You’ve probably never heard the story of the best pitching performance in Mets history

After a hot start and disappointing second half to his rookie campaign, Ron Swoboda was frustrated to be called out looking to the end the first inning. It was the penultimate day of the Mets’ disastrous season and he’d just squandered a first-and-third scoring opportunity. Swoboda disagreed with the call and he said so. Then he said it some more. There was nothing profane about his grousing but even as he walked back to the dugout, he just wouldn’t quit it. So home plate umpire Lee Weyer tossed him from the game.

Swoboda’s parents were in the stands that day, having driven up from Baltimore. And so, after hitting the showers, the newly 21-year-old outfielder met up with his folks and went to get some dinner.

Probably the family went to Lum’s on Main Street in Flushing. They went there a lot when Swoboda played in Queens. His grandfather was a Cantonese cook and George Lum made the best Cantonese food they could find close to Shea.

Hours later, they emerged from dinner and Swoboda noticed something troubling: The lights were still on at the stadium.

“I thought ‘Uh oh. What does that mean?’” Swoboda told Yahoo Sports.

“I found out the next day two things. I found out Rob Gardner went 15 innings, and I wasn’t supposed to leave.”

Two days, four games, 49 innings

On October 2, 1965, the New York Mets and Philadelphia Phillies played two baseball games totaling 27 innings. The following day they would play another two baseball games totaling 22 innings. That was the final weekend of a disappointing year for both teams. Come Monday, the 1965 season would be over — the Phillies having finished sixth in the 10-team National League and the Mets dead last.

All told, there were 49 innings of completely meaningless baseball played that weekend. Buried in the middle was a historically dominant pitching performance by a 20-year-old rookie making his fourth big league start. It was the high point of his career. ESPN recently noted that, statistically speaking, it is the best pitching performance in Mets’ history. You’ve probably never heard of him.

And perhaps strangest of all: Not only did his heroic effort not matter in terms of the season or the standings, the game he pitched doesn't even show up in the Mets’ final record. It was barely mentioned in the next day’s newspapers — all the beat writers were on strike.

Rob Gardner threw 15 scoreless innings for which he received a no decision in a non game. The whole thing was redone the next day starting from scratch. The Mets lost, but by then Gardner was already on his way home.

“Sounds like I really went down in history,” he told Yahoo Sports, almost 55 years later.

Trading zeros

The Friday night game was rained out. Normal enough. For some reason lost to history, rather than play a day-night doubleheader on Saturday, the makeup was scheduled as a twi-night doubleheader. This would prove to be inopportune.

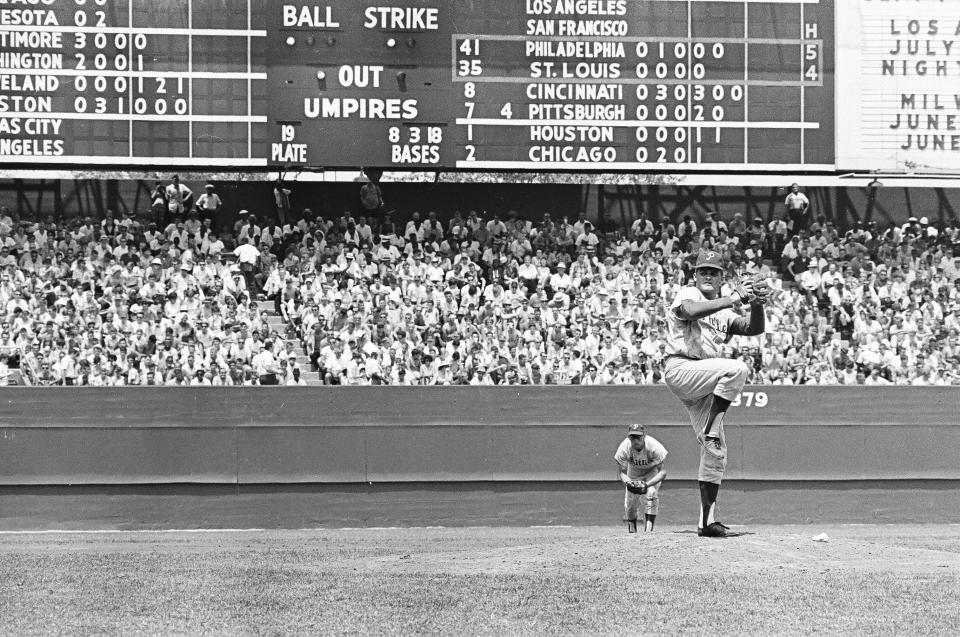

The Phillies cruised to a 6-0 victory in the first nine innings played that afternoon. Then, while the Dodgers clinched a National League pennant behind Sandy Koufax in front of 41,574 in Los Angeles, Gardner took the mound at Shea Stadium to try to salvage a net neutral day in New York. A crowd of 10,371 looked on.

It was the last chance that year for Gardner — a September call-up who entered the day with a 6.92 ERA over 13 ill-fated innings — to prove he deserved a chance to crack the 1966 rotation. He was nervous. Everybody else just wanted the season to be over so they could go home.

Inning after inning, Gardner and Phillies starter Chris Short traded zeros. For a while, at least, it was something of a breeze — no stakes and few baserunners. The Phillies batters made it easy on Gardner, swinging at first pitches that turned into quick outs and kept his pitch count low — not that anyone kept track of such a thing at the time.

The Mets stranded two in the bottom of the ninth. It was their last best chance to split the doubleheader and send Gardner home for the offseason with his first big league win.

Instead, they went to extras. The Mets weren’t all that worried about their rookie’s arm and he wasn’t either. Pitchers threw complete games back then. You went out there knowing relief wasn’t coming. Besides, as an 18-year-old in the Florida State League, Gardner had once gone 16 innings, and look where that landed him.

Across the diamond, the Phillies started thinking about taking Short out. He was a little older, and had worked harder with more strikeouts to that point. He’d done well, but it wasn’t like they were playing for anything anyway. Maybe it was time to call it a night.

Gardner later heard that when Philadelphia tried to pull Short from the game he said, “I’m not coming out until that other son of a bitch comes out.”

In the box score, Gardner’s top of the 14th went smoothly — a no-nonsense one-two-three inning. He was sure he’d lost the game, however, when Phillies third baseman Dick Allen, who would go on to bat .588 in his career against him, crushed a ball to dead center. Back and back Cleon Jones went until, standing on the warning track, up against the 410-foot marker — or at least that’s how the version of the story that got remembered goes — he caught the ball for the second out of the 14th. By that time, Allen had rounded first and was halfway to second base on his premature home run trot. As he cut across the mound on his way back to the dugout, he looked at Gardner, who just shrugged. Allen could only laugh.

Gardner pitched one more inning before being pulled for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the 15th. True to his word, Short matched him frame-for-frame, leaving the game after the inning was over. In all the years of baseball since then, only three times has a pitcher gone 15 or more innings. Only once has it been scoreless. And on October 2, 1965, two pitchers did it in the same game that no one was paying any attention to.

“I have to point this out, the guy that pitched against me pitched equally if not better than I did.” Gardner said, looking back. “He just didn’t live long enough to be interviewed about it.”

Three scoreless bullpen innings later, the game was suspended just before the city’s 12:50 a.m. curfew. All told, the whole thing took four hours and 29 minutes. It was recorded as a tie.

Suspended reality

Nowadays, a suspended game is picked up wherever it leaves off. This creates quirks, like the 12-minute resumption that the Red Sox and Royals played last year. But back in ‘65, the rules were such that a suspended game was declared a tie and played again in its entirety.

With only one day left in the season, that meant another doubleheader after a late night. Neither basement-dwelling team was especially interested in dragging out their misery much longer, and the umpires’ crew chief, Frank Secory, even called National League President Warren Giles to request an exemption from the rule requiring them to make up the game — but none was granted.

And so, a mere 12 hours after the game ended in a tie, the two teams took it from the top.

(The turnaround nearly deprived Sunday’s game of a two-person broadcast booth. Lindsey Nelson called college football on Saturdays, and Ralph Kiner called Jets games on Sundays — alternating who partnered with Bob Murphy in the Mets booth. Nelson had no idea that Saturday’s game was being replayed as part of a doubleheader on Sunday and nearly missed the first pitch, which is an incredible testament to an era where an 18-inning game could end in a tie and even one of the team’s broadcasters wouldn’t find out until the following day.)

Since there was no chance of him pitching on that final day of the season, Gardner and his new wife packed up their room at the Traveler’s Motel, where he had stayed during his cup of coffee, and hit the road home to Binghamton, New York. That offseason, he would work at a hotel drumming up business clientele, and answer well-meaning prying questions from friends and family about what it was really like to be a big league baseball player. They listened to the game on the drive home, but they must not have been paying very close attention.

‘It’s about relevance’

Rob Gardner, now 75 and speaking to me from his home in Florida, didn’t realize the game hadn’t counted. He knew it was tied when the night ended, but spent the past 55 years assuming that the next morning, in his absence, they had picked up right where his impressive record-setting pitching performance had left off.

They hadn’t. I was the bearer of the bad news. And in a weird way, this, more than the knowledge that the Mets went on to lose the game anyway, felt like it erased his accomplishments.

“That means that game never existed,” Gardner mused.

Which isn’t quite true. The individual stats still counted. Ties were an accepted part of the baseball season back then. But no, the 15 scoreless innings he tossed that night are not reflected anywhere in the Mets’ final record from that season, which still added up to 162. Not even in the losses.

I asked him how it felt to learn this now.

“Disappointed, yes,” he said. “Mad, no. That's too far in the past to be mad about it. But I’m kind of sad, yeah. All for naught.”

Gardner never came close to that kind of performance again. And he rarely had the chance. By the middle of the following year, the soft-tossing lefty was moved to the bullpen.

“That wasn’t a good place for him. He was a guy that needed to see the whole lineup a few times. He’s a feel pitcher. Obviously the guy had some pretty good stamina,” said Ron Swoboda.

After short stints with five other teams that never really clicked, Gardner retired from the sport after the ‘73 season and went back to Binghamton for more than just the winter. There he became a firefighter paramedic, and it’s funny that people call him up all these years later to ask about a baseball game, because he’s since learned an important lesson in perspective.

“It’s about relevance,” Gardner said. And then he explained that on September 11, 2001, he and five other medics drove their ambulance down to the city and into Ground Zero to see if they could help New York’s first responders.

“We were only there 24 hours and we weren't even supposed to dig, we were just supposed to stand around, but every one of us got involved, in some corner helping somebody dig for something. I mean when you think about an entire truck being buried two stories underneath your feet, along with the people that came with it. Yeah, I mean there's relevance there. I felt a lot more relevant as a firefighter than I did as a baseball player.”

‘I don’t know why I want to see it’

Gardner doesn’t watch baseball anymore, but he had hoped this story would lead me to find footage of the game, which he had never seen before.

“I don’t know why I want to see it,” he said. “It was pretty boring, I mean nothing to nothing is pretty boring.”

Unfortunately, it’s not one of the games Major League Baseball has archived. That, combined with the lack of contemporary stories from the newspaper strike and the limited surviving primary sources, makes it difficult to even recreate the subtleties of that day. What survives is a set of two opposing facts: that it was a record, that it was rendered immediately and uniquely immaterial.

In 1965, the @Mets and @Phillies played an 18 inning scoreless tie at Shea Stadium. Mets starter Rob Gardner pitched 15 scoreless innings, allowing just five hits. It was New York's second tie of the season: https://t.co/VUvNAGrbBd pic.twitter.com/wLA21gvHfP

— Mets Rewind (@metsrewind) June 20, 2019

It’s an extreme manifestation of the dichotomy inherent in all baseball games. On a large enough scale, they are always meaningless except for the numbers they leave behind. But to the right people, those numbers evoke something more visceral.

Even now — when most Mets fans have forgotten his name and Gardner himself has forgotten many of the details from that day — the team’s broadcast will periodically quiz fans on a bit of trivia, challenging them to remember who holds the franchise record for scoreless innings in a single game.

And when that happens, one of Gardner’s friends, or maybe his son, will text him: “Your question came up again.”

Hannah Keyser is a reporter at Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email her at Hannah.Keyser@yahosports.com or reach out on Twitter at @HannahRKeyser.

More from Yahoo Sports: