control back?

You started your nonprofit Classes4Classes — a social network that enables K-8 classes to give educational gifts to students in need — as a way to teach empathy and kindness. How does it work?

Kids are told to be kind and empathetic, but we want students to be actively engaged by doing for others, not just talking about it. When teachers register their classes with us — either as a giving class or a receiving class — they get a profile page and are then linked to another class in our network. We’re helping students help other classrooms in need but also giving them a platform to showcase their work within the social curriculum — kindness, compassion, and empathy. Above all, we are a great resource. I get how busy teachers are — Classes4Classes is there to assist with the things they’re already teaching, and we’re crowdfunded so there’s no fundraising component.

You’ve done a lot of big things to honor the lives lost at Sandy Hook. Are there any little ways you honor them?

Their memories, their lives, are on my mind 24/7. I have this very real awareness that it could have easily been my kids and me who died that day. Every day I think about how I have to live my life with purpose because I would want someone to do that if it had been us. I have to put one foot in front of the other, even on the hard days, because if I just crumbled, what good would that be?

How do you stop your mind from wandering back to that day?

I think a lot of people feel like when they have something bad happen, they have to bury it, they have to move on, but you have to allow yourself to have those feelings, good and bad. Just a few weeks ago I went back and read all the unopened emails that were still sitting in my inbox from Dec. 14th. I had over 300 unread messages, and I knew what they were but never wanted to open them. It was friends telling me how brave I was, that they were glad I was OK, asking what they could do. I just sat there and cried, hysterically, as I read. Even three years later, it’s important to allow yourself to have those cries. I will never move on from Dec. 14th — it is part of me and it always will be — but every single day of my life I will move forward.

What do you hope people will get from reading this book?

I hope it will enable anyone who has gone through dark times to know that they can find the light. We all have them — and knowing that you are not alone can help you realize that you can come out on the other side. Pain that seems insurmountable doesn’t have to be. We can’t be defined by evil if we’re choosing kindness, compassion, empathy, and hope. It’s just not possible.

(Photo of Kaitlin Roig-DeBellis: Peggy Sirotta)

(Photos: Getty Images)

Please follow @YahooParenting on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest. Have an interesting story to share about your family? Email us at YParenting (at) Yahoo.com.