Stargazing could soon be a thing of the past as satellites clog up space

The night sky will be “crawling” with satellites by the end of the decade, blocking out the stars and leaving astronomers unable to make observations or detect alien life, experts have warned.

There are currently more than 8,000 satellites orbiting the Earth - a four-fold increase since 2019 - and numbers are set to grow exponentially in the coming decades.

Some 400,000 satellites have been approved globally for Low Earth Orbit (LEO), with SpaceX alone poised to launch another 44,000 for its Starlink internet constellation.

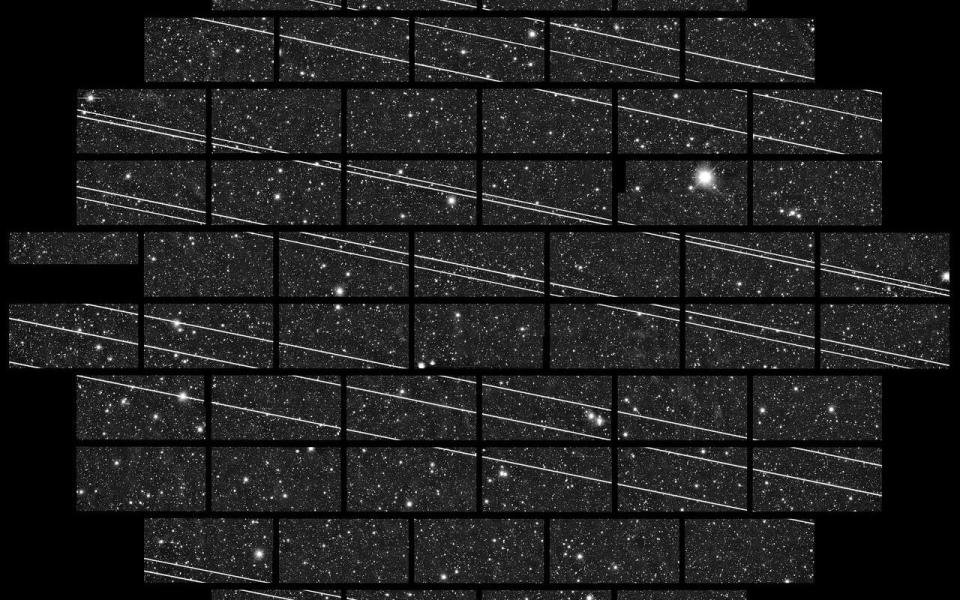

Satellites reflect sunlight back down to Earth, and already astronomers are struggling to deal with the bright streaks of light they create as they drift in front of the optical field of telescopes. Internet satellites can also interfere with sensitive radio telescopes.

Tony Tyson, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Davis, said: “If you just went out in a dark place somewhere and looked at the sky in 2030 it would be a very macabre scene.

“The sky will be crawling with moving satellites and the number of stars that you would see are minimum, even in a very dark sky. It’s a major issue.”

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), the UK Space Agency (UKHSA) and the Department of Business are so concerned they convened a Dark and Quiet Skies conference last week to call for regulation.

Dr Robert Massey, Deputy Executive Director of the RAS, said the world was seeing “a paradigm shift” in the use of space.

“There is the real prospect that we could see hundreds of thousands of satellites in orbit by the end of the decade,” he said.

“Frankly, searching for the origin of life may be a long shot but detecting signals from other civilizations becomes harder if you have an incredibly powerful and noisy sky.

“Unlike light pollution, you cannot get away from it, because wherever you are on Earth you can see the sky.

“If we leave this unchecked, I think this is also a cultural issue. If you get to the point where satellites make up, say about 10 per cent of the stars in the sky moving around, I think that’s fairly intrusive and it is a damage to that natural landscape.”

The $10 billion (£8 billion) Vera Rubin telescope, located on the Cerro Pachón ridge in north-central Chile, is already facing major problems because of satellites.

The telescope, which begins a 10-year survey next year, is looking for tiny changes in the movements of 37 billion stars and galaxies. Yet early testing has shown that around 40 per cent of frames will be impacted during twilight hours.

Even telescopes in space are facing difficulties, with images from the Hubble Space Telescope often ruined by over-saturation as reflective satellites go past.

The downlink beams from internet satellites are also millions of times more powerful than the sensitive sources radio telescopes are trying to detect, which could hugely hinder or confuse the ability to detect signals from space.

In 2021, a signal that scientists first believed was the ground-breaking discovery of a gamma-ray burst from the oldest known galaxy in the universe, was in fact a reflection of sunlight from the remnants of a Russian Proton rocket.

Not only would the glut of satellites damage astronomy, but it could change the night sky forever, experts warn.

Scientists are also concerned about the sheer number of de-orbiting satellites.

Ken MacLeod, an independent expert in what happens to satellites after they stop being functional, has calculated that when all the internet constellations are operational there will be around 16,000 decaying internet satellites at any one time that will need to come out of orbit.

“They will cause re-entry fireballs,” he said. “If we really believe the numbers of how many are going to be falling, that’s about 60 every day and that’s much brighter than magnitude 7 (the faintest starlight visible with the naked eye) so they can cause troubles with all those observations.”

Companies like SpaceX are now working to try and mitigate the issue, and are considering solutions such as black coatings or sun visors for their satellites.

So far none have proven effective and experts are calling for global regulation to limit numbers and make companies responsible for removing their old satellites from orbit once they stop working.

The twinkling canopy above our heads that has inspired so many is now under threat

by Sarah Knapton

The night sky is becoming dangerously overcrowded.

Hundreds of thousands of satellites are due for launch in the coming decades, with seemingly little thought given to the potential impacts.

This reckless saturation of space risks killing off ground-based astronomy, as well as destroying the gentle twinkling canopy above our heads which has inspired artists, musicians and philosophers for thousands of years.

But there are more reasons to be concerned.

In 1978, Nasa scientist Donald J Kessler predicted that when enough objects are in Low Earth Orbit, any collision would set off a catastrophic chain reaction which would send wreckage into the path of other satellites, breaking them apart and releasing more debris.

The subsequent swirling debris cloud of bullet-fast wreckage would make space inaccessible for everyone, and wipe out critical satellite systems.

“What happens is you get an exponential runaway where each little piece collides with another satellite which breaks up and each of its pieces,” Professor Tony Tyson, of the University of California, Davis, told delegates at a Dark and Quiet Skies Conference in London this week.

“And that lethal debris rises with time. It is clearly not sustainable.”

Constant battle to avoid crashes

Undoubtedly satellites are crucial for life today, allowing us to communicate and navigate over vast distances as well as monitor environmental issues and criminal activity. But their numbers are growing so quickly that it threatens those very systems that we so heavily rely on.

Kessler Syndrome is expected to kick in when there are between 40 to 50,000 satellites in orbit, and a recent US Department of Defense study predicted that above 40,000 satellites the chance of an exponential runaway effect is around 70 per cent.

So it is more than a little concerning that internet providers alone are planning to launch 100,000 satellites in Low Earth Orbit in the next decade.

The numbers in SpaceX’s Starlink constellation would be enough on their own to spark Kessler Syndrome, and once the company’s Starship spacecraft becomes operational it will be able to launch 400 satellites at a time.

The US aerospace company Astra is expected to launch 13,620 satellites while China’s SatNet is proposing a 13,000-strong constellation.

Even today, with fewer than 10,000 satellites in orbit, companies face a constant battle to avoid crashes.

OneWeb, the satellite internet constellation which has 542 satellites in orbit, said trying to avoid space collisions was like playing the 1980s arcade game Frogger - in which users had to direct a frog across a busy road.

“That arcade game with the little frog, this is what we actually have to do in real life,” said Maurizio Vanotti, Vice President of Global New Markets at OneWeb.

“We get about 50,000 messages a day from the satellites, and from that, we extract about eight to 10 instances where we have to manoeuvre in order to avoid the potential risk of proximity and collisions.”

Understandably, the prospect of satellites colliding is making insurers twitchy, with big names like Swiss Re pulling out of Low Earth Orbit in recent years.

Experts believe that Kessler Syndrome is now so likely that satellite companies may soon struggle to find anyone to underwrite their projects.

Professor Joanne Wheeler, an expert in satellites and space policy at Alden Legal, said: “Space debris and space traffic management have been a growing issue for decades and unless addressed will lead to orbits becoming unusable.

“Six space insurance underwriters have pulled out of the Low Earth Orbit space market, with more to follow, because it’s very hard for them to assess the risk. That’s not a good sign.

“There is a very real risk of Low Earth Orbit becoming uninsurable. We need to protect access to space, not just for now but also for the unborn generations.”

To date, nations have resisted attempts to bring in internationally binding treaties which would limit access to space, or ensure that defunct satellites are quickly brought back down. Currently, there are more than 4,000 dead satellites in Low Earth Orbit.

The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) has issued guidelines on preventing orbital break-ups and removing spacecraft after the end of their mission but most insurers believe they are not enough.

“There is an ever-growing concern that IADC space debris guidelines are insufficient,” said the Atrium Space Insurance Consortium.

“We’ve seen a number of space insurers start to decline business due to these concerns.”

Clean-up companies like Oxfordshire-based Astroscale will soon be able to bring down defunct satellites from space, and companies like OneWeb are already building docking plates onto their satellites in anticipation.

But experts say it will be too little to have much impact on overcrowding. It will also require sending more satellites into orbit.

Ken MacLeod, an independent expert in end-of-life satellites, believes that big constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink should be required to include “buddy satellites” which can service the tech and help it de-orbit.

He has calculated that there may be 16,000 satellites needing to de-orbit at any one time, once the 100,000 internet constellation satellites are in place.

“They could potentially collide with each other since they may have much less control and that could yield rapid changes in the debris catalogues and for the problems,” he said.

So can anything be done? Well, Britain is leading the way in persuading companies to take more responsibility and is planning to launch a “green satellite” kitemark for companies committed to keeping space clear of debris.

It is hoped that holding the kitemark will reassure insurers, and help companies unlock funding and speed up licensing.

George Freeman, the Science Minister, said: “The UK is insisting that the commercial space sector has to have sustainability built right into its DNA.”

Yet persuading companies to clean up after themselves will not tackle the sheer number of satellites due for launch in the coming decades. The skies as we know them are in danger of vanishing forever.

So the next time you have a crisp clear night with a sky full of stars, make sure you head outside and soak it in. It may not be like that for much longer.