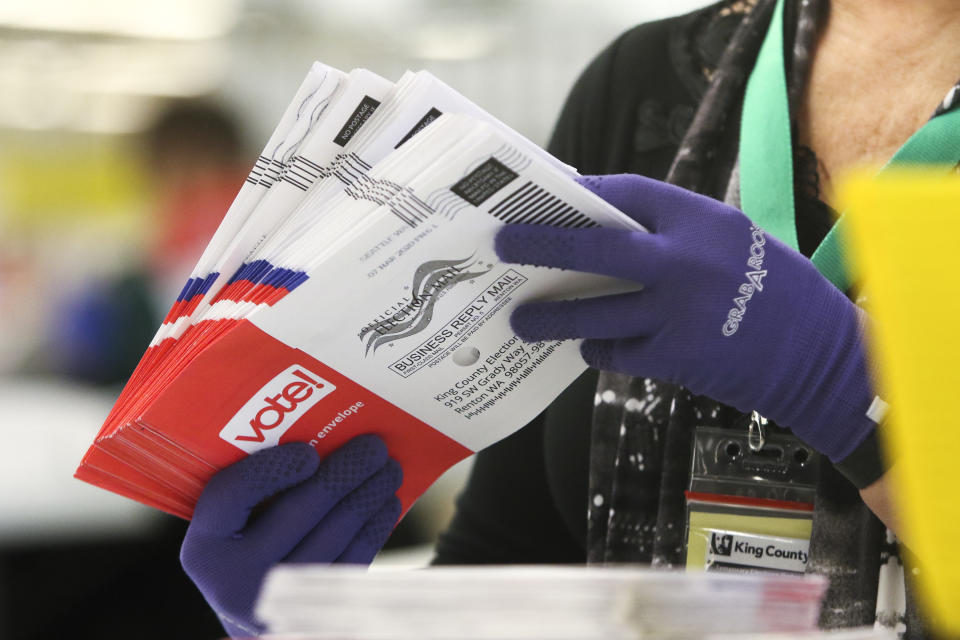

Trump's attacks on voting by mail haven't made a difference yet, but could in the fall election

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

President Trump’s repeated denunciations of mail-in voting have had little effect across the country yet, and most of the states still due to hold primaries this year are allowing their citizens to vote by mail.

But it remains to be seen whether some states that have expanded access to mail-in voting in response to the coronavirus pandemic might reimpose restrictions for the fall election if Americans grow less fearful of getting sick.

On Thursday, Trump continued to make inaccurate comments about voting by mail, telling reporters that “mail-in ballots ... lead to total election fraud.”

“We don’t want anyone to do mail-in ballots,” Trump said. He immediately clarified that some people could vote by mail if they are sick or won’t be in their state. Trump himself has voted by mail, both in the Florida primary this year and in the Florida 2018 elections.

“Now if somebody has to mail it in because they’re sick, or, by the way, because they live in the White House and they have to vote in Florida — they won’t be in Florida — if there’s a reason for it, that’s OK,” he said.

But even before the coronavirus hit in March, a majority of states allowed no-excuse absentee voting, or vote-by-mail. In all, 28 states and the District of Columbia already did not require a reason to request a ballot by mail, and five states conducted their elections entirely by mail-in ballot: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Utah and Hawaii.

And over the past two months, a majority of the 17 states where citizens had needed a reason to vote by mail have dropped that requirement.

In conservative states like Alabama, Kentucky, South Carolina, Indiana and West Virginia, in swing states like New Hampshire and Virginia, and in liberal states like New York, Delaware, Connecticut and Massachusetts, the government has created exceptions that allow residents to vote by mail.

In Texas, there is a court battle over vote-by-mail. A federal appeals court on Wednesday stayed a decision by a lower court to allow all Texans who want to vote by mail because of COVID-19 to do so.

Many of these states list sickness or disability as a reason to vote by mail, and a number have said that they are counting the COVID-19 crisis as a disability for voters under those provisions. Other states, like South Carolina, have said that during a state of emergency — which currently exists — residents can vote by mail in primary elections on June 9.

A number of states in March and April pushed their primaries into late May and June because of COVID-19. A handful have even extended into July, and Connecticut rescheduled its primary for Aug. 11.

However, many of these exceptions may not apply to the fall election. And that’s where Trump’s increasingly heated and inaccurate rhetoric could have an impact, especially if anxiety among everyday voters about contracting the virus declines.

Coronavirus news of late has been better than it was at the peak of the crisis, but there is significant uncertainty about how the virus will affect the nation over the summer and into the fall. The course of the pandemic over the next few months is, in many cases, likely to dictate whether the barriers to mail-in voting that have come down this year stay down or are put back up.

One conservative Republican state has already reinstated obstacles to voting by mail. After Oklahoma’s state Supreme Court removed the requirement that mail-in ballots be notarized, the Republican Legislature passed a law that put the requirement back in place.

Vote-by-mail has become increasingly popular among both Republican and Democratic voters over the last few elections, but Trump’s condemnation of the practice is in keeping with a broader GOP argument: that voter fraud is rampant and must be stopped.

But election fraud has been increasingly rare in recent decades, especially of the kind that Republicans most cite as a problem to justify strict voter ID laws: voter impersonation. The Brennan Center for Justice, a voting rights group at New York University, documented the lack of evidence for voter fraud in a recent fact sheet.

Myrna Pérez, the Brennan Center’s director of voting rights and elections, wrote a 2017 paper about ways that elections can be protected against fraud.

“The dangers come not so much from voter fraud committed by stray individuals, but from other forms of election fraud engineered by candidates, parties, or their supporters,” Perez wrote.

“Fraud, when it exists, has in many cases been orchestrated by political insiders, not individual voters. Even worse, insider fraud has all too frequently been designed to lock out the votes and voices of communities of voters, including poor and minority voters.”

In 2018, for example, North Carolina Republican congressional candidate Mark Harris hired a local operative who is accused of then overseeing a plot to steal absentee ballots and tamper with them. A new election was ordered, and Harris withdrew. The operative, Leslie McCrae Dowless, is awaiting trial.

Pérez wrote that “vote-by-mail raises election integrity issues because of concerns that ballots can be filled out improperly or manipulated for ballot stuffing.” In addition, the chances of a ballot being lost in the mail or damaged, or rejected by elections officials if they deem the signature does not match records on file, or because of some other voter error, are significantly higher than with in-person voting.

Pérez proposed making sure that mail-in ballots have bar codes that allow voters and the state to track the chain of custody. She also says state workers should get more training in “signature matching,” which is when a voter’s signature on file is compared with the one on their ballot to prevent fraud.

But Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine School of Law, wrote that “election design requires trade-offs.”

“Many states offer absentee balloting because they realize that the tremendous convenience to voters outweighs the small risk of fraud,” he wrote.

“Now, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic has radically elevated the risk of gathering at polling stations, making mail-in balloting a crucial alternative.”

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more: