'The Last Dance' writers' roundtable: So ... did the Bulls ever beat a great team?

The Yahoo Sports NBA staff watched the latest episodes of “The Last Dance” like the rest of you, and here were their responses to a few burning questions.

Did the Bulls ever beat a great team?

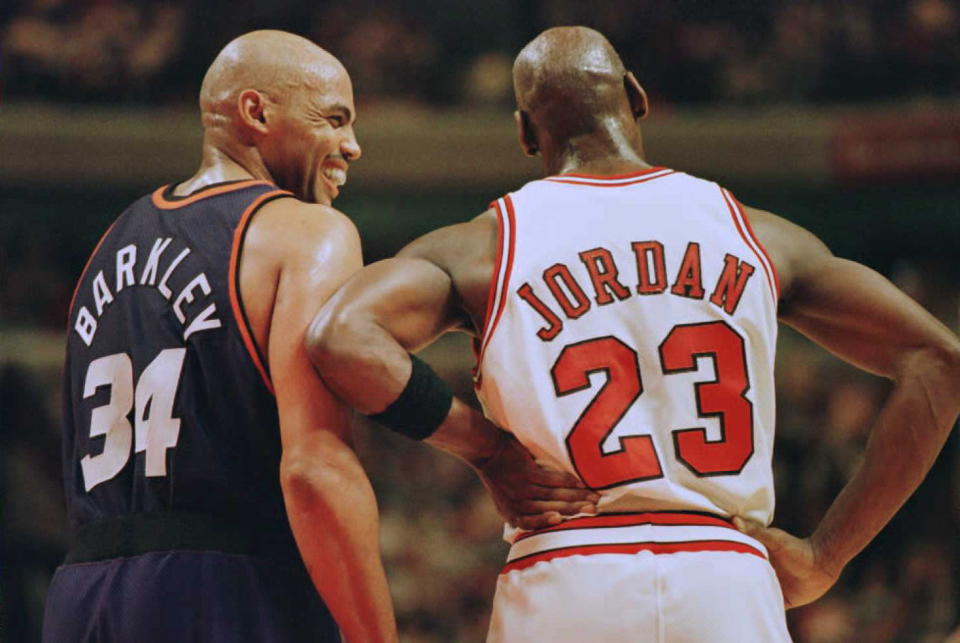

Vincent Goodwill: Expansion in the ’90s hurt the Chicago Bulls. Adding Orlando, Miami, Minnesota, Charlotte and, then later, Toronto and Vancouver, stripped away the depth and quality of teams in the ’90s. Even Magic Johnson’s 1991 retirement hurt in a way, considering the Lakers supposedly agreed to a trade for an MVP-type named Charles Barkley in the ’92 season. Imagine that type of matchup headed into the ’90s. The 62-win Phoenix Suns, headed by Barkley, seemed to be the best team Jordan’s Bulls faced. Those Knicks? They were tough, but the second-best player was John Starks. Not exactly Kevin McHale or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, or even a Finals MVP like Joe Dumars.

The valiant teams the Bulls went against seemed equipped with serious fatal flaws, and by the time Jordan fully returned from his baseball sabbatical, the Houston Rockets’ window had opened and closed with the best of Hakeem Olajuwon. The ’98 Indiana Pacers gave the Bulls their only seven game series past the 1992 playoffs, and the Shaq-Penny Orlando Magic were broken before fully maturing. If there’s a hole in the Bulls’ resume, name the third-best player on any team they beat in the Finals. Dan Majerle? Jerome Kersey? Detlef Schrempf? The clutch-and-grab ’90s kept scores closer relative to the Bulls’ superior top-heavy talent, and even though it’s no fault of their own, we didn’t see those Bulls fully challenged at full strength.

Chris Haynes: The short answer is probably not, unless you count that ’91 Los Angeles Lakers squad with an aging Magic Johnson. Of all their postseason foes and NBA Finals counterparts, not one of those teams classifies as a “great” team. But, to his defense, that was the part of Michael Jordan’s greatness: He never allowed the opposition to come within arm’s length of seizing control of the league in the ’90s.

The Houston Rockets are considered a great team after winning two titles during Jordan’s baseball experiment, but does anyone truly believe they would beat the Bulls if Jordan never left? The New York Knicks were postseason participants every season in the ’90s and made two Finals appearances. Had it not been for Jordan, do the Knicks grab a title or two?

The Utah Jazz, Portland Trail Blazers and Phoenix Suns probably believe they’re perennial champs had No. 23 played in a different era.

Seerat Sohi: I am going to defer to my wiser brethren for the most part here, but I do wonder if the NBA of the 1990s only feels watered down because Jordan was so dominant. History is never as objective as we’d like it to be, and popular lore rarely stops to compliment or even analyze teams that never made it to the promised land.

If you’re unlucky enough to fall into the orbit of a legend, even your accomplishments will fade into the footnotes of their story. Consider the case of Clyde Drexler, who as a member of the Portland Trail Blazers, and was considered one of the best young players in the NBA, alongside Jordan. In Episode 5 of “The Last Dance”, modern-day Jordan reveals he “took offense” to the comparison. That’s Jordan’s prerogative. Kawhi Leonard and LeBron James probably feel that way about each other, but that’s never going to stop the masses from comparing them. Forget the fact that Drexler is a 10-time All Star, a five-time All-NBAer, a Hall of Famer and even an NBA champion. Nope. He’s just the guy who was never as good as Jordan.

To frame Jordan as a winner, everyone else has to be a loser — even if they won: The “Bad Boys” Pistons, the Stockton-Malone Utah Jazz. You’d think, in hindsight, that Jordan made Drexler look pathetic on every play, that Charles Barkley, an MVP, never got a bucket on him. To Jordan’s credit, it’s not like he afforded them many opportunities to win. Maybe it’s actually a testament to the Bulls’ greatness that they consistently made their competition look bad.

Consider this: Even the most enduring champion eventually falls prey to the bullseye on his back. In the ’90s, teams stockpiled bulky big men and wings who could rough the game up against Jordan and Scottie Pippen. Patrick Ewing’s Knicks were a progeny of the “Bad Boys” Pistons. Barkley even teamed up with Drexler and Hakeem Olajuwon on the Houston Rockets in the late ’90s.

The Bulls’ opponents had their chances. They had a decade to scout and retool, but they never got over the hump. That could say more about Jordan than it does about his competition.

Was Michael Jordan’s gambling an issue?

Goodwill: His gambling was only an issue if we account for the shady characters he hung around. Richard Esquinas seems like a particularly sterling fellow to associate with, a so-called friend who wrote a book to expose Jordan’s gambling under the guise of “helping a friend.”

But the obsession with all things Jordan did appear to go a bit overboard. The man was a competitive junkie, going as far as flipping coins with his security team during his last year in Chicago. In 1993, Jordan went with his father to Atlantic City on an off-night. It should’ve been a minor footnote. His media boycott during the conference finals foreshadowed his October retirement, and if he should’ve been more discreet about his off-court endeavors, it was a lesson learned. Simply because he was Michael Jordan, the most famous athlete on the planet, gambling in a casino was frowned upon. Call me naive, but when is blackjack or roulette a black mark on someone’s character?

Jordan perhaps felt his generosity to the media earned him a bit of a pass on such matters, but when he shot 12-of-32 in the Game 2 loss to the Knicks ’93, the halo was stripped. In some roundabout way, it started the separation between media and athletes that exists today. Far more athletes control their message, as opposed to trusting relationships with media members. Although the players may not know it directly, the downhill cycle began with Jordan in 1993.

Haynes: Gambling was taboo back then. And with the scrutiny Pete Rose faced in Major League Baseball by placing bets on his sport just a few years priors to Jordan’s “incident”, everyone’s antennas were raised when a sports figure was connected to gambling.

The concern for any player or coach was that if he or she were an active gambler, what’s stopping them from placing a wager on the sport they play?

As a society, views have since adapted to embrace gambling. But it was a rather silly episode Jordan endured at the time.

Sohi: Well, if you believe the mother of all conspiracy theories, it drove him out of the NBA.

But let’s stick to what we know for sure. To hear Jordan tell it to NBC’s Ahmad Rashad in 1993, wearing sunglasses in studio, he didn’t consider it a problem. Well, maybe a “competitiveness problem.” Jordan is certainly the GOAT at repurposing his flaws into virtues. Jordan said if it was a problem, he’d be starving and pawning off championship rings. But the $1.25 million debt Jordan allegedly owed to his golf buddy, Richard Esquinas, was chump change for the endorsement king of the world. And despite the typical radio show consternation over his trip to Atlantic City in the middle of a playoff series against the Knicks in 1993, gambling never got in the way of Jordan going 6-0 in the NBA Finals. Great athletes can have hobbies. Some even have addictions.

But the public litigation of his gambling habit did flare up Jordan’s frustrations about fame. Episode 6 of “The Last Dance” touches on Jordan’s growing ambivalence toward his megastar status. At one point, he said if he could do everything all over again, he would never want to be considered a role model.

Jordan’s gambling habit was the first crack in the pristine image that made him America’s premiere pitchman. It was one of the few times that the person didn’t live up to the persona. The stress of the potential consequences of a scandal was getting to him. At the end of the first three-peat, he said he was mentally exhausted. Winning brought the Bulls more relief than joy.

“The Last Dance” worked toward an explanation for Jordan quitting basketball. I don’t expect ESPN to address the conspiracy theories, but the documentary paints a picture in which the stress of Jordan’s gambling habit becomes the first meaningful consequence of the fame monster that would eventually cause him to recede from the spotlight. It took a toll.

Does Jordan’s pettiness change your impression of him?

Goodwill: Jordan has always been Petty Pendergrass, and it’s great for the world to see. Think of it this way: This is a Jordan-sanctioned piece of work, and so much won’t be included, for various reasons. But the man cannot help himself when trying to settle old scores.

Poor Isiah Thomas, a man who had the gall to beat Jordan in playoff series three years in a row, then not kiss his ring on the way off the floor in the ’91 conference finals. How dare he? Keeping Thomas off the Dream Team, if Jordan did, was over the line, and shame on USA Basketball for bowing down.

Jordan acts like a man who doesn’t have six rings and isn’t universally believed to be the GOAT. But to be the GOAT, you’ve got to create enemies. Clyde Drexler, LaBradford Smith, Jeff Van Gundy … they’ve all been front and center for MJ for reasons real and imagined. This is a window into a man who’s motivated by a few things and sent into a rage by the most minute slight.

He takes no prisoners and will taunt you mercilessly if he gets over on you. How many of us have friends we’d just like to shut up because they’re so annoying about winning? That’s Michael.

Haynes: Change my impression? Did we not watch Jordan’s Hall of Fame speech?

I actually love it. Jordan found ways to manufacture slights in order to sustain a competitive edge. Poor Jerry Krause. Poor Toni Kukoc. Poor Clyde Drexler. Poor Dan Majerle. Poor Reebok. Poor Adidas.

Poor Isiah Thomas? Well, that would be pushing it.

Sohi: No. We’ve seen Jordan be pettier. Sure, he calls former general manager Jerry Krause “Crumbs”, but that’s nothing compared to his Hall of Fame speech.

Jordan eventually accepted Krause trading his enforcer and friend, Charles Oakley, for Bill Cartwright. But first, he spent a year calling Cartwright “Medical Bill” because he was injury-prone and throwing hard passes at him because he wanted to prove his theory that Cartwright had bad hands.

In the 1987 NBA draft, Krause drafted Horace Grant instead of Joe Wolf, a Dean Smith favorite who played at Jordan’s alma mater, North Carolina. Jordan called Grant a dummy, to his face, for years.

Some of the most driven people in the world are also the most unsatisfied. Jordan has had some ugly moments in the documentary, but we’ve seen uglier.

More from Yahoo Sports: