Women’s professional sports grapple with eroding rights

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

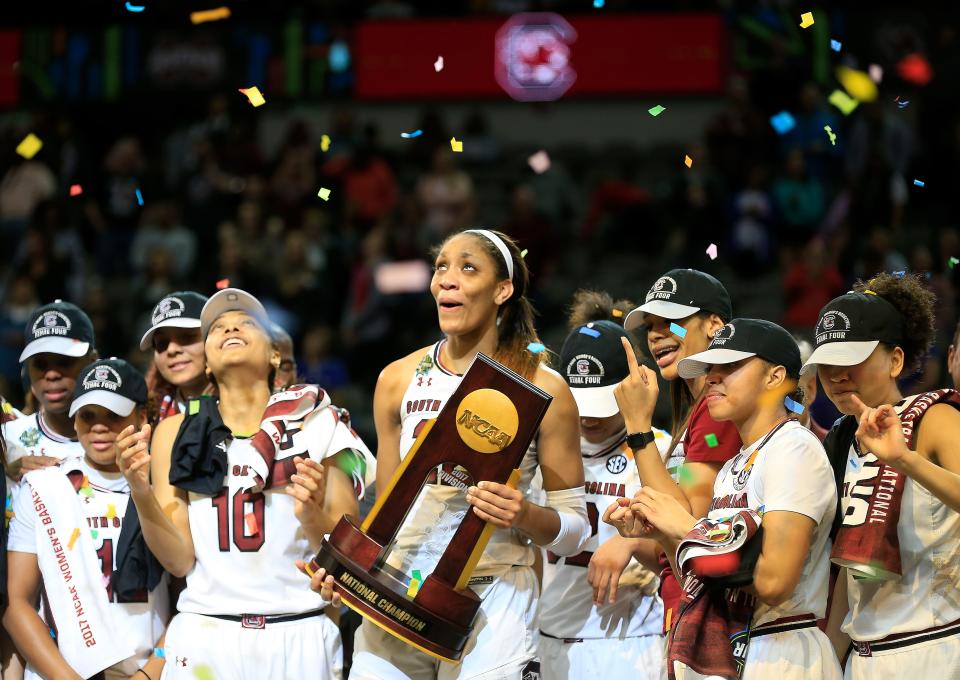

Shortly after leading South Carolina to its first-ever NCAA women’s basketball title and becoming the No. 1 pick in the 2018 WNBA draft, hometown star A'ja Wilson was honored with a statue outside Colonial Life Arena.

Now a two-time MVP with the Las Vegas Aces, Wilson is still considered royalty in Columbia, South Carolina – a city in a state where legal access to abortion has been under heavy assault following the Supreme Court’s June 24 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Asked whether she would still attend South Carolina given the current situation, Wilson said “probably”; with her family just 30 minutes down the road, she could have turned to them if she needed help.

But it would be a different story for her daughter.

“No, I would not let my child go there,” Wilson said without hesitation.

Athletes, abortion & anxiety: As rights erode, fear for future of women’s sports

This ongoing series is in response to the June 24 ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court case that granted women a constitutional right to an abortion. If you are a current or former athlete, coach or athletic administrator who wants to share your abortion story, please email narmour@usatoday.com or lschnell@usatoday.com.

It is a startling admission from one of this century’s most accomplished female athletes – but Wilson views it as her responsibility to use her platform to speak out on issues that impact women, even if what she says sends shockwaves through the sports world.

Following the Supreme Court's decision, about one-third of states banned or severely restricted abortion, impacting roughly 30 million women ages 15-49, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and policy organization. And more legislation is on the horizon.

USA TODAY Sports spoke to more than 30 current and retired professional female athletes, coaches, agents and sports executives to gauge how they’re weighing the new reality of a country where women’s rights are being challenged or stripped away.

The athletes spoke candidly and passionately about their fear and the uncertainty of a future without abortion access, particularly if they get traded to or drafted by a team in a red state.

“If people have to choose, I’m sure they’re not going to want to choose to go to places where they don’t have rights to their own bodies,” said Breanna Stewart, a perennial All-Star who plays for the WNBA’s Seattle Storm.

Nothing has changed but the date… gut-wrenching and disgusting with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of Title IX and yet today women wake up with less rights than they had before. Our bodies, our choice! pic.twitter.com/paffAH5V25

— Breanna Stewart (@breannastewart) June 24, 2022

Women made extraordinary strides following Title IX, the landmark equity in education law, and nowhere is that more apparent than on playing fields.

Prior to Title IX’s enactment in 1972, fewer than 300,000 high school girls and 32,000 women in college played sports, according to the National High School Sports Association and NCAA, respectively. Now, more than 3.4 million girls are playing high school sports and women make up almost 40% of NCAA athletes. There are professional women’s leagues in soccer and basketball, and women are the driving force for the success of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic teams.

But the gains of Title IX would be improbable if not for the Roe decision a year later.

In an amicus brief submitted during the Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization case that overturned Roe, more than 500 current and former women athletes said having control of their reproductive choices allowed them to make other choices, as well. Like, going to school on an athletic scholarship. Pushing their bodies beyond what they thought possible and realizing how strong they are. Experiencing a world beyond their hometown, or home country, on trips with an athletic team.

‘They’ve had 50 years to figure it out’: Despite progress driven by Title IX, colleges devote fewer resources to women’s sports

That news of Roe’s demise came a day after the 50th anniversary of Title IX made it particularly cruel for them. It also came during the middle of the U.S. outdoor track and field championships, an irony not lost on Kara Goucher, a two-time Olympian who now works as a distance running analyst for NBC.

“When I went to call those races, I was struck by all these amazing performances and I was thinking, and this makes me emotional,” Goucher told USA TODAY Sports, her voice catching, “I was thinking, fast-forward 10 years and some of these women won’t be here because they’ll be in a red state and they will get pregnant.

“They’ll never get to find out who they can be.”

‘No choice at all’

Studies show 1 in 4 women will have abortions by the time they are 45. Though it is widely known within women’s sports that abortions happen, athletes are leery of sharing their stories.

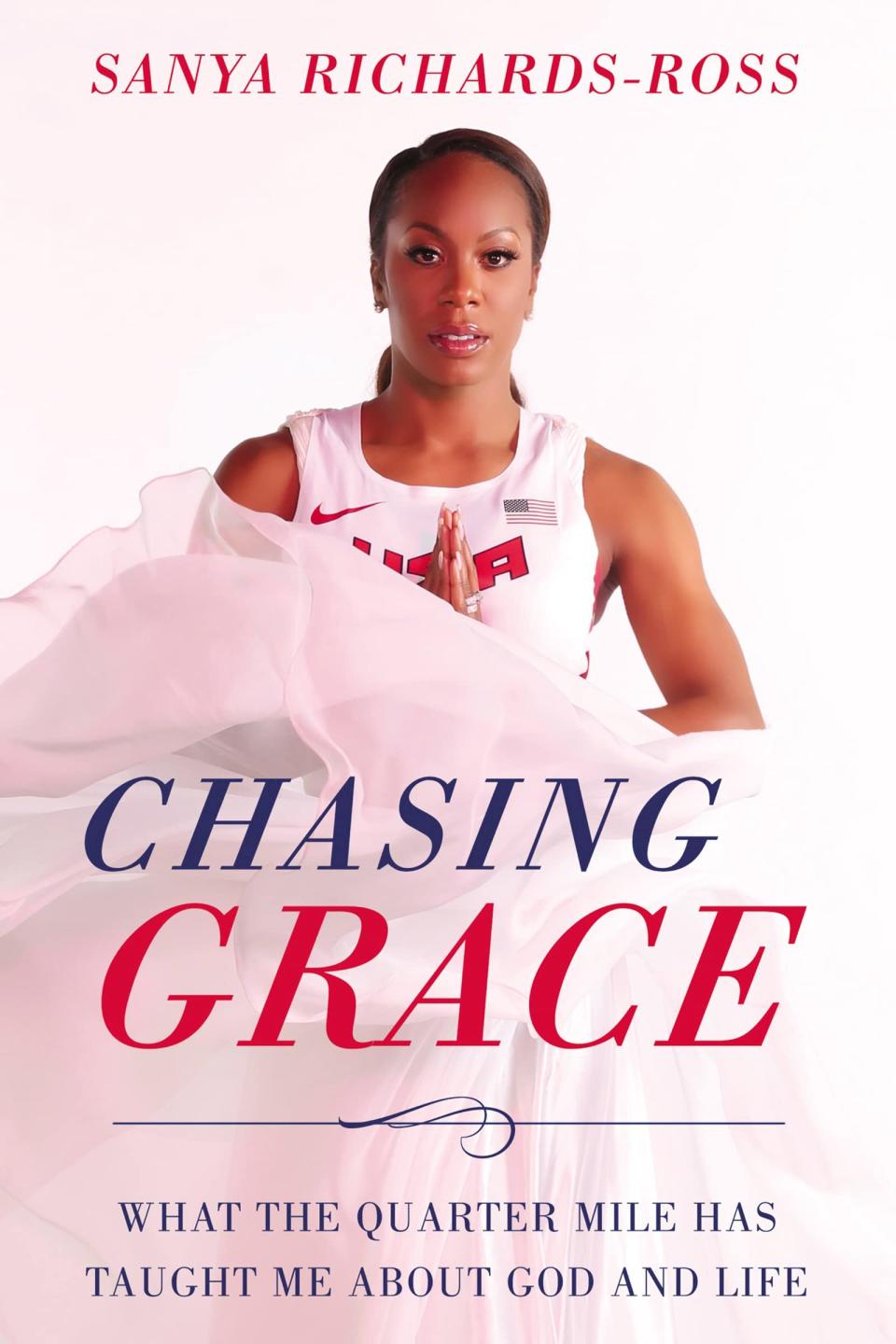

In 2017, Olympic sprinter Sanya Richards-Ross, who won five medals, including four golds, at two different Games, revealed in her memoir that she had an abortion two weeks before the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

“Everything I ever wanted seemed to be within reach,” she wrote. “The culmination of a lifetime of work was right before me. In that moment, it seemed like no choice at all.”

During a media blitz to promote her book, Richards-Ross told Sports Illustrated, “The truth is, it’s an issue that’s not really talked about, especially in sports, and a lot of young women have experienced this. I literally don’t know another female track-and-field athlete who hasn’t had an abortion.”

Though Richards-Ross later backed off that assertion, the curtain had already been lifted: Some women athletes at the height of their careers have abortions to keep competing at the highest levels. It is not merely about realizing dreams of winning championships, either; finances play a role. Should they take a year off to have a baby, their income could plummet – with no guarantee they’d ever be able to come back and perform, or earn, at the same level again.

In 2019, Allyson Felix revealed that Nike, her then-sponsor, offered her a contract valued 70% less than she previously enjoyed after she gave birth to her daughter. The company also declined to guarantee Felix wouldn’t be monetarily punished if she didn’t perform well shortly after giving birth.

“My body is my job,” said Gwen Berry, a two-time Olympian in the hammer throw. “My body is how I’m able to feed my family and provide for others. If I cannot decide what to do with my body, how am I going to compete? How am I going to pay my bills?”

Goucher said she is frustrated that while it takes two people to get pregnant, typically only the woman suffers the consequences when it’s unplanned – even if she’s in a committed relationship. Goucher pointed to Richards-Ross, who was engaged to NFL cornerback Aaron Ross when she found out she was pregnant weeks before she was “expected to deliver this gold medal for the United States.”

“What was she supposed to do? Was she supposed to not run?” Goucher said. “We would never ask someone to skip the Super Bowl because their wife just had a child … male athletes, they don’t even have to think about it, they just go and perform.”

But for women athletes, it’s a considerably more fraught situation.

After Roe v. Wade’s reversal: Uncertainty for college women’s coaches, athletic departments

The weight of judgment

For many elite women athletes, irregular menstrual cycles are a side effect of rigorous training. In some cases, it’s considered a badge of honor, a necessary sacrifice to compete at the highest levels.

But that also means a missed period wouldn’t necessarily alert an athlete that she might be pregnant. By the time she does realize it, her options could be limited, especially in states that severely restrict abortion.

“It happens with regular women, too!” said Shamier Little, who has competed for the United States in the 400-meter hurdles at three world championships. “I’ve seen how draining that can be mentally. To put some through that type of pain is just unfair.”

Abortion, though common in the U.S., is politically polarizing and carries a tremendous stigma, even within women’s sports, where many athletes quietly acknowledge it’s a frequent occurrence.

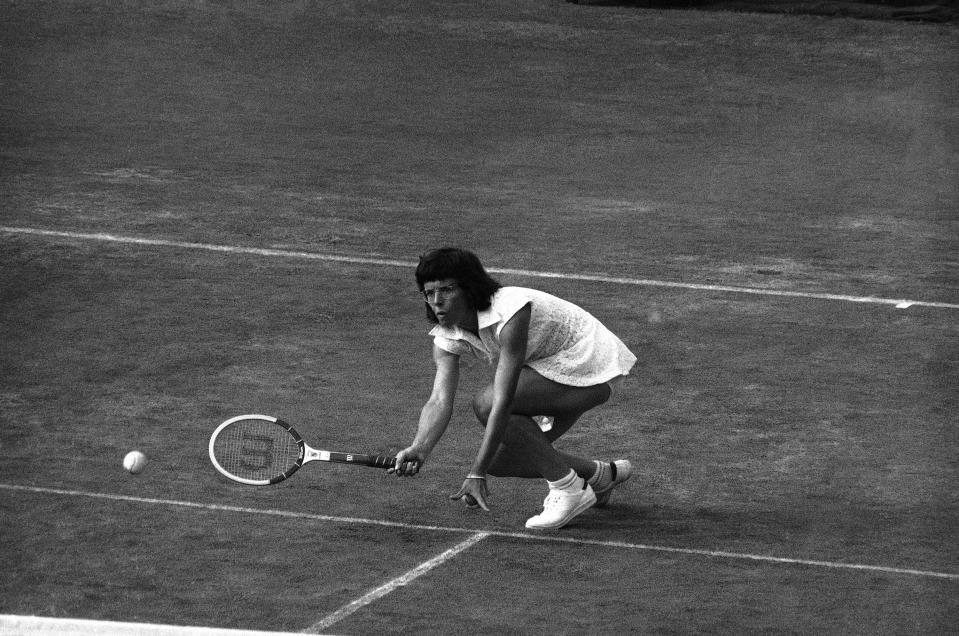

In 1971, when she was 27 and the top-ranked player in the world, tennis icon Billie Jean King unexpectedly became pregnant. She chose to have an abortion – legal in California years before it was legalized nationwide.

In order to obtain the abortion, King first had to explain to a hospital committee why it was necessary, and get a permission slip signed by her husband. In a Washington Post op-ed, she called going before the committee “one of the most degrading experiences of my life.”

Even athletes who take responsible measures to avoid unplanned pregnancy can feel the weight of judgment.

“This is a good time to own my truth. There was a point in college where I had to go get Plan B (the morning after pill),” Natasha Cloud, a guard with the Washington Mystics, told USA TODAY Sports, acknowledging she’d never before shared this story publicly. “It is what it is. I made a grown decision that was available to me at the time, and I’m so thankful, because I wouldn’t be sitting here today if I didn’t have that choice. I wasn’t prepared, at 19 years old, to have a child.”

Plan B is used after unprotected sex or when other forms of birth control – typically condoms – fail. Women take it to prevent ovulation, which prevents pregnancy.

In a concurring opinion to the Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that other legal precedents, including the right to obtain contraception, should also be reviewed, and potentially overturned. Many women now fear a future where even pregnancy prevention methods are unavailable.

“Absolutely. I think about it every day,” said Berry, who trains in Nashville while pursuing her master’s in public health at Tennessee State. “You are forcing me to make a decision that will change my life forever.

”It feels like we’re not even part of the conversation.”

Leagues supporting athletes

As support for the WNBA and NWSL explodes across the country, expansion for both leagues is expected by 2025, according to commissioners Cathy Engelbert and Jessica Berman, respectively.

Athletes who spoke with USA TODAY Sports understood the many considerations needed when deciding on expansion cities, but said they will make their voices heard if a franchise sets up shop in a market rolling back women’s rights.

“At the end of the day, it’s a business decision, and they’re going to do what makes the most money,” Wilson said. “They need to understand what women in the WNBA stand for, so it is something they need to look into.”

While acknowledging “we’re in a very diverse country, and a very divisive country,” Engelbert said there’s a variety of factors that go into expansion consideration. She referenced the WNBA’s past social justice work and said she thinks that “players want to use their voice to make an impact. They don’t want to run from a state necessarily.”

There’s also more immediate issues to consider before the expansion conversation.

A handful of NWSL and WNBA teams – including Racing Louisville, the Dallas Wings and Indiana Fever – reside in states where abortion is either outright banned or nearly impossible to obtain because of “heartbeat” bills.

Emily Fox, a defender for Racing Louisville and the U.S. women’s national team, said Louisville players have not talked about Dobbs’ impact, but they need to. The club has been an advocate for players’ reproductive choices, and was the first in the NWSL to offer complimentary fertility services, including egg freezing and embryo freezing.

“I do think the club is very supportive of us being able to have a soccer career and do the egg fertility treatments with the partnership,” Fox said. “But yeah, I definitely think we need to have a conversation as a team as it affects all of us.”

While professional athletes might have the resources to travel out of state and obtain an abortion if needed, they worry a state’s hostility toward women’s rights could impact players wanting to move there – or not.

“I had (someone) ask me, ‘Will this impact free agency? Will players not want to go to the Dallas’ and Atlantas of the world?’” said Sue Bird, the 13-time All-Star for the Seattle Storm. “For every woman, that’s a real thing, to think about where you are going to live based on your rights.”

Top players will likely have the cache to publicly oppose trades, but that privilege is reserved for a select few.

“Players have so little leverage when it comes to their careers,” said Becky Sauerbrunn, a defender for the Portland Thorns and co-captain of the national team. “To be able to say where you want to go, for these reasons, I think that’s valid.”

For Sauerbrunn’s teammate, Crystal Dunn, it’s a nonstarter.

“Playing in a red state right now, I would say that’s out of the question,” Dunn said.

Berman, the NWSL commissioner, was noncommittal when asked if the league would block trades players didn’t want because of rights eroding in a particular state. She called the situation “complicated,” and referenced the league’s collective bargaining agreement.

But that doesn’t mean players will be left to fend for themselves.

“Certainly in a situation like that, we would want to have a conversation about how we can ensure that (everyone) feels safe and supported to get the medical care they might need in the place where they’re being asked to live or work,” Berman said. “The league is there as a safety net, to ensure that her medical needs would be addressed appropriately.”

Engelbert said she doesn’t think players want the WNBA blocking trades, and the league will “absolutely” reimburse travel expenses for any employee, including players, who need to go out of state for reproductive healthcare. She also pointed out “the procedures themselves are already covered by the insurance plan we offer to players.”

The U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee made a similar promise. Athletes who get insurance through Team USA can access “family planning benefits” in any state. If an athlete is in a state where some of those services are not available, the USOPC “will cover reasonable travel expenses” for them to go to a state where they are available.

Players are comforted to hear their organizations will help them. But the bottom line, they said, is large portions of America remain dangerous for women.

“I don’t feel like I’m safe because I’m from California or I live in Connecticut,” said DiJonai Carrington, a second-year player with the Connecticut Sun. “The concern remains the same — if we’re not all safe, then none of us are safe.”

Fertility planning and fear for future

It’s not just abortion access that worries athletes.

Besides going after birth control, some states are considering adopting new laws related to in vitro fertilization (IVF) and fertility planning. Some female athletes who have been open about medical procedures, such as freezing their eggs, wonder if family planning procedures will even be legal in the future.

This summer, three-time Olympic champion bobsledder Kaillie Humphries and her husband started the IVF process in Texas. After one round, Humphries wound up with three viable embryos, currently on ice at a Houston clinic.

“Roe wasn’t overturned when I started IVF,” Humphries said. “Now that it is, would I have gone to Texas? No. I have three embryos there – what does this mean for them?”

Athletes also aren’t sure about potential ramifications of traveling to red states while pregnant. Is it safe? What if they had a medical emergency and needed an abortion? In the days after Roe was overturned, multiple stories surfaced of pregnant women in crisis situations who weren’t able to immediately receive medically necessary abortions because doctors feared prosecution.

It is widely accepted that overturning Roe won’t stop abortion, but prevent safe abortion; numerous experts have said the consequences could be deadly for women who can’t get the care they need.

Three months ago, Dunn, a midfielder for the Portland Thorns and member of the U.S. women’s national team, gave birth to a baby boy, Marcel. Pregnancy was tough, she said, even for one of the world’s most in-shape human beings. It was also emotionally taxing. Returning to elite shape took a toll, too – even with the help of a professional trainer, Dunn’s own husband, Pierre Soubrier.

She wouldn’t force any of that on women who didn’t want it.

“If I didn’t want to continue with the pregnancy because my career could be disrupted, that should be my choice,” Dunn said. “I just don’t think if you find yourself pregnant anyone should be able to force you to keep that baby – especially a man.”

Many female athletes worry that in a highly polarized country, with a Supreme Court that skews conservative, rolling back abortion access could be just the beginning – especially with some Republican lawmakers emboldened to revisit other landmark cases, including gay marriage.

“It worries me more not just for myself but for the next generation, what they have to go through,” Wilson said. “They could wake up and lose their rights to anything."

As immediate and urgent as the threat feels – for themselves, their teammates, their families, their friends – there is another, even greater worry. Many women athletes in the United States have always felt a need to leave their games in a better place for the generations coming after them.

It was the driving force in the U.S. women’s long fight for equal pay, and it was a central theme in the landmark collective bargaining agreement reached between WNBA players and the league two years ago.

Now, though, athletes worry the progress made is being hollowed out.

“I don’t want our generation to be the generation that screws it up,” Chicago Sky All-Star Candace Parker said.

She winced when asked whether she’d allow her 13-year-old daughter to play at Tennessee, the school with which Parker is synonymous after leading the Lady Vols to back-to-back NCAA championships in 2007 and 2008.

“I want to be able to say that my daughter has the same rights over her body that my son does,” Parker said. “I don’t know today that I can say that.”

Or, to put it more plaintively:

“I grew up believing girls could do anything, and I’m glad I grew up that way,” Goucher said. “But – it was all just a big lie.”

The team behind the project

Reporting and analysis: Nancy Armour, Lindsay Schnell, Steve Berkowitz, Josh Peter, Chris Bumbaca, Rachel Axon, Emily Olsen

Editing: Alicia DelGallo

Digital design and illustration: Andrea Brunty

Graphics: Jennifer Borresen

Photo editing: Di'Amond Moore

Social media, engagement and promotion: Rachel G. Bowers, Sherlon Christie

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY Sports: Athletes, abortion & anxiety: Pros grapple with eroding women’s rights