Why this Miami-based architect just had ‘the best year an artist could have’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Germane Barnes was a young architect and recent graduate when he was faced with two choices. Move to Paris to work at a renowned architectural firm or design community spaces for a South Florida city he had never heard of, Opa-Locka.

To his parents, the choice seemed obvious. They didn’t put him through 13 years of French classes for nothing, Barnes said. But much to their confusion, he took the job in Opa-Locka. He chose wisely.

That was in 2013. Ten years later, Barnes has become a rising star in both architecture and the arts, earning a laundry list of accolades, awards and grants while working as an assistant professor at the University of Miami. His work — which explores the links between architecture, race and identity — has been featured in international publications and venues. He founded Studio Barnes in 2016, won the prestigious Rome Prize in 2021, showed his artwork at a groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and recently joined Miami-based nonprofit Oolite Arts’ board of trustees.

On Saturday, he added another trophy to his crowded shelf. He accepted the Arison Award at the YoungArts Miami Gala, an event hosted by the nonprofit which supports young artists. Barnes, who works with YoungArts teaching master classes, said this award was especially meaningful.

“The ultimate way to give back is to help young people, and that’s what YoungArts allows me the opportunity to do,” he told the Herald.

Sarah Arison, the chair of the YoungArts board of trustees, described Barnes as “one of the most compelling and relevant architects working today.”

“The Arison Award is given annually to individuals who embrace this same mission and are committed to helping young artists and our arts ecosystem grow and thrive,” Arison said in a statement. “In addition to being an extraordinarily talented and accomplished architect, Germane is constantly thinking of others and how he can most help communities in need.”

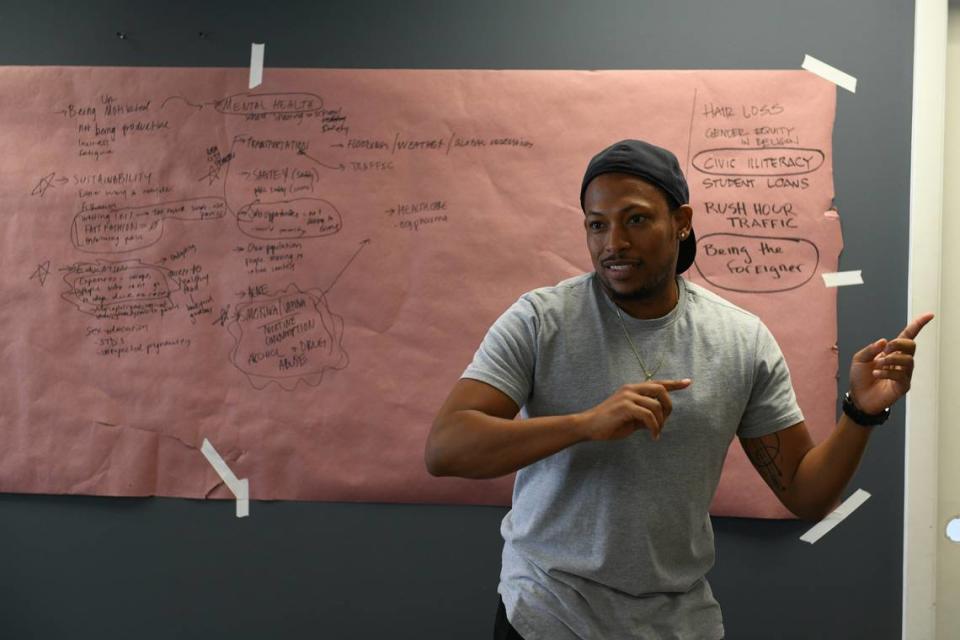

Barnes’ artistic work is driven by thinking of others. His designs don’t just focus on the buildings themselves but rather the people who use them. That means involving community members throughout the process of designing a space, even if that means more time and effort, he said.

In his hometown of Chicago, he designed “Block Party,” a bounce house-like structure inspired by the city’s block parties for the Chicago Architecture Biennial. At Brickell City Centre, he made an installation based on porch stoops in African-American communities. And in Delray Beach, Studio Barnes is working with nonprofit Thrive Collective to turn an old UPS truck into a mobile museum and designing a straw market in homage to the local Bahamian community.

“A building’s a building, but it doesn’t become anything special until people are in it,” Barnes said.

‘No, stupid.’

Barnes grew up on the west side of Chicago. By age 5, he knew he wanted to become an architect, though he’s not sure why, he said. He didn’t know any architects growing up.

Maybe it was the beautiful homes in Oak Park, a wealthy town where Ernest Hemingway and Frank Lloyd Wright used to live that was right next to Barnes’ neighborhood on the edge of Chicago. His mother would tell him, “If you want to design those, you’d have to be an architect.”

But he had to start somewhere. At 14, he spent a summer working at his first job: painting a mural for the local library.

He went on to study architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, but for a moment, he said he felt confused. He didn’t know the possibilities of architecture besides building houses and skyscrapers.

“At the time, there wasn’t an emphasis on socially engaged architecture or grassroots, community-oriented architecture,” Barnes said. “It was more so just, ‘Here’s how you put a building together and make sure it gets stamped so you don’t get sued.’”

An internship in Cape Town, South Africa, showed him that there was more to architecture than just building high rises. In 2008, Barnes went to work under Sean J Mackay Architects, making a bunch of extremely expensive, high-end residential homes.

“I was like, ‘Alright, so this is what I’m going to be doing for the rest of my life?” Barnes recalled.

“No, stupid,” his boss said. “This just pays the bills.”

When they weren’t building luxury buildings in Cape Town, they were out in the low-income townships outside of the city doing pro bono design projects. That experience taught Barnes how architecture can engage communities and help marginalized people.

“Literally everything changed in that moment,” he said.

Everything would change again after Barnes finished grad school. He went to Paris to work with the late French architect Francois Perrin who put him on projects with Xavier Veilhan, a prominent artist.

He was immersed in installations, not buildings. Architecture is slow and tedious. Installation is fast and freeing, Barnes said. He realized that he could do both.

Veilhan later offered to get Barnes another job in Paris at renowned architect Jean Nouvel’s office. Of course, Barnes said yes. He didn’t take 13 years of French classes for nothing.

But, Barnes and two other designers had applied for a public art proposal competition with Miami-Dade County and the National Endowment for the Arts. The client was the Opa-Locka Community Development Corporation. They won.

His parents wondered why he would pass up Paris for “some weird place called Opa-Locka in South Florida.” In Paris, Barnes said, he would be stuck in the office basement making models all day. But in Opa-Locka, he was the leader of the proposal. He could make a real impact faster.

And he did. The group designed a park, turned an old roofing company into an arts and recreation center and made an urban farm where an empty patch of grass used to be. Barnes’ designs helped revitalize the area without gentrification. He’s lived in Miami ever since.

‘The best year an artist could have’

The recent whirlwind of attention was not part of Barnes’ plans.

“I would be lying to you if I said I knew I would get all this. Absolutely not,” he said. “I was perfectly fine just doing the work and nobody knowing who I was. To me, it’s about the people.”

“Then all of a sudden,” he added. “Everything just flipped overnight.”

In early 2021, Barnes’ artwork was featured in “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America,” an exhibition at MoMA in New York City that explored the relationship between architecture and Black communities. It was the first time the museum showed Black architects.

Sean Anderson, a Cornell University associate professor who used to work at MoMA, curated the show with architect and Columbia University professor Mabel O. Wilson. As they planned the show, Barnes was one of the first artists they wanted to include, Anderson said.

“It’s incredibly unique and unusual to find an architect and artist working at the scale and level that he is with such sensitivity,” Anderson said. “But also he’s having fun. That’s huge.”

Barnes, the youngest architect in the exhibition, made a floating spice rack and series of collages inspired by Miami’s diverse Black and immigrant communities. The piece, called “A Spectrum of Blackness,” took off in the press. It resonated with audiences who are oftentimes “intellectually priced out” of museums, Barnes said.

“It was very personal, and it was across ethnicities,” Barnes said. People from Panama, the Dominican Republic and Chicago were all able to recognize the same ingredients and feel represented.

Since the MoMA show, Barnes’ notoriety only grew. Dennis Scholl, the Oolite Arts president, commended Barnes’ ability to continue to produce high quality work despite the high demands and obligations.

Last year, Barnes debuted “Rosie’s Fare,” an installation at Oolite Arts in Miami Beach that was inspired by his grandmother Rosie and the underappreciated labor of African American women. He recreated a kitchen and included elements from his MoMA installation, like the spice rack.

“Germane Barnes has had one of the greatest years any Miami artists has ever had for all time,” Scholl said. “When you think about the various awards and prizes that he has received, its just been an extraordinary run for him, of course, with the Rome Prize being the pinnacle of what you can achieve as an artist.”

This past winter, as thousands of art lovers flocked to Miami for Art Basel, Barnes paid homage to Miami’s diverse communities and Carnival with “Rock | Roll,” an interactive installation in the Design District. Barnes designed colorful domed rocking chairs decorated with pool noodles to mimic feathered Carnival regalia.

“He’s an emerging personality to watch,” said Craig Robins, the Design Miami co-founder and Design District developer. “He’s clearly got his finger on the pulse and has his own perspective, so he’s one of the people that has the potential to influence future generations.”

Sharing the joy

In the United States, just about 2 percent of licensed architects are Black, according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards.

In the six and a half years Barnes studied architecture, he never had a Black professor or teaching assistant. At the University of Miami, Barnes said he mentors students of color who otherwise may struggle to find someone they can relate to.

“In my mind, it’s a way of giving that to students who may share the same story as me or the same upbringing as me,” he said. He advises students to never offer their labor for free and to think about the different paths they can take with architecture, even without a license. (The guy who designed Nike Air Jordans was an architect, Barnes said.)

For the last five years, Barnes has spoken with the up-and-coming artists who come through YoungArts’ program. The nonprofit is critical to nurturing the next generation of creatives, Barnes said. He wishes he knew about it when he was a teenager.

Despite the number of grants and prizes he’s received before, Barnes said the Arison Award was special, not just because of his ties to YoungArts but also because of who was there to see him accept it.

Barnes’ mother, who worked at the energy company Con Edison throughout his childhood, never got to see her son accept an award before. That finally changed on Saturday.

“There’s a lot of sentimental value in the fact that this organization has been so kind to me,” Barnes said. “My mother will be able to share in the joy of me receiving this amazing award.”

This story was produced with financial support from The Pérez Family Foundation, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.