What is umami? Experts explain the 'mouthwatering' fifth taste

It's said that the man who discovered umami realized he was consuming a unique taste while eating a bowl of kelp broth.

We can only hope that the next great discovery comes to us over our own breakfast, but frankly, we're still working on truly understanding umami, more than 100 years after it was first named.

Food writers and recipe developers commonly reference it but rarely do we see this elusive (or is it all that elusive?) fifth sense explained for the average person.

So, what actually is umami and how do we achieve it?

Mushroom Miso Soup by Caroline Choe

Literally, what is umami?

There are four basic tastes besides umami: sweet, bitter, sour and salty.

Those four need no introduction, but umami is a bit harder to pin down.

"I usually use terms like savory and meaty," Nancy Rawson, the associate director and vice president of Monell Chemical Senses Center told TODAY Food. "It also has a bit of sense of fullness, like mouthfeel type of aspect to it as well. So it’s bringing a fuller flavor, a deeper flavor to food."

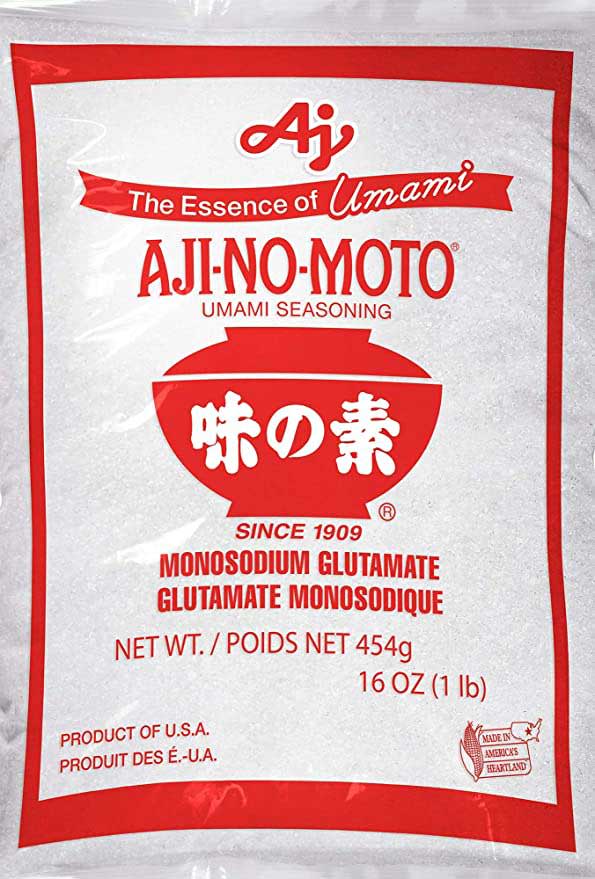

Ajinomoto, one of the largest producers of MSG (which we'll explain more about later) says umami taste "spreads across the tongue," provides a "mouthwatering sensation" and lasts "longer than other basic tastes."

Prawn and Chicken Fried Noodles (Mie Goreng Udang) by Lara Lee

Rawson said the long lasting aspect depends on the context, however.

"It depends more on the setting in which it is (used)," she said. "But that’s kind of the other really distinctiveness about umami, which is that it really is a sensation that almost has to be experienced in a context of a food.

She added that if you were to just add MSG to water and drink it, you'd get some sensation but it'd be very different than putting MSG in chicken broth.

"So it’s really a lot about how it’s interacting with the other flavor characteristics of the food," she explained.

Vietnamese Steak Salad by Michael Symon

The history of umami

The story goes that a Japanese scientist by the name of Kikunae Ikeda was enjoying a bowl of kombu dashi, or kelp broth, when he noticed the savory flavor was distinct from the four basic tastes.

In 1908, he named the taste "umami," which means "essence of deliciousness" in Japanese, and went on to study it, eventually isolating it in monosodium L-glutamate — or, as we now know it, MSG.

He went on to found a company that sold MSG in its purest form, Ajinomoto, which — as we mentioned above — is still very much in business.

The science behind umami

Interestingly, though MSG one of the first things that comes to mind for many people when discussing umami, it is not the only source of the flavor.

Umami can be found in our everyday foods. Aged cheeses, chicken, beef, onion, tomato, asparagus — the list goes on. As chef David Chang pointed out in his 2012 speech on the topic, Italians enjoy umami all the time when they eat spaghetti with Parmesan cheese.

Cacio e Pepe by Evan Funke

"That is one of the highest umami bombs you could eat," he said. "People tend to think that (umami means) salty but that’s because usually it’s in a dried fermented food product if you eat anything that’s fermented whether it’s fish sauce or fermented miso … that’s naturally going to be salty because that’s how you create it so it’s sort of one in the same so there’s salty, meaty flavor."

Now, to get really technical

When our body eats something with that salty, meaty flavor, our brains recognize what's going on. Alissa Nolden, an assistant professor of food science at UMass Amhurst, explained that umami is "from detection of glutamate."

Glutamate is an amino acid that is one of the building blocks of protein. It's naturally present in our bodies and occurs in food all the time.

"So we perceive this taste when a specific set of receptors are activated in our taste buds," she said, adding that two receptors form a pair to make the umami receptor.

Triple Decker Burgers with Cheese Sauce by Alex Guarnaschelli

“And so when glutamate interacts with the receptor, it releases ATP, and essentially signals to the brain, 'Hey, you’re, you’re perceiving umami,' and that’s called the gut brain axis," she said. ATP stands for adenosine triphosphate, which is a molecule that carries energy within cells.

"So your tongue is being activated by those receptors, forming a signal to tell your brain that hey, you’re perceiving umami.”

She said describing taste is difficult but umami is "kind of balancing perception. Kind of flavorful, but it it’s unique in own taste, and you can perceive it in the absence of salt which I think is one of the reasons why actually, umami took so long to become a taste.”

Grilled Salmon with Tamarind Dipping Sauce and Crispy Brussels Sprouts by Dzung Lewis

Wait, why did it take so long to become a taste?

Nolden said that even though Ikeda had coined the term more than 100 years ago, in the United States there's a "specific definition for something to be categorized as a taste."

"And so while the idea of umami has been around for a long time, it didn’t meet the definition of a taste, because they hadn’t been able to isolate umami by itself, meaning they couldn’t separate it from the other taste qualities," she explained. The U.S. didn't add umami as a taste until 1990 and it wasn't until the 2000s that scientists identified the actual receptors for umami.

"Even though this kind of word to describe that sensation had been long identified for over 100 years," she said.

Classic Pad Thai by Jet Tila

OK, but what about MSG?

So MSG, which is a seasoning, has been used for more than 100 years but in the late 1960s, a doctor reported in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine that he had experienced palpitations and numbness in his neck, back and arms after eating Chinese food.

In the years that followed, more anecdotal reports claimed to have experienced "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome." The phrase was even added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 1993 — though Ajinomoto successfully campaigned in 2020 to get the definition updated to include "sometimes offensive."

That said, the FDA says that MSG is safe and there have been no reputable studies that would indicate "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome" is real, Nolan said.

Herb Roasted Turkey and Honey-Thyme Gravy by Sohla El-Waylly

“There is no scientific evidence demonstrating (Chinese Restaurant) syndrome," she said. "It’s really unclear why (people would react) like that for MSG and not other sources of glutamate in our diet. So things like fish, and cured meats, mushrooms is another really common one. Other vegetables like tomatoes contain glutamate and things like fish sauce and soy sauce, and yet these things don’t seem to be associated.

"They’re really not being able to find any differences in the U.S. versus other cultures which may consume even higher amounts (of glutamate) than in our diet. So I think a lot of that is all anecdotal."

And, for what it's worth, MSG actually has 2/3 less sodium than table salt, Rawson said.

Rodney Scott's Famous Carolina-Style Ribs by Rodney Scott

"So it can be helpful if you’re trying to sort of generally reduce your salt," she said. "You can do it either with MSG or you could do it with Parmesan cheese or tomatoes or mushrooms or something like that as a way of really enhancing the overall flavor of the food."

She added that with so many people experiencing smell loss after having COVID-19, adding umami to their food might be a good idea.

"I think it’s helpful to realize that this is something that can kind of help overcome some of that reduced sensitivity to odors by making the flavor more interesting and more complex," she said.