Why women are finally making waves in the art market

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

That women are gradually obtaining gender parity in a historically male-dominated art market was emphasised last month at Art Basel, where the fair’s biggest sale at $40 million (£33 million) was a large steel spider by the late Louise Bourgeois.

In the auctions, female artists are increasingly gaining a toehold, arguably even a lead role. A glance through the list of contributors to last week’s £425 million London sales of Modern and Contemporary art shows women as the main barrier breakers in the 20th-century sections.

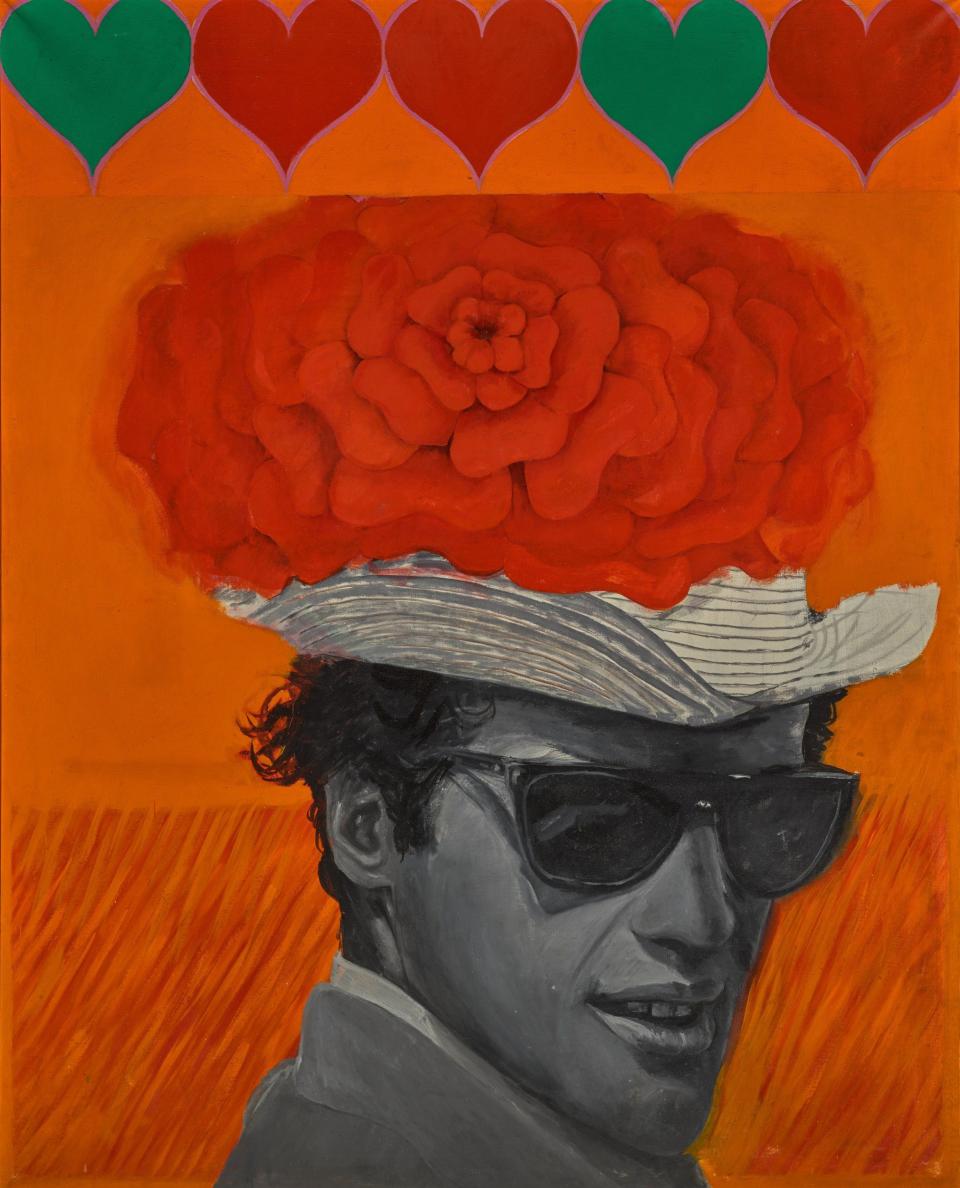

One standout figure was Barbara Hepworth, for whom Bonhams achieved a record £517,000 for a painting, while Christie’s hit a record £5.8 million for a sculpture. Another, signalling the way forward for the younger generation, was the British pop artist Pauline Boty, who died in 1966 at the tragically young age of 28. Her 1962 portrait of French film star Jean-Paul Belmondo soared to a record £1.2 million. The painting had been consigned by a recently divorced French woman, who bought it when the artist was first rediscovered in 1999 for around £4,000.

The biggest leap for women artists, though, is happening in the 21st-century sector. Last May in New York, Sotheby’s staged “The Now” sale, in which the auction house focused solely on the art of this century and packed the first 10 lots with the most in-demand female artists around, setting records for most of them.

A hyper-realist painting, Falling Woman (2020), by Anna Weyant, a new young artist and partner to septuagenarian super-dealer Larry Gagosian, sold for an eight times estimate $1.6 million in only her second auction outing. Queer, mixed-race American Christina Quarles saw her record shoot up from $400,000 in February 2021 to $4.5 million, boosted by her new agent, Hauser & Wirth.

Of the 18 works that exceeded estimates in this sale, 13 were by women. One was the first work at auction by African-American figurative painter Jennifer Packer, who enjoyed a glowingly reviewed exhibition at the Serpentine gallery in 2020. Her 13ft-wide painting, Fire Next Time (2012), doubled estimates to sell for $2.3 million.

Another black female artist hitting record levels last May was Simone Leigh, US representative at this year’s Venice Biennale, but barely seen at auction until 2019. Estimated at $150,000, her terracotta and porcelain head, Birmingham (referring to the 1963 Birmingham Alabama bombing of a Baptist church by white supremacists), attracted at least six bidders before selling for $2.2 million.

It has now become routine for auctions to open their sales with the hottest young artists they can to set the pace. Last week at Christie’s, six of the first seven lots were by women, including the young black British painter Rachel Jones and the aforementioned Leigh and Weyant.

Their contribution may not have counted for as much as the £26 million water-lily painting by Monet that came later, but the energy of bidding multi-estimate sums in the hundreds of thousands left a much deeper impression.

At Sotheby’s Jubilee sale of British art, five of the first six lots were by women – among them a terracotta pot by Magdalene Odundo that sold for a quadruple estimate £302,400, and a Baroque-inspired painting, Boucher’s Flesh, by 32-year-old Flora Yukhnovich, whose works only began appearing at auction last year, that rocketed past a £200,000 estimate to sell for £2.3 million.

Overall, Sotheby’s calculated that 43 per cent of the living artists in their Contemporary Art sales were women. At Phillips, meanwhile, nine of the first 10 lots were by women, led by a recent Slade school of art graduate, 30-year-old Antonia Showering, whose figurative painting We Stray sold for a quadruple estimate record £239,400 in only her second appearance at auction.

Emma Baker, a contemporary art specialist at Sotheby’s, who studied gender issues in 19th-century art at the Courtauld Institute, says the boom is largely to do with supply, “because more women are able to study art than they did in the past”.

“It is also because their subject matter is more in tune with the issues of the day – feminism, race, embodiment,” she adds.

While accepting that collectors and museums may be spending more to diversify their collections, Baker downplays the issue as to whether women have become the next big target for market speculators. “You just have to look at the quality of art they are producing to understand why galleries are showing them and collectors competing for them,” she says. “It’s not just because of their gender.”

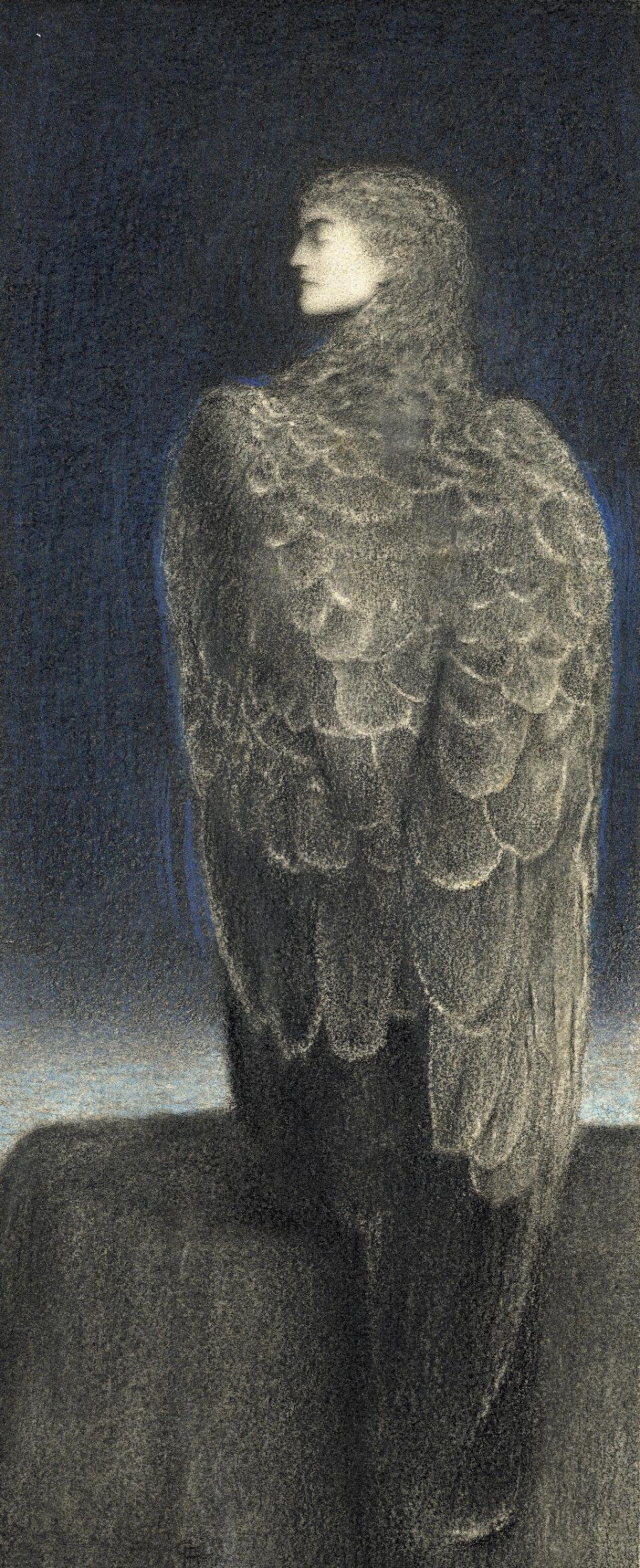

What were wealthy young ladies, with an eye for art, collecting in the 1980s? If Isabel Goldsmith, daughter of James Goldsmith and Bolivian tin heiress Maria Isabel Patiño is anything to go by, it was the ethereal works of the 19th-century symbolists and Pre-Raphaelites. Goldsmith has long been regarded as one of the leading collectors in these fields; she was narrowly outbid in 2010 when Burne-Jones’s watercolour, Love Among the Ruins, sold for a sensational £14.8 million. But now, she is disposing of 87 examples from her collection, valued at over £1 million, by some of the best-known artists, from the Pre-Raphaelite associate Simeon Solomon to the Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff.

Prices, incidentally, have not moved so far since they were bought. One of the top lots, La Médusa endormie, by Khnopff, was bought in 1988 for £130,000 and is now estimated at £200,000. Other works are estimated for as little as £5,000. The collection will be on view at Christie’s from July 9 -14. But in a sign of the times, the sale will not be staged in the flesh, but (less dramatically) by clicks online.

As London embarks on its Old Master sales in the auction rooms, dealers are taking to the floor to show off their knowledge and the discoveries they have made for London Art Week. Miles Wynn Cato, for instance, recounts the constant searching, reading, dreaming and sharp intakes of breath that go into his discoveries as he unveils 14 recent examples by the likes of Thomas Gainsborough and Thomas Lawrence, each one a worthy subject for the BBC’s Fake or Fortune programme.

So, also, is a portrait of a roughly clad elderly man at the Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker gallery that had been attributed by Christie’s to William Tate, a student of the 18th-century master of light and shade Joseph Wright of Derby, when they sold it in 2008 to a private collector for a modest £3,250.

Then, in 2020, Libson and Yarker acquired it from the collector and have now established it as by Wright himself, by relating it to a similar work in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery entitled The Hermit. “The crisp fabric, brick walls, concealed light source and the way the flesh is built up all pointed to Wright’s hand at work,” says Yarker. The painting, to be published in a forthcoming catalogue raisonné, now has an asking price in the region of £400,000.