'It ... spun out of control': Part 2 of HBO's Tiger Woods documentary gets personal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

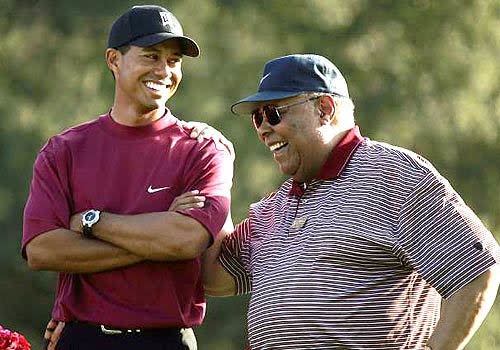

Jim Hill was only a couple of years into his sports broadcasting career at Los Angeles’ local CBS affiliate when his phone rang one night in 1978.

A deep voice on the other end of the line wanted to pitch a story.

“My name is Earl Woods,” he said. “And my son Tiger is getting ready to revolutionize the sport of golf.”

So began Tiger Woods’ eternal entanglement with celebrity and fame, the planting of seeds that would first sprout boundless popularity, then fuel severe public torment.

There’s a reason HBO was able to produce a two-part documentary about Woods — the finale airs Sunday night — without the cooperation of either him or many from his inner circle. His life has played out in the public eye, chronicled in great detail dating to when he first picked up a club.

And no matter how hard Woods tried to control his image, or how meticulously he and his representatives built up his brand, the spotlight on his life was just too bright. Eventually, even his darkest secrets proved impossible to hide.

“There was a disconnect between the Tiger that was being sold and the real Tiger,” Golf Magazine senior writer Alan Shipnuck said. “It just got larger and larger over time, then spun out of control.”

No one could see that coming when Hill picked up his phone more than four decades ago. Tiger was only 2 years old at the time, and Earl was just starting to form a grand vision for his son’s future.

“He said, ‘Before [Tiger’s] through, he's going to rewrite all the record books … and I want you to come down and do an interview with him,’ ” Hill recalled of his conversation with Earl.

Initially skeptical, Hill replied, ‘‘Well, what else is interesting about this story?”

Earl snapped back. “I’m a former Green Beret. Now get your butt down here.”

Hill, now one of the most recognizable sportscasters in Southern California, chuckled at the memory.

“You don’t get many phone calls that are like that,” he said. “This wasn’t a request. This was an order.”

When Hill showed up the next morning to do the story, he was amazed as little Tiger grooved perfectly straight shots and sank purely struck putts. The boy was charming during their interview too, hilariously answering one question by looking at Earl and saying, “I gotta go poo-poo.”

Once the story aired, it wasn’t long before Woods was a full-blown childhood star.

That same year, he made his first national TV appearance on the “The Mike Douglas Show.” By age 5, he was profiled in Golf Digest and featured in a segment by sportscaster Bryant Gumbel on the “Today” show. At 15, his picture was splashed across the pages of Sports Illustrated. And by the time he turned pro in 1996, he was being courted by corporate sponsors and media outlets of all kinds.

“He attracted people like 'Inside Edition' and stuff like that,” said Thomas Bonk, a former Los Angeles Times reporter who covered Woods’ early years on the PGA Tour. “Everybody wanted him, and he is not the most cooperative person to say the least.”

Indeed, by the time Woods arrived on the Tour, he already appeared jaded by the press and the spectacle of media attention. He wasn’t confrontational with reporters and never skipped his obligations at tournaments. But his answers were rarely engaging. His guard always seemed up.

"As writers go,” Woods said in a 1997 GQ profile, “you guys try to dig deep into something that is really nothing."

Ironically, that same GQ story, written by Charles Pierce and published two weeks before Woods’ first major championship title at the 1997 Masters, became a de facto “line of demarcation” in his relationship with the press, Shipnuck said, evaporating whatever goodwill he and his team had left.

The story captured a more candid side of a then 21-year-old Woods, including several off-color sexual jokes he said during a photo shoot. Though the piece made waves, Shipnuck recalled that “people just shrugged off the comments as sophomoric humor from a young kid” — especially after Woods’ record-breaking 12-stroke victory at Augusta National days later.

But, Shipnuck noted, “Him and Earl, I think, had always harbored the suspicion that people are out to get them, and that confirmed it.”

Instead, Woods went to work reframing his public appeal, presenting himself as both the ultimate competitor and personable family man.

His sponsorship with Nike spawned far-reaching marketing campaigns. He agreed with Golf Digest to become a “playing editor” beginning in summer 1997. He became a frequent guest on Golf Channel programming, sometimes even calling into the middle of its shows unannounced. And almost anyone outside of his bubble was kept at arm’s length, maybe two.

“It was the playbook of Hollywood stars,” Shipnuck said. “They were able to tell the story the way they wanted to.”

The problem was, that account became less and less authentic.

“The scandal for Tiger was that he presented himself as this paragon of family values,” Shipnuck said. “And America hates a hypocrite.”

“The scandal for Tiger was that he presented himself as this paragon of family values. And America hates a hypocrite.”

Alan Shipnuck, senior writer at Golf Magazine

Even before the infamous National Enquirer story of November 2009 that first revealed his marital infidelities, or his late-night car crash two days later, there were signs that Woods was quietly living a lie.

As former National Enquirer editor Neal Boulton describes in the “Tiger” documentary, the tabloid had come close to publishing a story about one of his affairs in 2007 before Woods’ representatives instead agreed to have him appear on the cover of one of its sister magazines, Men’s Fitness.

There were rumors at the time about Woods’ party habits near his home in Orlando, Fla., and during trips to Las Vegas. And even Sports Illustrated, according to a 2019 account from SI writer Michael Bamberger, was contacted around that time by two women offering to sell a story about one of Woods’ mistresses, Rachel Uchitel.

But to the public at large, the idea of Woods being anything but a faithful husband and model citizen bordered on blasphemous. So when the truth was revealed through one tabloid bombshell after another — his scandal was the New York Post’s cover stories for more consecutive days than the 9/11 attacks — the reaction went beyond surprise and disappointment. It was as though Woods had betrayed his fans’ trust.

“The No. 1 thing was that it ran contrary to his image,” Bonk said. “It damaged a lot of people.”

Echoed Shipnuck: “Don’t sell yourself as a family man driving a Buick and eating Wheaties and having the wife and the kids around on the green after you win and all that sort of stuff — and then turn out to have this whole secret, salacious life. What fueled the scandal was the shock and outrage, feigned or otherwise, that Tiger was not who he told us he was.”

It makes Woods’ legacy a tough one to reconcile, especially within a sport that’s been stamped by his indelible mark.

The documentary takes a stab at it, closing on the subtle personality changes that led up to his triumphant 2019 Masters victory: He was looser around the course, friendly to other players, more captivating even in his weekly news conferences.

“He went through the worst public shaming of the internet age,” Shipnuck said. “To be so publicly undressed and humiliated and have to go back out there and look these people in the eye day after day was absolutely brutal. It took him a long time, but he made it back.”

Those who have covered his career know he still craves privacy and remains ever-conscious of his public image. It just might be a better reflection of reality now — a more honest portrayal of a man who was forced to make amends for his own mess.

“He’s going to go down as the most dominant golfer ever,” Shipnuck said. “That’s gonna be the first paragraph of his story. But the second one has to be what was lost and what he brought upon himself.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.