Spotted owls pushed closer to 'extinction vortex' by Oregon wildfires

SALEM, Ore. — The Northern Spotted Owl was already struggling before 2020.

But this year's Labor Day wildfires brought another major blow to the iconic but fragile population of birds, pushing them closer to the "extinction vortex," according to top researcher Damon Lesmeister.

Wildfires kicked up on powerful east winds Sept. 7 and burned across almost a million acres (about 1,560 square miles) of forest in Western Oregon.

All totaled, the fires burned 360,000 acres (over 560 square miles) of suitable nesting and roosting spotted owl habitat in Oregon. Of that, about 194,000 acres (over 300 square miles) are no longer considered viable for the birds, according to U.S. Forest Service data.

"These wildfires were very impactful on spotted owls," said Lesmeister, the lead researcher on spotted owls for the Forest Service. "The sad truth is that the birds caught in the fire likely didn't survive — it was just moving too fast. So there will be a lot of direct mortality.

"It will take time to sort out the exact impact to the population, but it's significant just because their numbers were already declining pretty rapidly."

Northern Spotted Owls occupied an estimated 14,000 territories across the Pacific Northwest in 1993, three years after they were listed by the federal Endangered Species Act. Today, it's estimated they occupy just 3,000 territories — meaning a single male or breeding pair inhabit each territory.

Lesmeister said even 3,000 is optimistic based on his field studies, which use digital audio recorders spread across the forest to locate and track owls in Oregon's forests.

Wildfires become third reason for decline in spotted owls

Two things have fueled the decline, he said: the invasion of barred owls overtaking nesting sites and habitat fragmentation.

But wildfires have become a third and potentially devastating stress on spotted owl populations, particularly when they burn as hot as they did this year, he said.

This year's fires were rare in size and power, torching even old-growth temperate rainforest that might burn only once every few centuries. They're the very places spotted owls depend on.

"We have so few animals right now that a big loss from these fires could become destabilizing on the population as a whole," Lesmeister said. "Indications are that they're already in the extinction vortex in some places, and headed there in others. They're long-lived birds and will continue to hang on for a while, but we're not getting the level of recruitment into the population to sustain them."

Not everybody agrees that wildfires are fueling a spotted owl decline, and argue wildfire can improve habitat in the long-term.

Either way, the bird that became a hero for environmentalists and a villain for loggers in the Pacific Northwest is barely hanging on.

Barred owl invasion

The biggest threat to spotted owls recently has been barred owls, a genetic relative that originated in the eastern half of the United States.

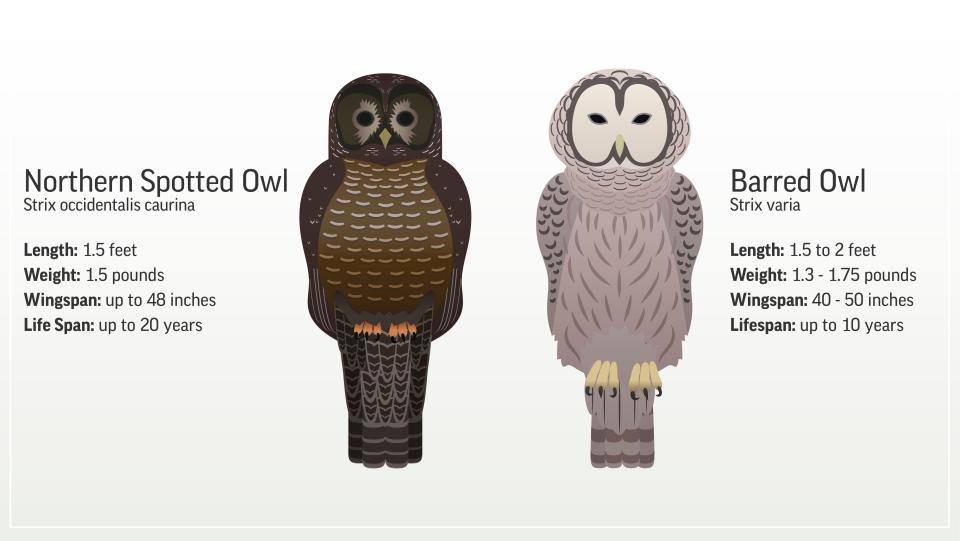

In appearance, they're similar to the spotted owl, except they're larger and instead of spots they have dashes or bars — hence barred owl.

Beginning in the late 1990s and expanding quickly in the 2000s and 2010s, barred owls began claiming spotted owl nest sites, out-competed them for food and even harassed and killed the smaller native birds. By 2010, it had become clear the invasion posed a major threat to spotted owls.

“When we first started doing spotted owl research, 50 years ago now, there were no barred owls in these forests,” Eric Forsman, the pioneer of research on spotted owls, told OPB. “Now they're virtually everywhere.”

Experiments have gone as far as killing 3,600 barred owls. That controversial program went on for four years but it's unclear what impact it had, Lesmeister said.

Habitat fragmentation

When spotted owls were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1990, it was largely because they were losing so much habitat due to logging in old-growth forest.

The birds live almost entirely in mature and old-growth trees, abundant logs and standing snags and prefer multi-layered canopies of forests at least 150 to 200 years old, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But those characteristics became increasingly rare, with suitable habitat reduced by over 60 percent over the last two centuries and particularly in the last 50 years.

Their listing, which paused all logging on federal lands by court order in 1991, turned the spotted owl into the hero or villain in the Northwest during the height of the so-called Forest Wars. They were used by environmental groups to halt timber sales of mature forests, becoming the poster-bird for the decline of a critical industry in Oregon.

The implementation of the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan did improve habitat on federal lands in the Northwest, Lesmeister said, but forest conditions on private and state lands have continued to fragment.

"Outside federal lands, the trajectory is still toward the loss of old forests," he said. "And taken together — barred owls, historic and new habitat loss and now wildfires, that's just a lot to overcome."

Some disagreement over impact of wildfires on spotted owls

A 2018 paper by Derek Lee, principal scientist at the Wild Nature Institute and associate research professor at Penn State University, questions the impact of wildfire on spotted owl numbers.

Lee looked at 21 studies of fire-burned landscapes and the impact on Mexican, California and northern spotted owls.

Instead of mixed severity wildfire being a bad thing, as most government agencies suggest, Lee asserted that wildfires don't impact spotted owl populations and in some cases improve habitat.

"The preponderance of evidence suggests wildfire benefits spotted owls, and therefore forest management should be promoting fire as habitat improvement for spotted owls," Lee said in an email.

Lesmeister strongly disagreed with the assertions of the paper and said a rebuttal worked on by 25 wildlife scientists was recently submitted for publishing.

He said the study takes generalizations from California wildfires and applies them to the Pacific Northwest, "which has vastly different fire regimes" and that "making assumptions about what happens with Northern Spotted Owls based on what is observed with California spotted owls is problematic," he said.

Lee said he only had one study that looked at the range of Northern Spotted Owls specifically, but said there wasn't evidence the response to wildfire was different in the two species.

Lesmeister disagreed.

Lee charged that the Forest Service's failure to recover spotted owls spoke to a need for new strategies.

"Maybe different perspectives and practices are needed," he said.

Northern Spotted owls disappearing from Washington

What has become clear is that Northern Spotted Owls are declining, particularly in the northern half of their range.

"We have very concerning key indicators, including inbreeding and seeing an increasing number of males and females that can't find a mate," Lesmeister said. "Indicators say they've reached the extinction vortex in Washington and British Columbia and are on their way in Oregon and northern California."

Lesmeister did note that more older forest could help in two ways — more habitat and forest that's typically less prone to high-severity fire.

But if 2020 proved anything, it's that wildfire can impact even the most ancient forest, leaving the spotted owl precious few refuges.

Follow Zach Urness on Twitter at @ZachsORoutdoors.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Northern Spotted Owl pushed to brink of extinction by Oregon wildfires