The killing of Elijah McClain and the silent crisis of racism in suburban policing

One officer “choked, slapped, and slammed” a 12-year-old Black girl, whom he also insulted with an ugly racial slur, according to allegations contained in a legal filing. After being involved in another, unrelated incident where he was accused of racism, he lost his job, only to win it back after an appeal. He remains a member of the police department in Aurora, a suburb of Denver.

Also on the Aurora police force is the officer who in 2003 killed Jamaal Bonner, an unarmed Black man. And the officers who in 2010 violently confronted Rickey Burrell, a Black man who was having a seizure. The department eventually settled a lawsuit filed by Burrell, who accused officers of fracturing his wrist and injuring his back.

The Aurora Police Department has recently been in the news for what happened on Aug. 24, 2019, when three of its officers tried to arrest Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man who was walking home from a grocery store. The officers choked and then restrained McClain, ignoring his cries of distress. Emergency responders injected him with ketamine instead of offering medical help, which McClain desperately needed and would not get in time. He suffered cardiac arrest and died two days later.

“Aurora’s persistent racist brutality is so widespread that it has been very difficult to catalog all of the examples,” says Mari Newman, a civil rights attorney who is representing the McClain family. Though she has represented them from the start, only now has the case attracted the kind of national attention that could lead to justice.

Eight years ago, Aurora was the focus of national sympathy after a gunman killed 12 people at a midnight film showing. The site of the massacre was 3 miles due south from the spot where McClain was killed. At that time, Aurora became the symbol of a culture drenched in gun violence. Now it is a symbol again, this time of another culture out of control: suburban policing.

Some progressives have held up suburbs as police-free zones, wondering why inner cities cannot enjoy similar circumstances. “A lot of people cannot fathom what an abolitionist America looks like,” Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., recently said of the push to defund police departments and redirect money to social services. “Tell them it looks like a suburb.”

Only it doesn’t. The notion that policing is nonexistent in suburbs is inaccurate. The vast majority of killings by police occur in suburbs, not large cities, according to the news outlet FiveThirtyEight. In 2016, a study ranked the 100 biggest American cities on how frequently police officers use force; Aurora ranked eighth. Close behind were Anaheim, a suburb of Los Angeles, and Mesa, a suburb of Phoenix. The relentlessly scrutinized — and criticized — New York Police Department was near the bottom of the list.

“When you look at the numbers, there are about as many people killed in suburban areas alone as everywhere else combined. This is a huge issue,” says Samuel Sinyangwe, co-founder of the Mapping Police Violence project and author of the FiveThirtyEight analysis. “Big cities tend to be more progressive, politically,” Sinyangwe added. “While rates are going down in big cities, they’re actually going up everywhere else.”

In 2018, the Better Government Association and public radio affiliate WBEZ examined 113 officer-involved shootings in the Chicago suburbs over the previous 15 years. They found that officers were not disciplined in any of those instances. In fact, some of the “suburban officers saw careers flourish after being involved in a controversial shooting,” the multipart investigation found.

The majority of the 113 people those officers shot were Black.

This is a story that plays out regularly on suburban streets and in suburban counties across the nation. But because most police stops, even violent ones, don’t result in killings — let alone killings like McClain’s that become a national cause taken up by celebrities — the crisis of suburban policing has gone largely unexamined.

“Nobody reports on its, nobody covers it,” says DeRay Mckesson, the prominent racial justice activist affiliated with Black Lives Matter. Mckesson grew up in Catonsville, Md., just over the Baltimore city line. He watched reporters swoop in for the civil unrest following the 2015 killing of Freddie Gray, an unarmed Black man, at the hands of city police officers. Most of those reporters moved on, forgetting about Baltimore.

Mckesson wishes they had stayed, in particular to cover the use of force by the county police department, which has jurisdiction over Baltimore’s suburbs. Last year the county department was sued by the Trump administration for racist hiring practices. The move received some coverage, but nothing like the sustained reporting that followed the murder of Gray.

Trump has used fear of racial justice protesters to make suburban safety a campaign issue, deploying racialized language and imagery to suggest that white people living in the suburbs would be unsafe if Joe Biden, the former vice president, were to win November’s election. He has even said that Biden wants to “destroy our suburbs,” presumably a reference to defunding the police (which Biden does not support) and fair housing legislation (which Biden does).

Aurora is a case study in how the suburbs have changed over the years while suburban police departments have not. In some ways, those departments share Trump’s vision of the suburbs more readily than do many suburban residents themselves.

Suburban police departments tend to take “much more of a law-and-order kind of approach” relative to their urban counterparts, says Rebecca Neusteter, a scholar of policing at the University of Chicago. “Arrests in cities have gone down significantly over time, at least in some categories, whereas that has not been the case in some suburbs.”

And while suburbs have experienced rapid diversification in recent years, that change has not been uniformly welcomed. In some places, aggressive policing is not only tolerated but also actively endorsed, even as major cities like Minneapolis and Seattle call for radical reimagination of law enforcement. Neusteter describes a public hearing in a Washington, D.C., suburb at which a member of the public asked a police chief “why they don’t use force more.”

The suburbs are a place instantly recognizable but not easily defined. That makes it difficult to say what makes a suburban police department, a problem compounded by the fact that some suburbs are policed by countywide departments that answer to an elected sheriff.

Although no standard definition exists, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation there are 7,001 suburban police departments in the nation, out of a total 13,128 local departments. The FBI defines suburbs as cities with fewer than 50,000 people, though its calculation also includes county departments within large metropolitan areas.

It can take a killing like that of McClain to focus attention on a department that has deployed overly aggressive policing against people of color, according to civil libertarians and activists in the Denver area. And they have done so, those critics maintain, with what amounts to complete immunity.

The Colorado chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union filed a legal brief against the department in July — just as Colorado was opening a new investigation into the McClain killing — alleging on behalf of a different plaintiff that Aurora “maintained an explicitly unconstitutional biased-based policing policy that allowed officers to use race as a motivating factor in policing decisions.”

An analysis of police activity in Aurora by criminologist Lance Kaufman conducted earlier this year found that African-Americans were 5.5 times more likely than other people to have Aurora Police Department officers use force against them. They were 1.4 times more likely to be shot with a Taser, but were 16 times less likely than other races to injure a police officer during an arrest.

That last finding, Kaufman wrote in his analysis, was “statistically significant at an extremely high level,” proving that not only did Aurora cops use force more frequently against Black people, but that the use of force appears to be less frequently justified in those cases than in confrontations with any other group.

In 2015, for example, OyZhana Williams was shoved to the ground and tackled because she’d dropped car keys to the ground instead of handing them over to police officers, who had engaged in a tense encounter with her in a hospital parking lot. During a 2017 “welfare check,” Aurora police officers hog-tied Vanessa Peoples, a Black woman in her 20s, “so tightly that they dislocated her shoulder,” according to the Colorado ACLU filing.

Those complaints point to concerns long predating the McClain killing. In 2005, an Aurora officer shot and killed Naeschylus Carter-Vinzant for allegedly violating the terms of his parole. In 2009, an Aurora officer kicked Carla Meza in the head, breaking a facial bone. That officer was fired but managed to win back his job.

The Colorado ACLU says all of these incidents — in which the victims were all people of color — and the McClain killing constitute a “disturbing pattern” of the Aurora Police Department “using force against people of color that would not be used against similarly situated white arrestees.”

Aurora’s most notorious arrestee is James Holmes, a white man responsible for the 2012 movie theater shooting. He was apprehended by the Aurora Police Department without the use of force and is currently in federal prison.

“The unjustified killing of Elijah McClain by Aurora police is part of an ugly and long-standing pattern of racially biased policing in that city. In case after case after case, Aurora police unnecessarily escalate tension, fear and violence when interacting with people of color,” says Mark Silverstein, director of the Colorado ACLU.

“The tragic result is that in one of Colorado’s most racially diverse cities, people of color, especially Black people, feel threatened when interacting with the city officials whose job is to protect them and ensure their safety,” Silverstein says.

But whose safety are suburban police supposed to ensure? That question, of course, brings up another, more fundamental one: Who are the suburbs for?

Since the 1950s, when they were created to accommodate the postwar population growth, the suburbs have been “idealized by white populations,” says Andrea Boyles, a sociologist and author of “Race, Place, and Suburban Policing: Too Close for Comfort.” The continuing arrival in major Northern cities of Black people from the South only accelerated that shift, known as white flight. Then the civil unrest that shook many cities in the late 1960s all but completed the suburbanization of white America.

This is exactly what happened to Denver and Aurora, just as it did to Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, Chicago and Cook County and many other metropolitan areas where increasingly neglected city centers came to be surrounded by wealthy, white suburbs with safe neighborhoods, good schools and plenty of green space. Racist practices sanctioned by federal housing statutes made sure the initial home buyers were white.

(Though racial covenants are a thing of the past, some of the racist practices still exist in vestigial form: Westchester, N.Y., has continued to grapple with allegations of discriminatory real estate practices into the 21st century.)

African-Americans settled in a part of Denver called Five Points, a thriving community nicknamed the “Harlem of the West” in the 1920s. Martin Luther King came to speak in Denver in 1967, a year before he was assassinated. Although the city did not explode in the kinds of unrest that the nation witnessed in Newark and Detroit, televised images of burning buildings and federal troops on American streets hastened the shift of white populations to the suburbs.

No place was better positioned to take advantage of that shift than Aurora, which annexed land and built housing throughout the 1970s to welcome families fleeing the big city next door. As across much of the West, vast tracts of open land practically begged for development. One mall arose in 1971, another four years later. By 1980, Aurora was “recognized as the fastest growing city in the United States,” according to a city history. Ten years later, the city’s population was approaching a quarter-million people.

That population was, at the time, overwhelmingly white. But that started to change in the aughts, as middle-class Black families and young Black professionals looked to escape cities. “Every time a friend of mine calls to say they are moving to Denver, I tell them about Aurora,” a Black native of Denver named Ryan Ross told the Denver Post in 2012. The newspaper noted that between 2000 and 2010 there were 14,000 new Black residents in Aurora, representing the largest such increase in the state.

This phenomenon, known as Black flight, accompanied a return of whites to cities their parents or grandparents had fled. So while Washington, D.C., lost its Black majority in 2011, the suburbs of adjacent Prince George’s County came to be known as the city’s “Ward 9” (the district has eight wards, with Wards 7 and 8 being home to the preponderance of Black residents). Latinos also moved to the suburbs near places like Chicago.

Elijah McClain’s mother, Sheneen, was among those who moved her family to the suburbs, “out of a hope that it would be safer,” says family attorney Newman. “She was concerned about gang violence in Denver.”

Communities that had been white for two or three generations suddenly saw an influx of people of color. “White comfort seems to be prevalent,” says Boyles, “when Black folks are situated in the inner city.”

This was especially true as crime rose in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The reasons for that rise were complex, but the media often explained it as having resulted from the trade in crystallized cocaine, or crack. The drug’s inner-city purveyors were seen in the popular media as wanting to exploit white suburbanites for profit. That perception likely increased fears of African-American families — like the McClains — fleeing those very inner-city neighborhoods for the suburbs.

A 1994 report from the Department of Justice described a seemingly dire state of affairs: “Many urban communities are experiencing serious problems with illegal drugs, gang violence, murders, muggings, and burglaries. Suburban and rural communities have not escaped unscathed. They are also noting increases in crime and disorder.”

By that time, crime was actually declining in most major American cities, having peaked in either 1990 or 1991 across the nation. But like his Republican predecessors, President Bill Clinton wanted to project a tough-on-crime attitude, which he needed to win centrist support for his 1996 reelection bid. That imperative became especially urgent after the Republican rout during the 1994 midterms.

In the Senate, a comprehensive anti-crime bill was crafted by a skilled dealmaker who had long made successful overtures to the chamber’s conservatives: Joe Biden. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act sought to punish both violent and drug-related offenses more severely. Critics also say that it led to the mass incarceration of Black men.

A quarter century later, that vision of policing persists largely untouched, which is why the last two Democratic nominees for president have been hounded by the legacy of the 1994 crime bill. Only very recently have activists, reformers and politicians offered a new vision of criminal justice that has backing outside the usual precincts of the left. But what reform will actually look like — defunding the police, abolishing police departments altogether, devoting more money to community organizations — when it arrives in Washington, as it inevitably will someday soon, nobody yet knows.

At the very least, both McClain’s killing and Trump’s invectives about criminals coming for housewives have led the nation to think more deeply than it has for a long while about what cities are, and what suburbs are, and what it means for someone to truly belong somewhere. McClain seemed to belong in the suburbs. But on an August night last year, that came to count for nothing.

Even as Black people entered the suburbs, they did not necessarily attain the power to dictate decisions on the local level. In particular, local government remained a “stronghold” for whites, says Rayshawn Ray, a Brookings Institution fellow. Elected leaders, in turn, usually appoint fire and police chiefs, as well as other municipal officials. That means that even as some suburbs became more diverse, those suburbs’ power structures mostly remained white.

That became apparent after teenager Michael Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014. In Ferguson, like in many other St. Louis suburbs, growing Black populations did not lead to growing Black representation in government.

“Longtime white residents have consolidated power, continuing to dominate the City Councils and school boards despite sweeping demographic change. They have retained control of patronage jobs and municipal contracts awarded to allies,” wrote former Missouri state Sen. Jeff Smith in the New York Times, describing what was happening in Ferguson but also, as he noted, in suburbs all over the country.

This filtered down to interactions between individual Black residents of Ferguson and members of the police force who were supposed to protect them. The Ferguson Police Department used traffic stops to essentially turn minor infractions into a major revenue source. “Ferguson police officers from all ranks told us that revenue generation is stressed heavily within the police department, and that the message comes from City leadership,” a 2015 Department of Justice report on policing practices in Ferguson found, even as it declined to press charges against the officer who killed Brown.

It wasn’t just traffic stops, either. In her book on the largely Black suburbs to the north and west of St. Louis, the sociologist Jodi Rios cataloged infractions for which Black residents of those suburbs might incur a visit from the police: “the number of people around their barbecues, the types of music they listen to, the coordination of their curtains, the way they wear their pants, where they play basketball, how they paint their backdoors, where their children leave their toys, who spends the night at their houses, who parks a car in their driveways, and how they use their front porches.”

Rios goes on to argue that “cumulatively, this has led to what many residents express as a lifetime of indebtedness and fear, and a feeling of being trapped in a place they do not have the means to leave.” The promise of suburban living, in other words, was never extended fully to many Black families who had been captivated by that very promise.

What was true in St. Louis was true elsewhere in America, and even if the specific practices were different, a pattern was plainly at work in the suburbs, one that was made worse by the gap between the demographics of police forces and the populations being policed. Mckesson, the Black Lives Matter activist, says an unhelpful “public narrative” cast the suburbs as havens of safety that only someone from elsewhere could disturb.

“The only danger is coming from outside,” Mckesson says of that narrative. Police officers, in this Trumpian version of events, are working only to keep malevolent influences at bay. “The public narrative is that they are not the issue,” says Mckesson. The killing of McClain has challenged that belief, calling into question whether police departments as white as Aurora’s are effective in working with populations that are no longer uniformly white.

A 2016 analysis by Brookings scholars Alan Berube and Natalie Holmes looked at the racial composition of 122 suburban communities around the country. “Most secondary city and suburban police departments, it turns out, exhibit even larger diversity gaps than their nearby big cities,” Berube and Holmes found.

That lack of diversity has real-world effects. In Prince George’s County, Md., Black police officers alleged in a 2018 lawsuit that the county department “had a persistent problem of officers who engage in racist conduct (including abusive police practices), both towards Officers and Civilians of Color.”

That same year, the sheriff of Bergen County, which encompasses the wealthy suburbs of New Jersey, right across the Hudson River from Manhattan, resigned after he was found to have made racist statements.

“Police can easily come to a point where they have very little self-awareness,” says Brandon del Pozo, who was a precinct commander in New York and later served as the police chief in Burlington, Vt., and has written frequently on police reform. “They’re really insulated from a lot of accountability.”

He cites the lack of media attention as a problem. “Everyone’s hounding the NYPD for its data,” he says, but few journalists show a similar interest in numbers for suburban police departments. “Who is watching what they are doing?”

Elijah McClain could have been forgotten — but wasn’t. His plight resurfaced on the internet during the protests that followed the killing of George Floyd in late May. More than 5 million people have signed a petition calling for justice. That call has also been taken up online, as well as by politicians.

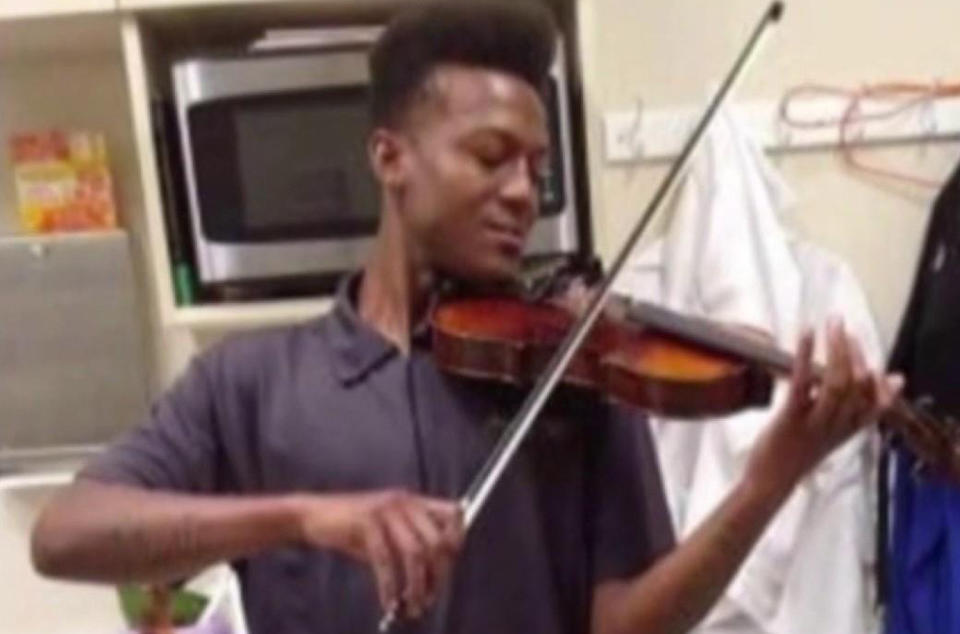

In an essay published after his death, civil rights icon and longtime Georgia congressman John Lewis called McClain a “gifted violinist.” At the U.S. Open earlier this week, tennis phenom Naomi Osaka wore a face mask emblazoned with McClain’s name.

Police in Aurora have responded to recent protests over the McClain killing by violently disrupting a peaceful demonstration at which several people played the violin. Three officers have been fired from the force in connection with mocking photographs taken at the site where McClain died. One of those officers, Jason Rosenblatt, had been involved in the attempt to apprehend McClain. The infraction that caused him to lose his job was responding to the offensive photograph over email with a “ha ha.”

Interim Police Chief Vanessa Wilson apologized for the photo, calling it a “crime against humanity.” Several weeks later, her officers stopped a car with five Black women. Guns drawn, the officers handcuffed them and ordered them onto the pavement. The officers believed the car was stolen. It had not been. Wilson promised an investigation. Her office did not respond to a request for comment for this article. Neither did that of the city’s mayor, Mike Coffman.

There are now five federal and state investigations into McClain’s killing and the Aurora Police Department. Late last month, McClain’s family sued 13 officers involved in the arrest, as well as a paramedic, a doctor and the city of Aurora itself. The suit charges that McClain was “terrorized” by a policing department that “permits and encourages a culture of racial violence.”

“This is a department that needs to be rebuilt from the ground up,” says Newman, the McClain family attorney. “The culture is rotten to the core.”

The text of the lawsuit she has filed against the Aurora Police Department opens with McClain’s final words, which were captured on the responding officers’ body cameras: “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe, please. I can’t. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe, please stop."

Cover thumbnail photo: Rich Fury/Getty Images

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: