Why Troost? What’s the history of KC BBQ? What happened to the Plaza bells? KCQ helps find the answers

You ask good questions, Kansas City.

Over the past year, Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library staff members have dug into a country club owner with Mafia connections, climate change across the metro area, a famous World War II-era poet, glass recycling and so much more.

The inspiration for these stories came from curious community members who submitted their questions about Kansas City — past, present and future — to “What’s Your KCQ?,” a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library.

Readers asked about the history behind Troost Avenue’s name, if a picturesque beach in a vintage post card was really located in the metro area, and about how Kansas City-style barbecue developed — and that’s just to name a few.

Now we’re looking back at what we’ve learned about Kansas City this year thanks to those questions — and asking for your help finding the answer to an unsolved KC mystery.

Troost Avenue named after slaveholder

Troost Avenue has become known as Kansas City’s dividing line — and its roots run deep in the city’s history of racial segregation and slavery.

A reader asked ”What’s your KCQ?” about its origins: “Wasn’t Troost Avenue named after a slaveholder who had a plantation at 31st and Troost?”

We dove into records kept by the library, through decades of newspaper clippings and, of course, a thorough Google search to learn more about who Troost Avenue is named for and what used to be along the road.

The answer? Yes and no. Its namesake, one of Kansas City’s founding fathers, was a Dutch physician and slave owner. The slave plantation was owned by a preacher.

Born in Holland in 1776, Dr. Benoist Troost moved to Kansas City around 1847 after serving as a hospital steward in the Army of Napoleon. He was the city’s first resident physician. Troost was one of the trustees when the town of Kansas was incorporated by the county in 1850, according to documentation provided by the library, and again when the Missouri General Assembly incorporated the city in 1853.

Troost also built the area’s first brick hotel, helped publish and finance an early newspaper and ran for mayor, losing to William S. Gregory.

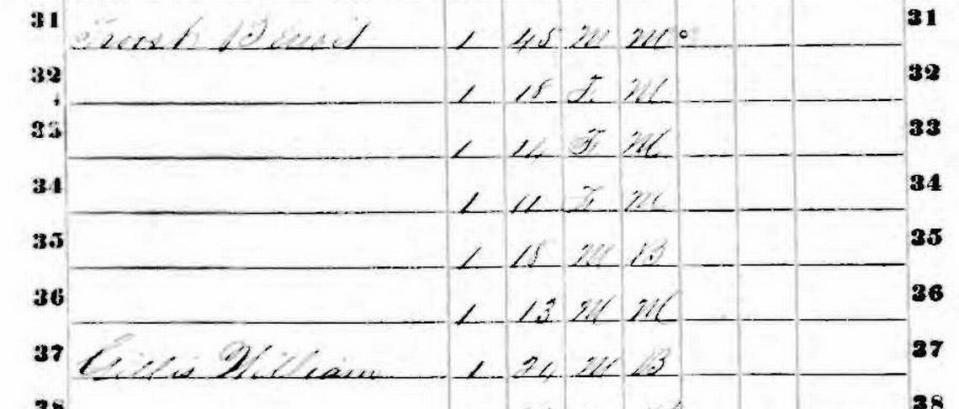

An 1850 Federal Census Slave Schedule record, provided by the public library, shows Benoist Troost owned six enslaved men and women in 1850.

He did not, as far as The Star could find, own a plantation at 31st Street and Troost. He was known to have an estate southeast of the city.

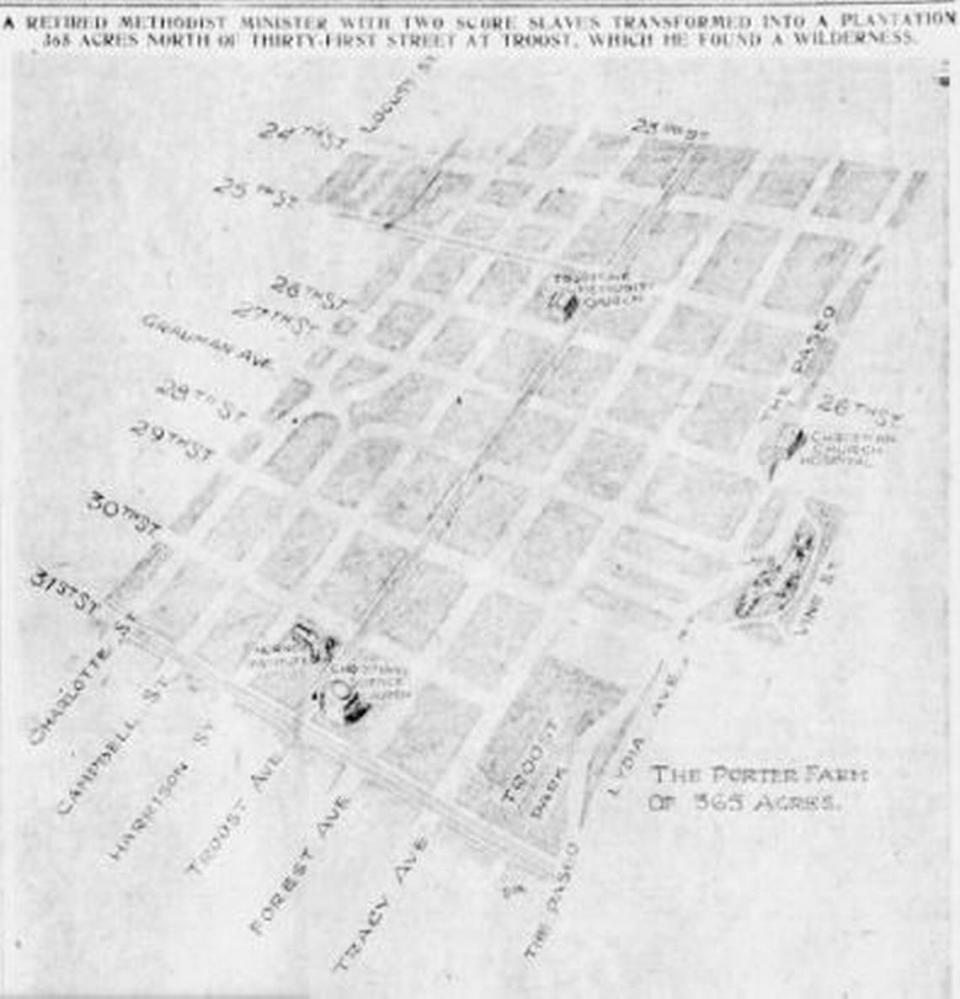

However, the Rev. James Porter did own a plantation there. Porter was Kansas City’s first Methodist preacher. His family established the Porter Plantation, where they enslaved between 40 to 100 people, in 1834. It was bordered by 23rd and 31st streets on the north and south and from Locust Avenue to Vine Street, taking up about 365 acres.

After the Civil War, they began selling off some of the lots, which led to the creation of “Millionaire’s Row.”

In the late 19th century, Troost Avenue became the place wealthy families sought to live, and the community flourished.

Then came redlining.

In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration basically codified residential segregation when it refused to insure mortgages in and around Black neighborhoods and subsidized the creation of white-only subdivisions.

That practice and the development of racially restrictive covenants led to two housing markets divided by race. Housing advertising in The Star carefully specified properties as east or west of Troost Avenue, now the boundary of racial separation in Kansas City.

Reported by The Star’s Cortlynn Stark

‘Atlantic City of the West’

Finding a beach during the dog days of summer can be a challenge for landlocked Kansas Citians. Though the area has plenty of smaller beaches, the quest often includes long-distance travel and can decimate vacation budgets.

Reader Tyler Smith came across some old photos of locals while away on long summer days at a picturesque beach a mere 20-minute train ride from downtown. He asked “What’s Your KCQ?” to help explain where the beach was located and what exactly happened to it.

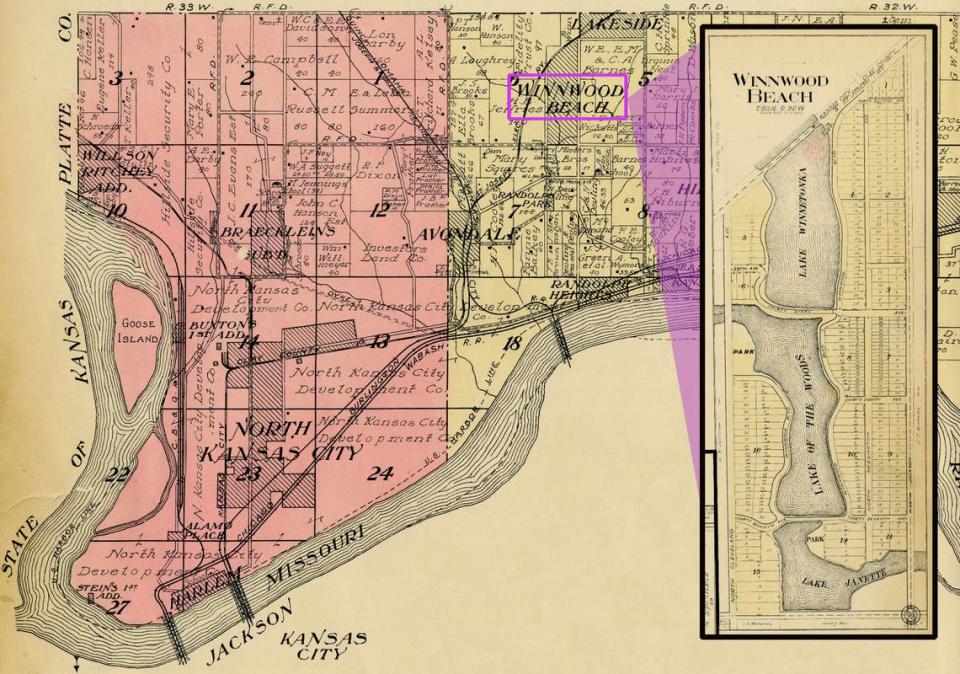

The place was Winnwood, a Clay County resort that encompassed multiple lakes and featured a variety of amusement attractions and 300 building lots on the water. The park took its name from its founder, Frank Winn.

Winn’s family arrived in the county in 1850. He was educated at William Jewell College in Liberty and, with his father, became a successful hog farmer. Winn became known for his prize-winning Poland China hogs and seemingly could have been a success focusing solely on livestock, but the young entrepreneur had real estate on the brain.

He began planning a lake on the family property abutting the planned Kansas City, Clay County and St. Joseph Electric Railway line. The Armour-Swift-Burlington (ASB) Bridge, connecting downtown Kansas City with Clay County to the north, was completed in 1911, and interurban trains began running to St. Joseph and back in 1913. Winn dammed a creek on the property, and the clear, spring-fed waters of Winnwood Lake were born.

The initial plan was only to subdivide the land and sell lots to those seeking a rustic home or vacation cottage with easy access to hunting and fishing, but a 1911 trip to Atlantic City changed Winn’s mind.

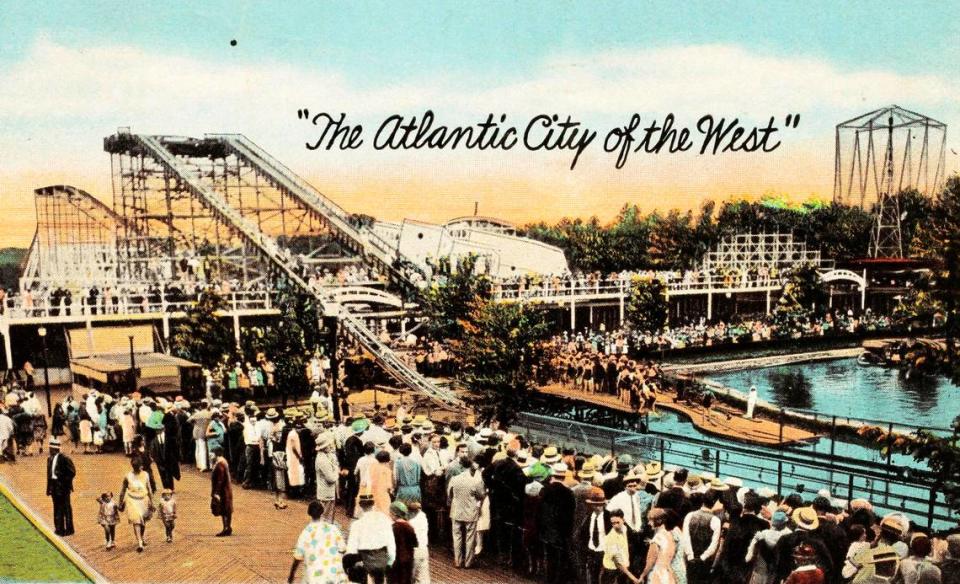

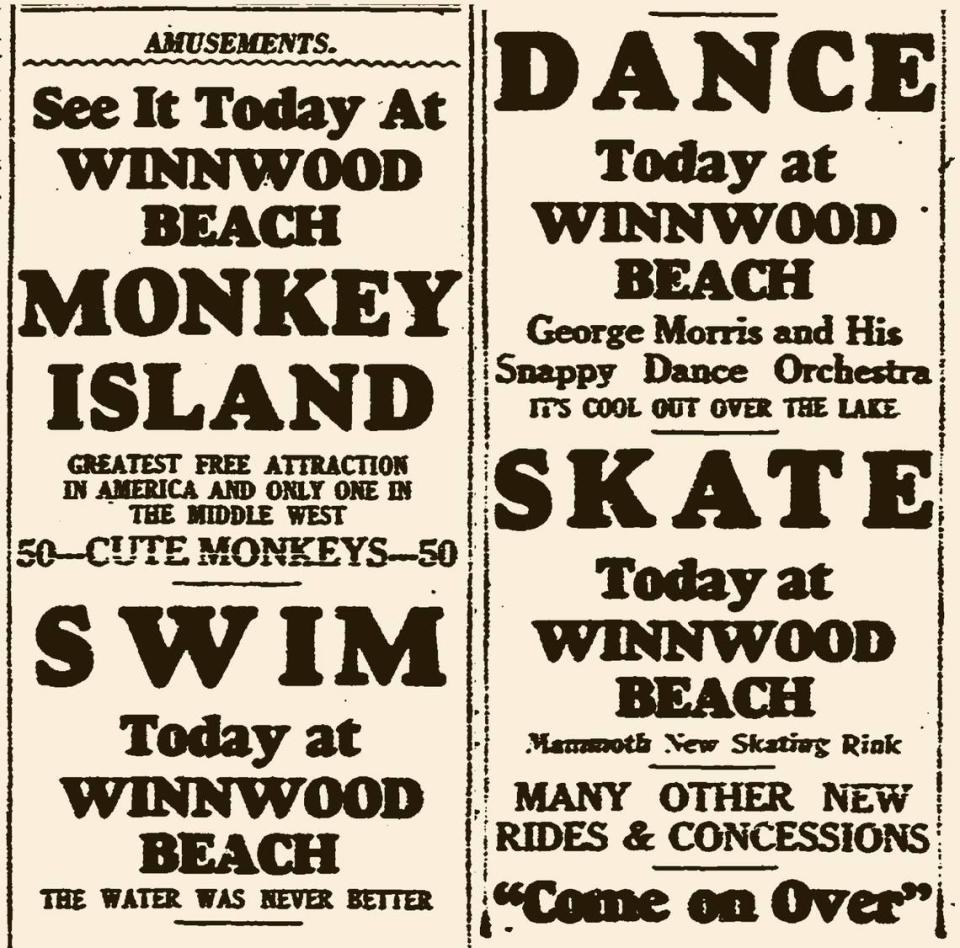

Back in Clay County, he created an 800-foot sandy beach along his lake’s shore. By 1913, the dance pavilion and a canoe rental house were added. Over the years, Winn added a three-story bathhouse, a diving platform, water slides, amusement park rides (including two roller coasters), a zoo, a roller skating rink and even a “monkey island.”

The feather in Winn’s cap, however, was a 40-foot-wide boardwalk built to mimic the one he had seen on his trip east. Winnwood Beach took on the nickname “The Atlantic City of the West.”

Once the roads were improved, buses and automobiles brought even more people to the park. At the height of its popularity in the 1920s, Winnwood Beach occupied 150 acres and saw upward of 10,000 visitors on busy Sundays. The cottages springing up around the resort sold well.

However, Winnwood Beach’s heyday wasn’t destined to last. A series of unfortunate events, including a fire, a boardwalk collapse and a dam burst, coupled with the toll the Great Depression took on admissions, eventually caused the beach to go out of business.

Reported by KCPL’s Michael Wells

The history — and tragedy — behind the name ‘Black Bob’

Olathe, the county seat of Johnson County, is covered with the name Black Bob: Black Bob Road, Black Bob Elementary School, Black Bob Park, Black Bob Bay water park, Blackbob Marketplace, Black Bob Court Townhomes, Blackbob Pet Hospital, Blackbob Park Batting Cages & Mini Golf.

Olathe is, without question, the Black Bob capital of the world.

“When I first heard of it, I thought it was one word ‘blackbob’ and the name of some kind of plant or something,” Tim Danneberg, Olathe’s director of communication and customer services, wrote in an email. “But when I saw the actual sign, it made me wonder, who was Black Bob, why is the road named that, and in these times, SHOULD it be named that?”

The simple answer is yes — unless you also consider honoring Native American chiefs such as Tecumseh, Sitting Bull and Geronimo to be offensive.

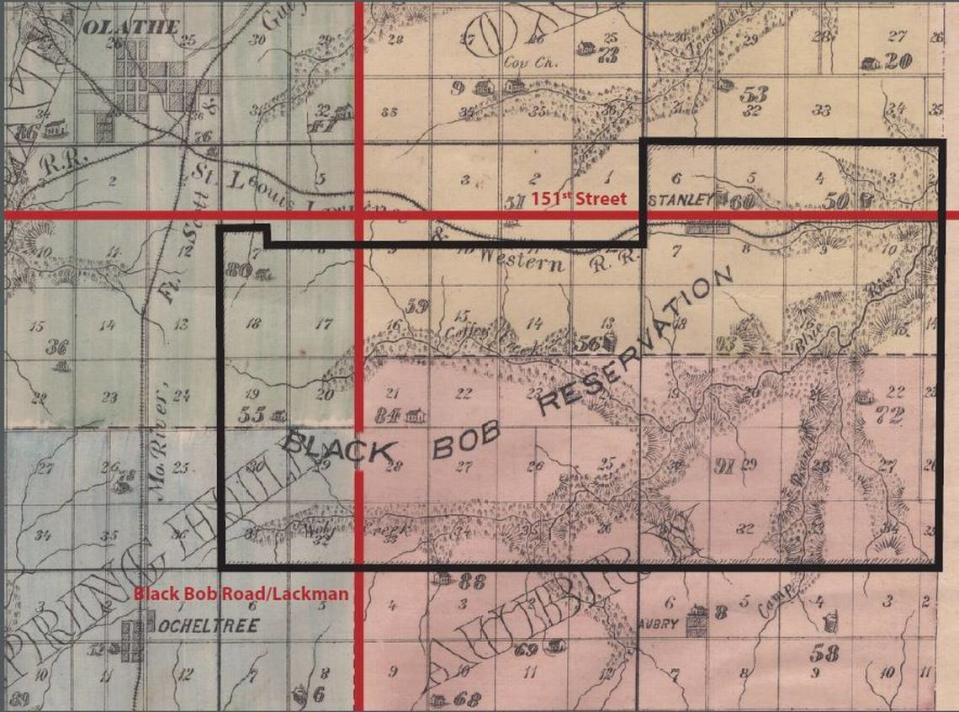

Black Bob, a Native American who was half Miami and half Shawnee, led a band of Shawnee inhabiting the Olathe area in the 19th century. The band, as well as a reservation that filled much of Johnson County, came to be named after Black Bob, so a street in his honor seems entirely logical.

“This issue arises from time to time that perhaps the name Black Bob Road has a racist connotation,” said Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee tribe. “That’s absolutely not the case.

“To actually name it after an individual, I don’t see a problem with that whatsoever.”

And, no, his name didn’t come from his skin color, but rather from his bobbed black hair.

Of course, none of this sugarcoats some elements of shame to the Black Bob story. As was the case with most Native Americans, mistreatment by white people was common. And with the Black Bob Band, it rose to the highest level of government.

When the federal government removed the Shawnee from Missouri to eastern Kansas in 1825 under the Treaty of St. Louis, Black Bob and his Cape Girardeau Shawnee band refused to go, claiming they had been misled by the government, and settled instead in northern Arkansas.

Members of what came to be called the Black Bob Band even petitioned directly to President Andrew Jackson. They said they had lived “peaceably” in “Upper Louisiana” for 40 years and that the Shawnee lands in Kansas had “a climate colder than we have been accustomed to, or wish to live in.”

That got them nowhere.

Eventually they relocated after an 1854 treaty gave them rights to 33,000 acres in what is now southeastern Johnson County, establishing the Black Bob Reservation. The Black Bob remained independent from the rest of Kansas’ Shawnee nation, however, and defied the Shawnee national council that was largely allied with the federal government.

Unlike most tribal organizations, the fewer than 200 members of the Black Bob believed in holding their lands in common rather than individual tracts. But the 1854 treaty had assigned the land in 200-acre allotments.

During the Civil War, the Black Bob were harassed and attacked by both Missouri bushwhackers and Kansas thieves, and they fled to Oklahoma Indian Territory. When they returned to their Kansas lands after the war, they found squatters inhabiting them and government agents illegally selling tracts.

That led to a nasty decades-long legal battle involving the Black Bob, the federal government and Johnson County officials. Some tribe members were tricked into selling rights to their land for almost nothing. The Star wrote, “One thirsty brave signed his over for a jug of whisky. Some got nothing at all.” Speculators would resell the land for $8-$12 an acre.

In 1870, a petition from “citizens of Johnson County, Kansas” to Congress suggested they deserved the Black Bob lands, claiming “the Indians are deriving no benefit from the sale of their lands, but squander the money they receive in drunken frolics, and are led to commit murder and other heinous crimes, and reduce themselves to vagabondage and ruin.”

The frenzy over land claims and titles among settlers led to the killings of at least two white men.

In 1895, a government special master issued a final settlement in the dispute that ordered settlers to pay $5-$10 an acre for land determined to be worth an average of $20 an acre.

Reported by The Star’s Dan Kelly

The barbecue capital of the world

When you think of Kansas City, you think of a – perhaps the – barbecue capital of the world. But how did we get here?

One thing that all regional styles have in common is the contribution of foodways pioneered by and passed down to the descendants of Black Southerners. The Great Migration, the massive population shift of African Americans out of the South and into northern and Midwestern cities in the early 20th century, helped accelerate this culinary evolution. These new arrivals came seeking work and business opportunities, hoped for a better life for their children, and in the process, gifted us with our signature style of barbecue.

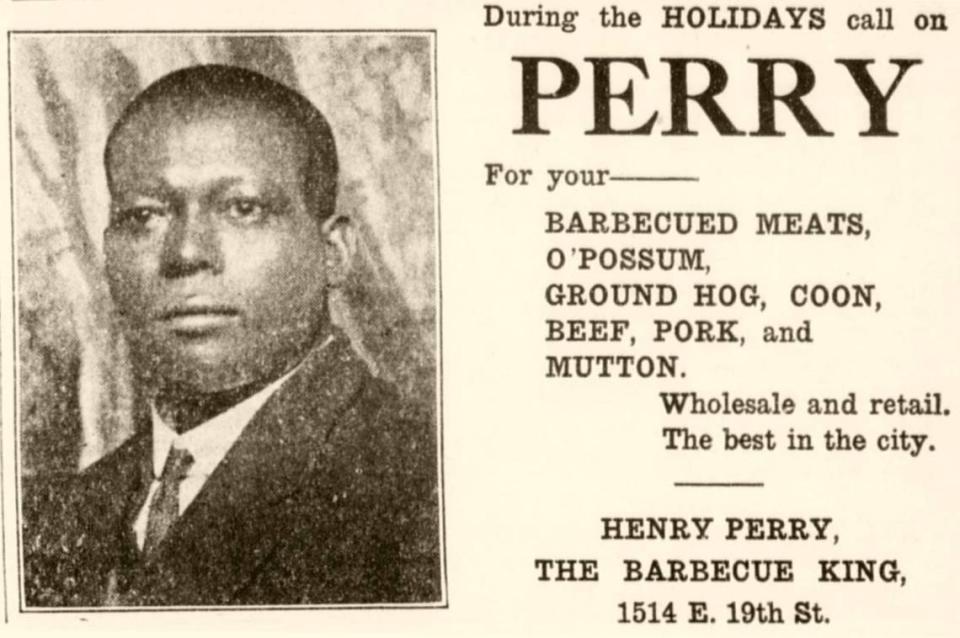

The relationship between the Great Migration and the development of Kansas City barbecue is perfectly encapsulated in the story of King Henry Perry.

Born in Tennessee in 1875, Perry worked as a cook aboard Mississippi River steamships, where he began to develop his craft. In keeping with the Memphis barbecue style, those who tasted his sauce described it as thin, vinegar-based and so heavy on the cayenne pepper that his customers often winced. He rambled about the Midwest, spending time in Chicago and Minneapolis before arriving in Kansas City in 1907. First working as a porter in a Quality Hill saloon, it wasn’t long before Perry had taken to selling barbecue from a stand in the city’s Garment District.

By 1911, Perry had relocated to a tent at 18th and Vine streets, where he tended a brick-lined pit dug into the ground and already called himself the Barbecue King. Speaking with a Kansas City Star reporter, he described having a hard time making barbecue pay the bills. He admitted, “Lots of times I just throw up my hands and quit altogether and get me a job at $8 or $10 a week.” But, he continued, “I can’t stay away from it. Every time I drift back to this little old tent and start a fire under some kind of a piece of meat.”

Perry pitched his tent where his barbecue would sell. In time, he gave up finding other jobs, settling into brick-and-mortar locations, first at 19th and Vine and later at 19th and Highland. By the time of the 1930 census, Perry reported the following: “Occupation – Barbecue; Industry – Barbecue.” The King had claimed his realm.

Despite staying close to the heart of Kansas City’s vibrant Black community, he developed a following that crossed racial barriers. In 1932, a reporter for The Kansas City Call wrote, “With a trade about equally divided between white and black, Mr. Perry serves both high and low. Swanky limousines, gleaming with nickel and glossy black, rub shoulders at the curb outside the Perry stand with pre-historic Model T Fords.”

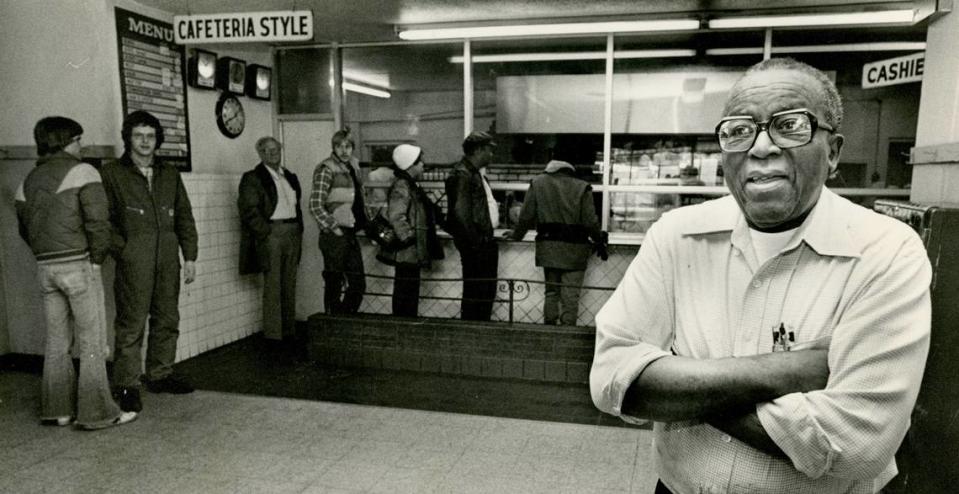

Through Pinkard, the Perry tradition was passed on to the Gates family, and Ol’ Kentuck eventually became Gates Bar-B-Q. Pinkard retired not long after the Gateses took over the business, relocated to St. Louis and died there in 1963. Today, a photograph of Pinkard can be found in all Gates locations.

When Perry died in 1940, he left his business to his protégé, Charlie Bryant. The rebranded Charlie Bryant Barbecue was moved to a larger space at 18th and Euclid. Charlie ran the business until retiring in 1946.

Then the business was handed over to his brother and fellow Perry protégé, Arthur.

One of Arthur Bryant’s biggest transformations to the business was his sweeter, tomato-based barbecue sauce, a change from Perry’s and Charlie Bryant’s thin, vinegar-based and spicy sauce.

The sauce served up at the renamed Arthur Bryant’s Barbecue became legendary and transformed Kansas City barbecue into what we know it as today.

Reported by KCPL’s Michael Wells

An unsolved mystery

We need your help with this one.

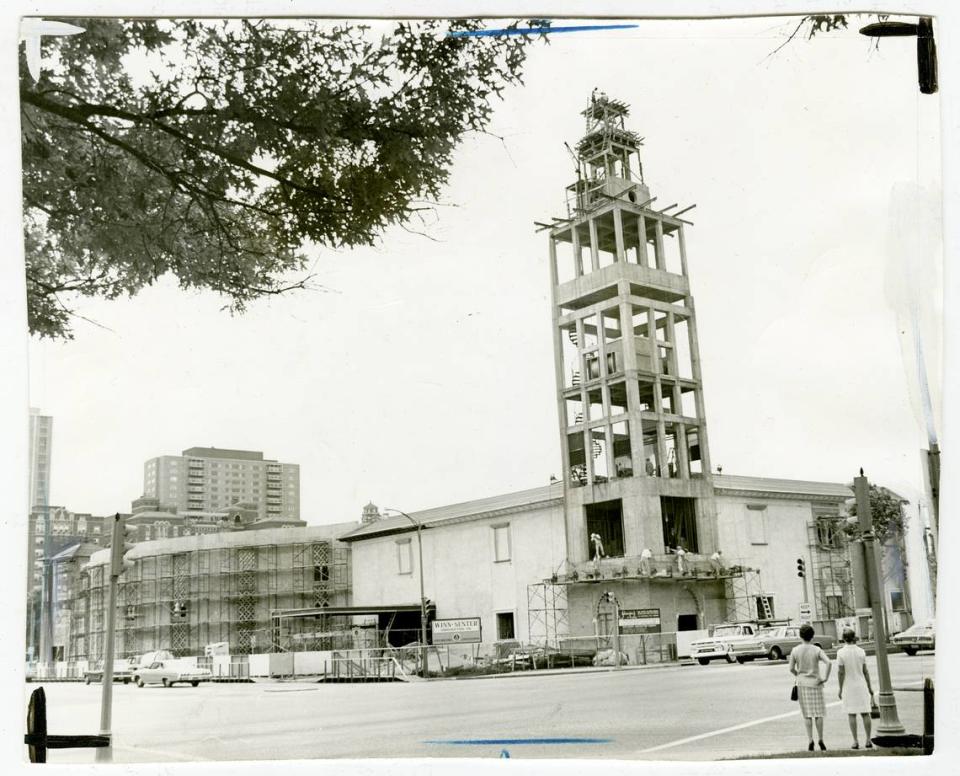

When construction ended in 1967, the Giralda Tower became the tallest structure on the Country Club Plaza. A smaller version of the more than 800-year-old Giralda tower in Seville, Spain, it included a carillon of 600 bells that could be operated manually or by an automatic roll player. Originally, the bells were set to chime on the hour and music was played daily.

Judith Cappaus recalls hearing the carillon — which is a set of bells, usually hung in towers — play “America the Beautiful” in the mornings after she moved to the Plaza area in 2003. But she has not heard the bells in several years and wondered what happened to them. She turned to “What’s Your KCQ?”

While the construction and architecture of the Giralda Tower are well documented, the status of the carillon is not. Newspaper, database and internet searches yielded no recent information. We also reached out to the owner of the Country Club Plaza, Taubman Realty, which acquired the property in 2016. Its current management team also had no details.

The 138-foot Giralda Tower and accompanying 38-foot Seville Light Fountain at West 47th Street and Mill Creek Parkway were dedicated on Oct. 12, 1967. Construction of the tower had been in the works for decades. Plaza developer J.C. Nichols had wanted to build a replica of the Giralda tower as early as 1929 but could not find the right location for it. When the Chandler Landscaping and Floral Company left the corner just southwest of the former J.C. Nichols Memorial Fountain, his son, Miller Nichols, decided it would be the perfect site.

Kansas City’s tower is approximately half the size of its Spanish counterpart. Its adjoining retail building originally housed Swanson’s, a high-end department store. Today, that space is home to the Cheesecake Factory and Forever 21.

Details about the carillon inside are difficult to find, though not impossible. Over the years, The Star printed a few brief articles about it.

After 1981, the trail mostly runs cold. The tower’s bells are occasionally referenced in Plaza promotional materials in the 1990s and into the 2000s, but only that they chimed to mark the hour or half-hour and that concerts occasionally took place.

This is where we could use your help. When is the last time you remember hearing the Giralda Tower bells? Do you know someone who played them or performed maintenance on them? Have you ever been inside the tower itself? Email us at kcq@kcstar.com.

Reported by KCPL’s Kate Hill

Have a question of your own? Email kcq@kcstar.com or visit kclibrary.org/kcq.