Two women, worlds apart, and a rare disease that could offer clues about ALS

For more than 18 years, no one knew why Claudia Digregorio's muscles were slowly betraying her.

For Laura Keenan, the mystery lasted even longer.

Both women, in their 20s and living oceans apart, seemed perfectly healthy in infancy and early childhood. In Italy, Digregorio began falling at about age 3. In San Diego, Keenan's preschool teacher noticed her walking mostly on her toes.

By middle school, both were in wheelchairs suffering symptoms similar to middle-aged patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. The progression of ALS, the most common adult-onset motor nerve disorder, from first symptom to death can take just a few years. These girls advanced through early childhood, puberty, high school and into adulthood, their skills slowly ebbing away.

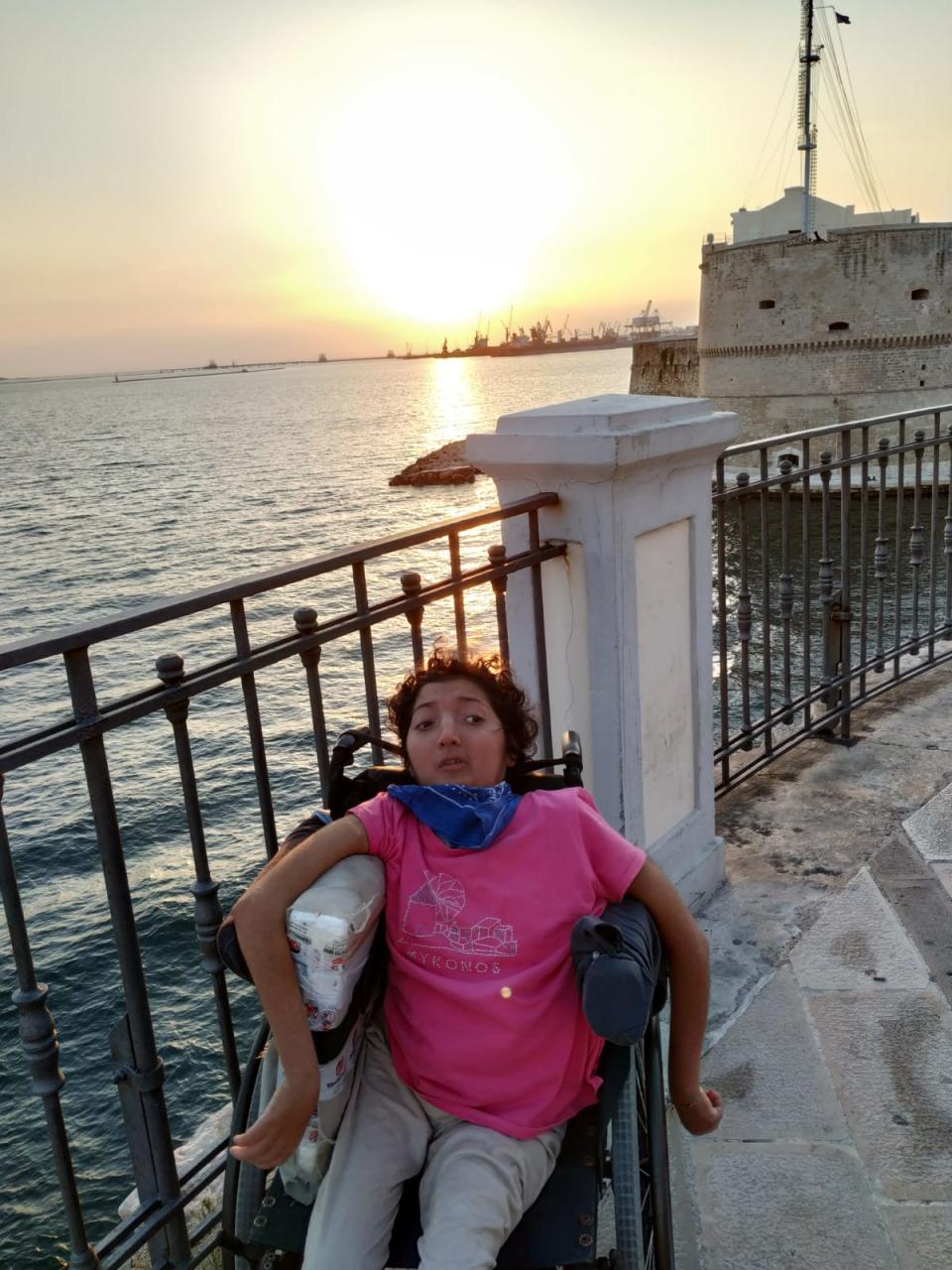

Digregorio, 22, was examined in nearly every major hospital in her native Italy. Then by doctors from London and Holland. No one had an explanation for what was wrong.

For Keenan, 27, of San Diego, "the torture began" with repeated testing. She was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, then spinal muscular atrophy. Neither fit her slowly declining physical state.

Without a correct diagnosis, no one could figure out how to help them.

More Choosing Hope: No answer can be the hardest answer. Why the fight to diagnose rare disease matters.

Digregorio's diagnostic mystery came to the attention of a police union, which paid her way to the USA in 2015 to be examined by doctors at the National Institutes of Health. Pope Francis gave her a personal blessing before she left.

The researchers, led by Dr. Carsten Bönnemann, identified a genetic spelling mistake they thought might be to blame for her symptoms, but they couldn't be sure because it was in just one person.

Two years later, trying to solve her health puzzle, Keenan's neurologist arranged for Bönnemann's team to examine her. Like so many doctors before them, they took blood and skin samples.

An analysis of Keenan's genes showed she had a similar mutation as Digregorio on a gene called SPLTC1.

Finding another person with a similar mutation on the same gene as well as the same symptoms was the "smoking gun" Bönnemann and his team were looking for. A global search of databases turned up nine younger people with similar symptoms and a SPLTC1 mutation in roughly the same spot.

Four of them inherited the genetic error from a parent. In DiGregorio and Keenan, the mutation arose on its own, shortly before or after conception.

Their condition still didn't make sense.

Different mutations in that SPLTC1 gene were well known to researchers because they had initially been found in six generations of one Pennsylvania family, who with age developed a disabling loss of feeling in their fingers, toes and skin. Why would a gene known to cause sensory neuropathy in some people trigger ALS in others?

Bönnemann and the team found the answer almost literally across the street.

Teresa Dunn had been studying the SPLTC1 gene for years as a professor at the Uniformed Services University, an arm of the federal government that sits across Route 355 from his lab in Bethesda, Maryland.

The gene, she explained, is responsible for making a fat-like substance that provides structure to support nerve cells. The Pennsylvania family's SPLTC1 genetic fluke triggered their bodies to produce a toxic protein that damaged their nerve endings.

The Digregorio and Keenan mutations lie on another part of the gene and lead them to overproduce this normal fat-like substance, damaging nerves and leading to their slow decline in muscle control.

"For me, it's a defining moment" making all these connections to a single responsible gene, Bönnemann said. "The power of really looking in detail at even a single patient with a rare disease and not letting go until the answer is found."

Their findings could also offer clues into more common forms of ALS, one of the most feared diagnoses in medicine.

"The fact that a very rare disease has provided insight into one of the most common diseases is, I think, striking," said Robert Brown, a neurologist and researcher at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, who discovered the SPLTC1 gene in 1998 and coincidentally has spent his career trying to understand and treat ALS.

Keenan said the discovery has given her more hope for her own future. Her mother, Susan Small, was relieved to learn the gene's identity. Her other three children don't have the mutation, so they aren't carriers of the debilitating disorder.

But the finding didn't change Keenan's daily life, which revolves around wheelchairs, breathing machines and family support.

She rides her exercycle every morning for an hour. Then she stands for another hour in a contraption her father designed to keep her upright. A self-described "Jesus freak," Keenan studies the Bible. Her beloved chihuahua Lizzee recently passed away at age 16, but her chihuahua-Jack Russell mix named Beanie Baby rides with her on her nightly outings.

"I have a wonderful life," Keenan said. "Jesus Christ gives me the hope I need to carry through."

Digregorio's days are even more constrained by her disease.

Although her mind is untouched, she can't speak more than a word or two at a time. Her parents, Concetta and Gaetano, can understand her, but it's hard for strangers.

Now that the diagnostic question has been answered, the real challenge, both families said, will be to find an effective treatment.

The therapy being tried by the Pennsylvania family, which triggers production of the fat-like substance, would be a disaster for Digregorio and Keenan. They will need a different approach to restore appropriate levels of the substance, said Dr. Payam Mohassel, an NIH clinical research fellow and the lead author of the team's study published this year.

"We especially want a therapy more than anything else," DiGregorio's mother Concetta said through a translator.

She's immensely grateful that although few people have the same mutation as her daughter, scientists are still working to find a solution.

"We have not been abandoned."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

More in this series

No answer can be the hardest answer. Why the fight to diagnose rare disease matters.

Decades-long quest to beat Fragile X fueled by persistence, science and relentless optimism

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: ALS patients could get answers from recent diagnosis of rare disease