This is the story of an HBCU civil rights wrong fixed 65 years later and the hope it offers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." – William Faulkner

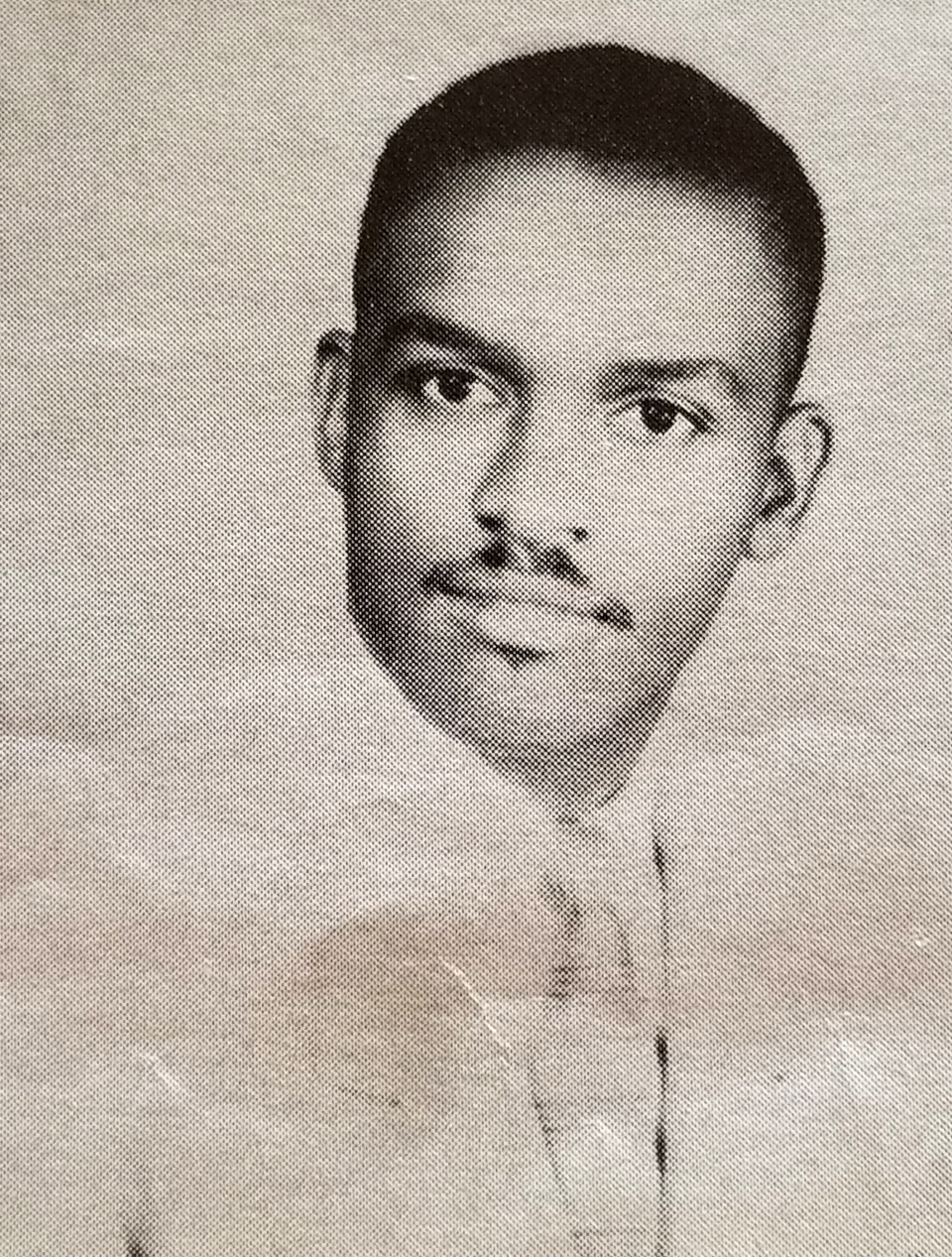

Earnest McEwen Jr.'s story is one of pain and triumph. Institutional repentance and ultimate redemption. A historical aberration and life-changing experience that should resonate with each of us.

After all, his is the story of an American dream – one initially stolen from a young Black man. It would only be rectified posthumously. Yet it is one that must give us hope in perseverance. In family. In accomplishment. In fight. And in healing.

McEwen received an honorary doctorate on Saturday from Alcorn State University – a degree he didn't earn academically but one he richly deserved. It took 65 long years for him to be recognized by the university that once shunned him.

Ousted for advocating for Black people

Allow me take you back to Lorman, Mississippi, in the 1950s. A time when Black women and men were fighting for rights and equality. A time where, in the South, those same Black folks were being rejected as human beings and hated for having the audacity to exist. At best, they were spit upon. At worst, they were lynched.

McEwen was student council president at Alcorn, then known as Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College. The school was established for African Americans – the first Black land-grant institution to receive federal funding under the Morrill Act of 1862.

Medgar Evers, who served as the first Mississippi NAACP field secretary, would become one of Alcorn's most notable alumni. Evers – who fought against Jim Crow laws, protested segregation in education and launched an investigation into the lynching of Emmett Till – was assassinated in 1963 by a white supremacist outside his home in Jackson.

Drum majors for change: Civil rights leaders of 1961 teach us to confront injustice

In March 1957, led by McEwen, nearly 600 students walked out of classes after demands for the dismissal or resignation of history professor Clennon King Jr., who wrote a series of pro-segregationist articles for The Jackson State Times that harshly criticized the NAACP, were ignored. In response, the all-white state college board ordered the students to return to classes; it threatened to close the school if they did not.

The students who refused to return to campus were considered expelled and barred from enrolling at any state school in Mississippi. Those students who decided to return to Alcorn had to sign affidavits vowing to never again participate in campus protests.

Six weeks before he was supposed to graduate, McEwen, who was studying to become an architect and ranked No. 1 in his class, was forced to leave campus within 24 hours for his leadership role in the protests. Because he refused to align himself with an institution – one created for African American students – that ironically didn't honor him or his Black peers, he and several other student council members were driven out.

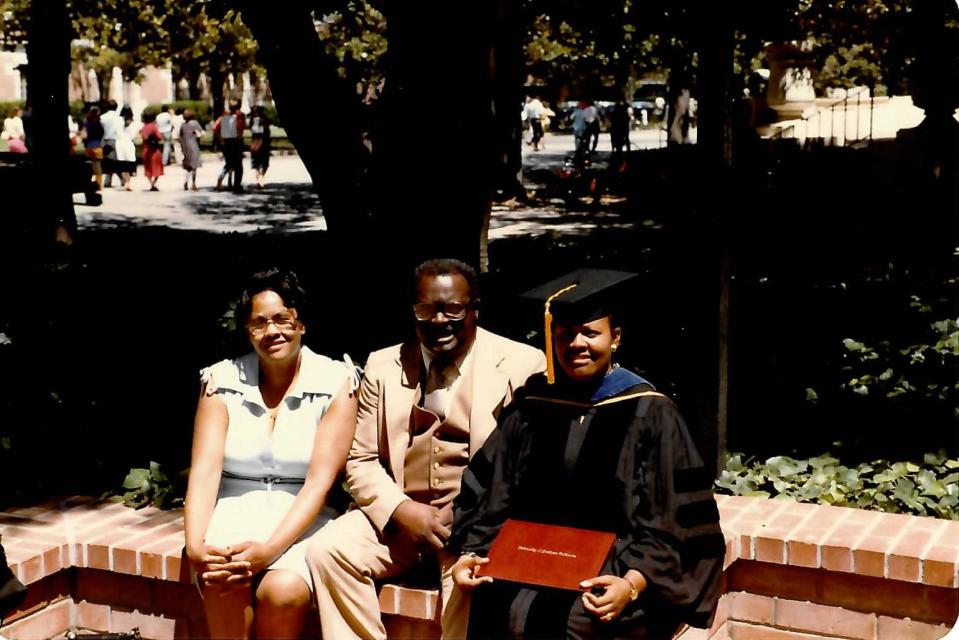

"My father's role – I'm going to say it was personal," his daughter, Gloria Burgess, told me. "He was representing his own personal beliefs about human dignity and birthright dignity of Black people, all people, and pushing back against what he believed to be the unethical stance and practice from this individual faculty member. It was also an institutional stance, if you will, in his role as the student body president. It was institutional in the sense that he was representing all of the students and became the voice for that. And so for his role, he was ousted."

But he would not be deterred.

William Faulkner championed the family

Before McEwen attended Alcorn, he worked as a janitor at the University of Mississippi in the early 1950s. As a Black man in Jim Crow-era Mississippi, McEwen dreamed of a college education. Because of segregation, he could work at Ole Miss, but he couldn't attend school there. Still, he was a noble man and one of great character and conversation. As he mopped the halls of Ole Miss, he would chat with the students, faculty and staff.

He told them of his aspirations and goals. He wanted to live in a house with running water. He wanted a better life. He vowed to achieve greatness, no matter the cost. Mostly, he bragged about his growing family and his desire to work hard to succeed – for them.

Columnist Connie Schultz: My front porch is my summer sanctuary. I find happy memories, hope and peace out there.

A professor who listened and cared introduced McEwen to Pulitzer Prize-winning author William Faulkner, who lived in Oxford, where Ole Miss is located. Faulkner immediately took to McEwen and gifted him tuition and room and board to attend Alcorn. Faulkner's only request: that McEwen pay it forward somehow.

"He also made sure that my sisters, my two older sisters and me, who were little babies at the time, had food and he had enough pocket money so that he wouldn't have to worry about stuff like that while he was studying," Burgess said.

A legacy of endurance and love

After the Alcorn walkout, McEwen and some of his peers who did not return to Alcorn transitioned to other historically black colleges. McEwen, with help from the NAACP, would complete his degree requirements later that year – with honors – at Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio. Others were unable to reengage, unable to achieve their educational dreams.

"Oftentimes, we look to the majority community as righting the wrongs of the majority community," Felecia Nave, Alcorn's current president, told me. "I think it's equally important that as an African American community where we've done wrong, that we also make every effort to correct those as well. And we shouldn't have to be cajoled into doing so. We should do it because it's the right thing to do."

Nave, an Alcorn alumna and the university's first female president, made the decision to honor McEwen with a posthumous doctoral degree after learning about his story from Burgess, who delivered the commencement address, and reading university archives. A bachelor's degree wouldn't be fitting for a man who fought for so much more. He paid it forward, indeed.

"I was just totally struck by just the bravery, the courage of her father, but also his persistence and his commitment to his educational attainment, as well as the commitment to his community," Nave told me.

Columnist Suzette Hackney: Finding my family's history in Brunswick, Georgia, where Ahmaud Arbery was murdered

After graduating from Central State with a degree in vocational education and a minor in mathematics and chemistry, McEwen moved his family to Detroit, where he worked again as a janitor at Detroit Osteopathic Hospital. While there, he taught himself hematology and built a career as a blood bank technician. Eventually, he became an engineer at Ford Motor Co. and earned a master’s degree in business from Central Michigan University.

His children have medical degrees and doctorates. His quest for education has been passed on. His desire for a better life – one built with his wife, Mildred Blackmon McEwen, 92, for those they cherished – has been achieved.

McEwen died in 1988, at the age of 56, after a long battle with cancer.

But the past is never dead. It's not even the past. For one glorious moment, let's celebrate Earnest McEwen's legacy of endurance and love. And what the future may hold for us all – those of us willing to listen and learn.

National columnist/deputy opinion editor Suzette Hackney is a member of USA TODAY’S Editorial Board. Contact her at shackney@usatoday.com or on Twitter: @suzyscribe

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Civil rights protester: HBCU rights a wrong 65 years later for student