Why scientists think there may be thousands of trees not yet identified

Trees are some of the largest and most widespread organisms on Earth, yet the true number of their species has been an enduring mystery.

This lack of knowledge is detrimental to conservation efforts. If scientists want to protect ecosystems, they must know the trees that compose and sustain them.

Now, new findings help illuminate the path forward. Scientists estimate that there are 14 percent more tree species on Earth than previously reported, according to a study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. An international team of researchers estimates there are roughly 73,300 tree species worldwide — and 9,200 are currently unknown to science.

“The results surprised and amazed us,” first author Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, an associate professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, said by email. “We could have never imagined that, even for trees, there would be so many species to discover yet.”

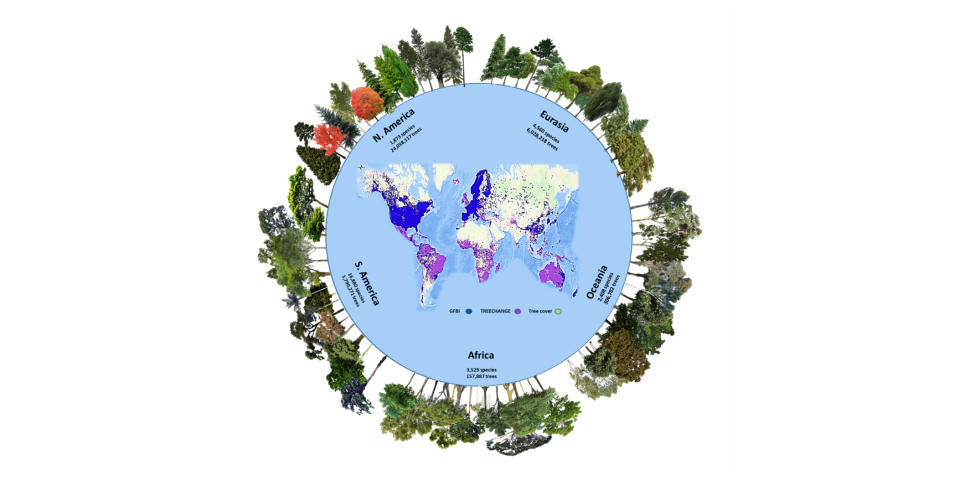

Gatti is one of the more than 100 scientists who worked on the study. The team utilized two global datasets, one from an initiative called TreeChange, a biodiversity project affiliated with Aarhus University in Denmark, and the other from the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative, a research collaborative that manages the world’s largest tree-level inventory database. This combination yielded a worldwide total of 64,100 documented tree species.

Then the team used artificial intelligence and a supercomputer to calculate the likelihood of tree species that are not yet identified. This process, which utilized a more extensive dataset and more advanced statistical methods than previous efforts, yielded a conservative estimate of 73,274 tree species.

Historically, tree estimates have been held back because local tree specialists were not included and the geographical focus was uneven, the team wrote. The number of tree species in higher latitudes is relatively well known. Meanwhile, other studies suggest the number of tree species consistently increases toward the equator.

It is in these more tropical and subtropical forests across South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania where scientists are more likely to eventually find undiscovered species. For example, South America is home to 40 percent of the overall number of tree species; the study team approximates that 3,900 tree species on this continent have yet to be formally identified and are clustered in the “diversity hot spots” of the Amazon basin and the Andes-Amazon interface.

These parts of the world have the greatest amount of unknown diversity, and the “species most vulnerable to loss,” said co-senior author Peter Reich, a professor and the director of the Institute for Global Change Biology at the University of Michigan.

“One of the take-home messages for the public concerning our study is there’s a lot we still need to learn about nature and the planet,” he said. “And much of what we don’t know is pretty critical for our ability to maintain and sustain human life, and the function of nature.”

Research suggests that forests, which fulfill numerous important functions, are more successful when they contain a greater number of different trees — also known as a higher level of biodiversity. A 2017 study published in the journal Ecology Letters found forests with many tree species grow at a faster rate, store more carbon and are more resistant to pests and disease.

Some of the critical functions of forests include, but are not limited to, providing a habitat for other species, facilitating carbon sequestration, supporting pollinators, protecting soil and improving water quality. Beyond enhancing climate resilience, forests represent “rich natural pharmacies by virtue of being enormous sources of planet and microbial material with known or potential medicinal or nutritional value,” according to a 2010 study published in the journal Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. The challenges to “delivering health through forests” are deforestation, biodiversity degradation and climate change.

“It is time humanity stops destroying biodiversity and increases global efforts to better protect it and improve our knowledge of its features,” Gatti said. “If we want to protect tree diversity and the amazing biodiversity connected to them, we should immediately halt deforestation and forest degradation, and start considering forests as untouchable ecosystems that deserve protection, like coral reefs.”

These findings add “urgency” to the known issue of threatened forests, Reich said. Undetected species and rare species are extremely vulnerable to the risk of extinction. A better grasp of how many of these trees exist can aid biodiversity preservation efforts. He acknowledges work is underway to protect forests via a number of avenues, ranging from the work done by grassroots organizations to governmental interventions, but he said “not enough is being done.”

Reich views these findings as what can be accomplished through passionate “international collaboration.” More work utilizing the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative dataset, which he helped create, is also underway: He and his colleagues are mapping out tree biodiversity across the planet, with the aim of understanding how it varies and what causes it to change.