'We're still open': Restaurants across America in the time of coronavirus

There’s nothing quite like dining out. Enjoying a large meal with family, sharing an intimate candlelit table with a date, splitting appetizers and drinks with friends … we’ve lost all of that over the past two months, and the restaurants that once served us have lost even more.

There’s no uniform national policy for reopening restaurants; different areas have suffered different rates of infection, and competing political, economic and public health priorities have resulted in some restaurants opening, while others stay shuttered.

Over Memorial Day Weekend, we checked out the restaurant scene in three of America’s largest cities. Here’s what you can look forward to in your town, now or later this summer.

ATLANTA

With the declaration that he doesn’t “give a damn about politics right now,” Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp on April 20 authorized the reopening of the state’s restaurants a week later. The move drew nationwide heat, and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms responded by telling Atlantans to “please stay at home.”

Confusing directives, to be sure, and one of the resulting victims has been Atlanta’s restaurant scene. A wave of new infections hasn’t shown up in Georgia, but neither have diners.

Per state order, restaurants open to the public are enforcing social distancing, sometimes with polite taped signs, sometimes by just yanking entire tables out of the joint. The weather is getting nicer in Georgia, so along with active takeout lines, many restaurants across the state are placing tables out in the open air. It’s a pleasant time of year in Atlanta, and were it not for the fact that the servers are wearing masks, you could almost forget it was 2020.

Atlanta has always been a fiercely competitive culinary town, a tight-knit combination of see-and-be-seen steakhouses, line-out-the-door indie diners, and comfortable, low-risk chains. Pick a school of cooking and there’s somebody doing it well in Atlanta … or there was, at least, until mid-March.

Now the list of memorable restaurants that have closed and may never reopen is vast and growing. Others have tried to pivot away from sitdown service. Sign after sign posted in front of Atlanta’s restaurants virtually begs passersby that WE’RE STILL OPEN, TAKEOUT AVAILABLE.

It will take years for the city’s dynamic restaurant scene to recover, regardless of when reopening happened. The possibility of infection is keeping people off the streets, and restaurants are feeling the pinch.

“Every business, even government offices, where people are able to go in and out, [the possibility of infection] has crossed everyone’s mind,” says Njeri Boss, director of PR for Waffle House, one of the first restaurants to reopen. “It’s a difficult balance to walk. We are doing everything the federal government, the CDC, and the state [of Georgia] health department are recommending to be safe.”

COVID-19 has hobbled Atlanta’s food halls, collections of high-end restaurants where you can sample an array of world cultures without leaving one city block. But food halls are built on community, with long tables and shared seating, and nobody is much in the mood for getting to know strangers right now.

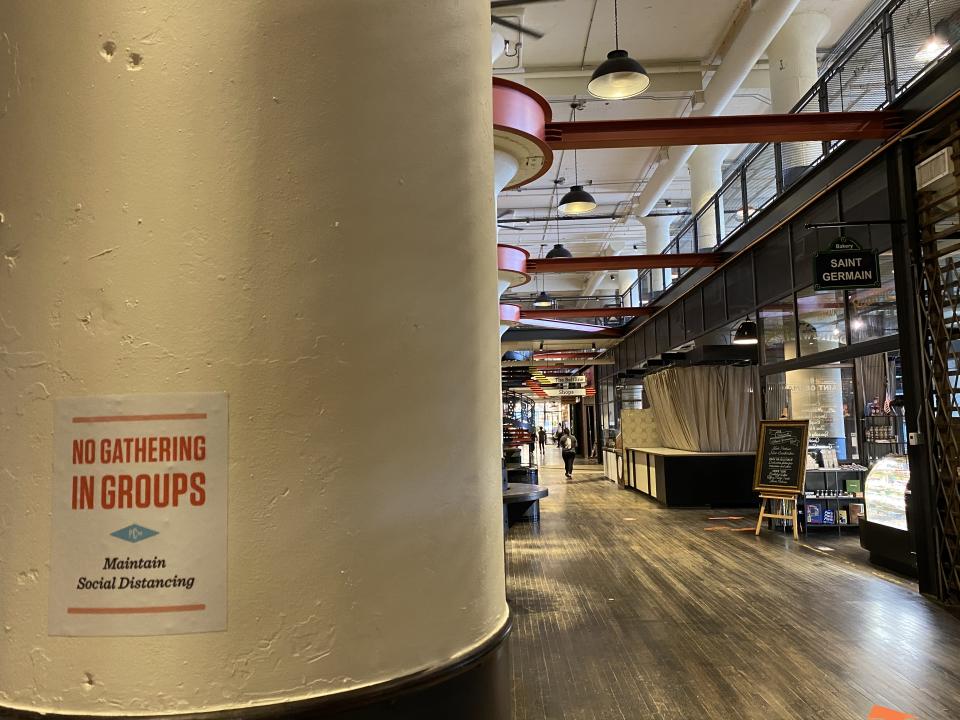

Many are takeout-only, a get-your-food-and-get-out operation that defeats the entire ethos of the food hall. Others, like Ponce City Market, a marvel of downtown renovation that reopened only a few days ago, are running at maybe 20 percent of efficiency. Many restaurants remain shuttered, some with “CLOSED UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE” signs dated March 17, 2020.

A few blocks north, the usually thriving Virginia-Highlands district is as deserted as a beach boardwalk in wintertime. The original location of Taco Mac, one of the city’s classic sports bars, is all but empty, one server handling the three tables with customers. Just because the doors are open doesn’t mean anyone’s ready to walk back in just yet.

North of town, in the Avalon development so brutally skewered by the Washington Post a couple weeks back, there’s more activity. The observations of one reporter are in no way comprehensive or authoritative, but this reporter observed at least two dozen mask-free people walking right past signs that read, “For the safety of our community and guests, please wear a mask while visiting Avalon.”

When you’re one of the few diners in a restaurant, you’re the focus of attention. Some people revel in that; diners sitting at tables just outside Rumi’s Kitchen on the sidewalks of Avalon look outward on the world passing by as if daring the virus to come ask to join their party. Others, like a trio in Jia, a Szechuan restaurant in Ponce City Market, huddle close together in the shadow of stacks of chairs. Still others, like the family in an Italian chain restaurant, speak in voices far louder than necessary for the empty room around them.

The vibe in restaurant after restaurant is that of nervous anticipation, that feeling you get when you’ve swam out just a little past your comfort zone.

Nobody seems very happy. Nobody seems truly at ease, not yet.

— Jay Busbee

CHICAGO

On bright, breezy Friday evenings in late-May, in anything resembling Normal Times, Chicago hums like few American cities can. Lively music and voices waft out onto bustling downtown streets. Wine glasses and silverware clink. A melting pot of scents fills sidewalks. Privileged North Side neighborhoods jump with excitement and verve.

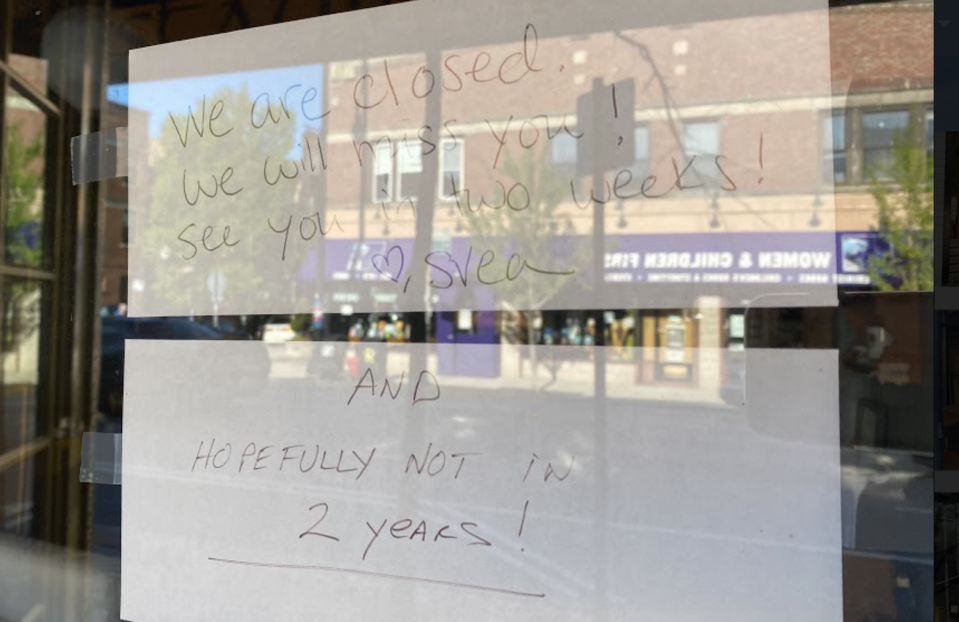

But on this Friday evening, of Memorial Day weekend 2020, there is virtual silence. The occasional car swooshes by and breaks it. Pedestrians rarely do. On patios that once popped, tables and chairs have been dragged into corners and piled untidily. Umbrellas that once offered shade have been tied up. Stands of lights droop. Four-leaf clovers still adorn some bars. St. Patrick’s Day was over two months ago.

Some downtown blocks are entirely empty. Moss grows on bricks. Bird poop and grime fill the sidewalk areas that vibrancy used to. Hand sanitizer dispensers wait inside doors. Upside-down stools hide behind dusty, boarded-up windows. Signs are taped to them, some professionally printed, others hand-drawn; some advertising delivery and carryout, others promoting GoFundMes or saying: Sorry, we’re closed. At Daley’s, Chicago’s oldest restaurant, a South Side staple for over 100 years, tables are half-set, but windows are dark. On Sunday afternoon, a used light-blue surgical mask rests on pavement just outside the front door.

As of Wednesday, restaurants had reopened, in some form or fashion, in 41 of 50 U.S. states. Illinois was not one of them. Last week, Gov. J.B. Pritzker announced limited outdoor dining would be permitted starting May 29, and Chicago restaurateurs perked up. The following day, Mayor Lori Lightfoot said the city wouldn’t be ready until next month, and those same restaurateurs bristled. They spent the long weekend somewhere between frustrated and confused. On Tuesday, they received mayoral guidance, in the form of a 13-page document outlining necessary safety measures. On Thursday, they finally received a reopen date – June 3.

In the meantime, they’re forging ahead in what a few call “survival mode.” They’ve redone menus, and devised meal kits, and dreamt up thematic dessert boxes, and advertised affordable family specials. With carryout and delivery their only options, Chicago restaurateurs interviewed for this story said they are operating on anywhere from 30 percent to 5 percent of standard revenue. Paycheck Protection Program money has helped some stay afloat. “But in real terms,” says Paul Fehribach, owner of Big Jones, “we’re losing $10,000 a week. Right now, the PPP is eating that. But once the PPP is used up, who knows where we’re gonna be.”

Imperial Lamian, an upscale Chinese spot, was among many Chicago restaurants that temporarily closed to cut costs. It recently resumed carryout and delivery – “so people know that we didn’t completely go out of business,” general manager Gerardo Bernaldez says – but with curtains pulled down, and the dining room deserted, and only four of roughly 60 employees working. Restaurateurs everywhere worry about those unlucky employees, the ones who saw jobs vanish in March. Many filed for unemployment. Some, such as undocumented immigrants, couldn’t and are struggling.

With partial reopening near, some managers, like Bernaldez, have initiated conversations with employees about returning to work. Responses have been mixed. Some servers wouldn’t feel safe, and are more comfortable living off unemployment checks than low wages. Bernaldez, therefore, keeps the discussions informal – because the moment he makes a formal offer to an employee, their eligibility for unemployment evaporates.

Other preparations are underway as well. Some restaurateurs have realigned tables to satisfy distancing requirements. They’ve thought about everything from layouts to disposable menus to pre-set tables. They’ve stocked up on masks. Bernaldez has requested quotes from cleaning companies for regular disinfectings. Donnie Madia, partner at One Off Hospitality, has developed a three-part playbook to offer patrons reduced face-to-face interaction with servers: 1. Make your reservation online by selecting a specific table; 2. pre-select your menu items; 3. pre-pay, in part or in full, if you want.

There’s significant concern among some owners and managers that Chicagoans will be hesitant to return to restaurants even when allowed to. Others grasp at optimism, and envision revamped hospitality; improved customer service; long-term changes for the better. But then they look around at the immediate-term. They see restaurants closing permanently. They see friends losing jobs. For Chicago’s 7,000-plus restaurants, they see no clear path forward.

Bernaldez has been working in the industry since he was 14, and its current state hurts him.

“I’m actually shocked, I’m a little sad,” he says. “I feel a little bit hopeless sometimes, and helpless. Like, what can I do?”

— Henry Bushnell

LOS ANGELES

Visit two Southern California beach communities over Memorial Day weekend, and you won’t find many similarities besides the cloudless weather.

In the Belmont Shore neighborhood of Long Beach, masks are the norm, foot traffic is sporadic and parking spots are unusually easy to find. Some of the area’s most popular bars, restaurants and coffee shops still have the same “temporarily closed” signs on their front doors that they did two months ago.

A little more than 10 miles south in Huntington Beach, it’s easy to forget the COVID-19 outbreak is still a concern. Restaurant patios on Main Street are packed with diners. Traffic is backed up for blocks. Sidewalks teem with unmasked pedestrians, while swarms of beachgoers enjoy the sand and surf.

The reason for the discrepancy is a combination of infection rate, politics and geography.

Long Beach is in Los Angeles County, which accounts for nearly half of California’s more than 90,000 confirmed cases of the coronavirus and has the state’s most stringent shelter-in-place laws. Huntington Beach is in neighboring Orange County, which reopened its retail shops and in-restaurant dining rooms over the weekend after passing benchmarks set by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“It’s two different worlds,” said Mike Simms, owner of a restaurant group with one Orange County location in Huntington Beach and nine others in Los Angeles County.

“If you’re in L.A. County, you’re looking at one set of numbers. If you’re in Orange County, you’re looking at another set of numbers. It’s just a completely different mindset that results from those numbers. In Orange County, they’re very willing to go out. In L.A. County, the level of confidence isn’t nearly as high.”

At the Huntington Beach Simmzy’s owned by Simms, the return of in-restaurant dining resulted in a huge turnout. Simms said the Sunday and Monday crowds at the beach-themed gastropub were “emblematic of a pretty normal Memorial Day weekend.”

To adhere to county-wide protocols and ensure the safety of customers, the Huntington Beach Simmzy’s removed half of its indoor tables and spaced the remaining ones 6 feet apart. The restaurant made up for that by securing permission from its landlord to extend its outdoor deck to make room for 10 extra tables with an oceanfront view.

Simms asks restaurant staffers to wear masks and gloves at all times. He even appointed a chief cleaning officer responsible for making sure that every table is sanitized once customers leave.

“The guests that were there last weekend were going to go out to eat no matter what, but there are a good chunk of people who aren’t going to go out until they feel it’s safe,” Simms said. “We want to project to them that this is a very safe environment to enjoy lunch or dinner.”

There’s no timetable for restaurants across Los Angeles County to be able to offer more than takeout or delivery, but some are optimistic that may soon change.

On Tuesday night, the Los Angeles Times reported that the county intends to present new data reflecting that it has met the state’s criteria for containing COVID-19. Even if that fails, the county could also apply to the state to allow cities with low infection rates to reopen before those with more confirmed coronavirus cases.

For now, restaurant owners across Los Angeles County are relying on creativity to stay afloat without dine-in service. A Culver City restaurant is selling heat-and-eat “TV dinners,” from Salisbury steak, to vegetable lasagna, to chicken parmesan. A Hollywood chef created a pulley system to lower her beloved breakfast sandwiches to customers from her fire escape.

Few Los Angeles-area restaurants have adapted better than Restauration, a Long Beach bistro that reopened in November 2019 after suffering fire damage the previous year. Owner Dana Tanner estimated that less than 5 percent of Restauration’s business came from takeout before March, but she quickly recognized the need to evolve.

Seasonal sangrias were one of Restauration’s trademarks, so Tanner shrewdly packaged that in mason jars and sold them for $17 apiece. Tanner also immediately began selling pantry essentials like eggs, flour and yeast to customers who couldn’t find them in the grocery store.

Meal kits that come with cooking instructions are among Tanner’s top sellers. So are prepared holiday meals like brunches for Easter and Mother’s Day or barbecue plates for Memorial Day.

“I tried to be innovative,” Tanner said. “What else can we do? What are people going to want?”

Even after COVID-19 recedes and normalcy returns, Tanner intends to keep selling signature items like burger kits, boxed pancake mix and to-go sangria.

“I would love my restaurant name in people’s cupboards at home,” she said. “You want to come here and make a day of it? Great. But I also want people to enjoy our dishes in their pajamas at home.”

— Jeff Eisenberg

Dining at the Olive Garden(s): Different cities, different experiences

As restaurants and states reopen in a patchwork fashion, there’s one thing almost all of America can count on: there’s probably an Olive Garden somewhere close by. With nearly a thousand locations across the country, it’s the closest we could come to a control group … so we all set out on searches for breadsticks.

Atlanta’s Olive Gardens are once again open for business … such as it is. Takeout has hummed along throughout the lockdown, but only recently have diners returned to the comfortable, sanitized Italian-lite dining rooms. It’s close to normal, but not quite there yet.

Dining out in an empty-when-it-should-be-full restaurant is a profoundly unsettling experience. The server is wearing a mask, and off in the distance, you can see another worker spraying and wiping down every surface that a diner might conceivably touch. Food is dropped off at your table like a hostage exchange, with everyone keeping their distance until the transaction is complete.

Give Olive Garden credit, it’s trying to spin a positive out of this, marking off tables with signs like, “Here for you always, six feet away for now” and “Social distance is temporary, family is forever.” But slogans can’t obscure how odd it all is to be back in a restaurant during a pandemic.

In Chicago, 20 minutes northwest of downtown, right off Interstate 94, the first Olive Garden novelty is a Bud Light-branded banner offering “beer, wine & seltzers TO GO!” With indoor dining in Illinois still far off, windows have been painted to advertise alcohol. A cheap turquoise folding table out back displays a $25 “berry sangria kit.” A makeshift bulletin board facing five curbside pickup spots is littered with beverage promotions as well.

But the slow trickle of customers mostly arrives for grub. Perhaps for the “buy one, take one” offer, which gets you two unglamorous entrees for significantly less than the price of one. Or perhaps just for the bread sticks. Two servers, both in masks, one in a quirky short-sleeve dress shirt and bucket hat, deliver containers of chicken parm and egregiously white spaghetti to driver’s side windows. They throw a few mint chocolates in plastic takeout bags for goodwill.

Out in California, at a time when Los Angeles’s family-owned restaurants desperately need support to stay afloat, corporate chains continue to suck up business. On a Saturday night at 6:30, there were at least a dozen cars occupying the 20 to-go parking spaces at the Olive Garden in Cerritos.

While Olive Gardens elsewhere in California welcomed dine-in customers over the weekend, this Los Angeles County location could still offer only takeout or delivery. A masked employee in a long-sleeved, button-down shirt stood guard at the front entrance to make sure no customers mistakenly came inside.

Orders arrived promptly despite the number of customers in the parking lot awaiting food. Within minutes, each car was on its way home with a to-go bag full of Americanized entrees big enough to feed a family of four.

There’s an expected sameness to the Olive Garden’s food, state to state. And maybe that — in addition to their sheer size — is why the Olive Garden, McDonald’s and other American culinary staples will weather the pandemic. When America comes out of lockdown, people won’t be looking for surprises, they’ll be looking for familiar comfort. And you don’t get any more familiar, or comfortable, than warm, fluffy breadsticks.