Shut up and run: Eric Dickerson on the history he made and the hurt that came with it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

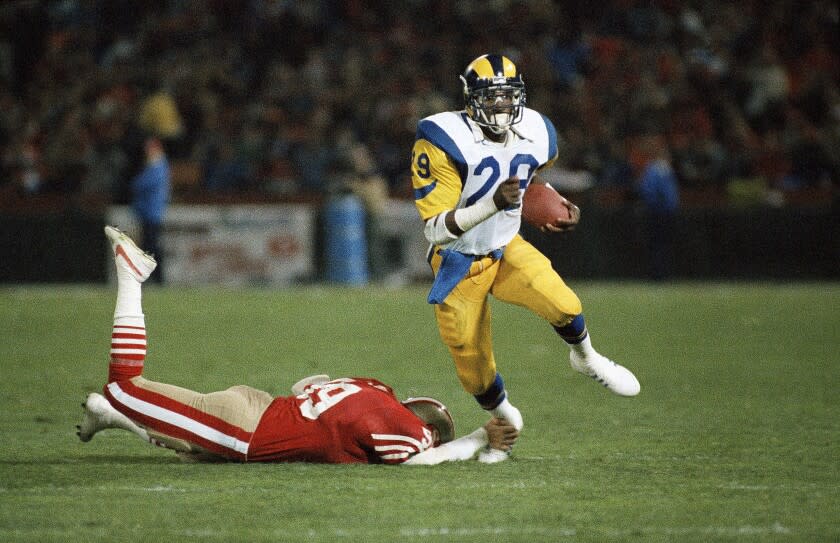

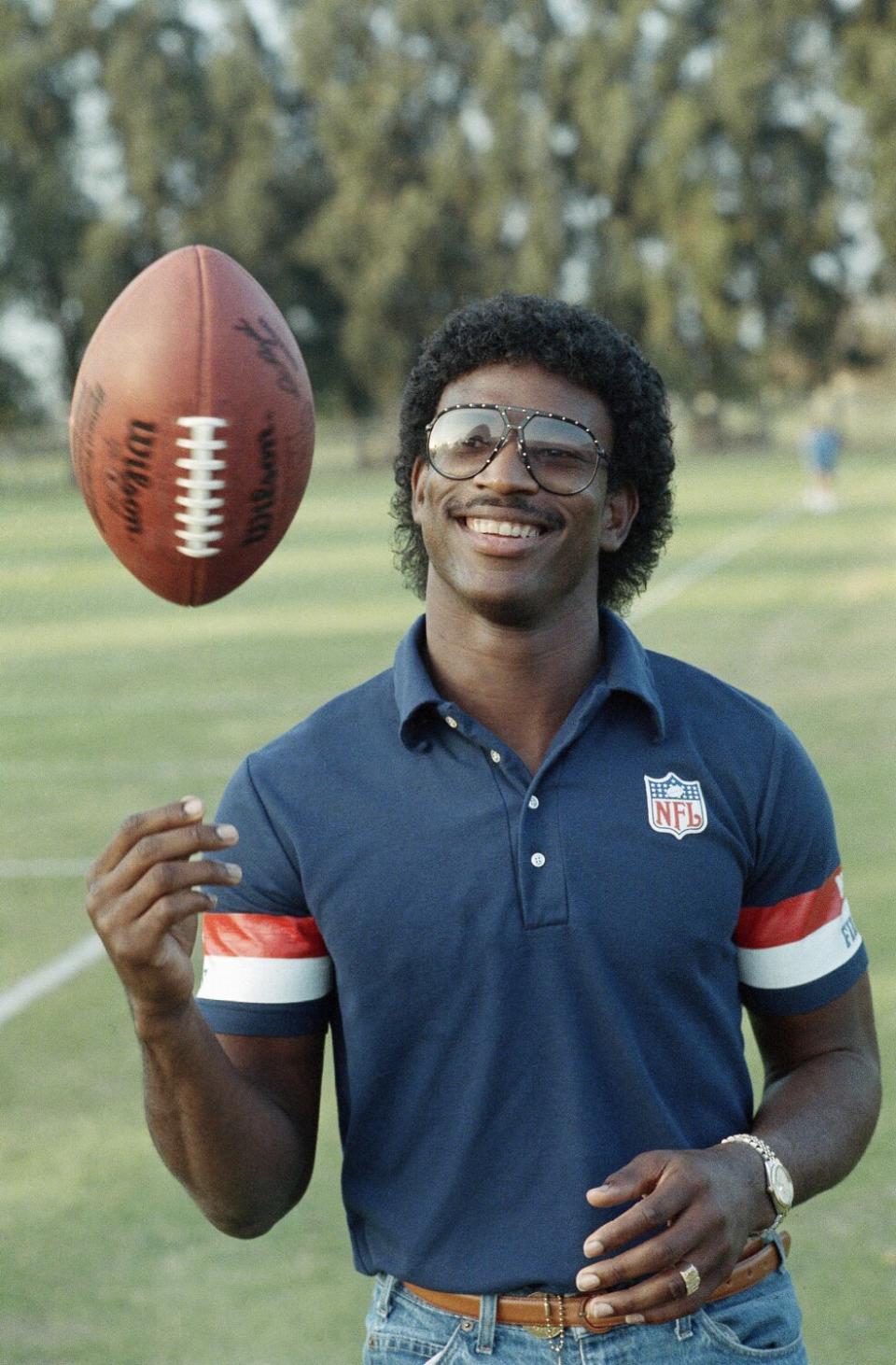

Three years into his NFL career, Eric Dickerson set the rookie rushing record (1,808 yards in 1983), the single-season rushing mark (2,105 yards in '84) and helped lead the Rams to the NFC Championship game ('85). Beneath the veneer of those accomplishments was an athlete at war with the power dynamic that remains at the heart of the NFL story nearly four decades later. In this excerpt from his forthcoming memoir, "Watch My Smoke," written with Greg Hanlon, Dickerson revisits the stalemate that would mark the beginning of the end of his relationship with his first NFL team.

I don’t remember the hit, but I remember lying on the field. I couldn’t get up. I couldn’t even move a limb.

Then I was in a wheelchair. People would visit me, with sad, pitying looks on their faces. One minute, they’d wanted to be like me. Now they felt sorry for me.

It was the most terrifying dream I’d ever had. I think it was my junior year of college at Southern Methodist when I had it. Ever since I started playing football, I’d been afraid of getting paralyzed on the field. But that dream made the fear worse. After that, the fear popped into my head every couple of months. As the years went by, it took more and more effort to push it to the back of my mind.

I once told a writer from Sports Illustrated that football isn’t a game, it’s a business. Scrabble is a game, I told him, because you can’t break your neck playing Scrabble. In football, it only takes one play. Every week, you’ll see that guy writhing on the ground whose career — or even life — is never gonna be the same. As a player, it’s not a question of whether that’s gonna be you one day. It’s only a question of when it’s gonna happen, and how bad it’s gonna be.

Before it did, I wanted to make some real money. Under my current contract, negotiated by an agent I later fired, that wasn’t happening.

The contract was for four years and $2.2 million, but my $600,000 signing bonus was actually a forgivable loan, and after I got traded to the Colts in 1987, the Rams decided not to forgive the loan. For the first two years of my career — the best two-year period a running back has ever had, statistically — I earned an average of $167,000 at a time when the top-paid backs were getting close to a million per. That’s not a team-friendly deal. That’s robbery.

By the end of the ‘84 season, my outlook about being a pro football player had begun to change. I was waking up to the way the league worked, no longer a wide-eyed rookie who was just happy to be there. The newspapers had started publishing players’ salaries, and I’d see what other guys were making compared to my salary. I’d see how the Rams treated their players. Like how they’d cut guys who got injured in the middle of the season. Like how team leaders and good players would get traded, because while it’s all about the team inside the locker room, it’s all about profit for the people upstairs.

And as much as I loved L.A. and my teammates, the organization was a different story. With Georgia Frontiere as owner, we all had the sense that the organization didn’t care if we won or not and that the focus was on protecting the owners’ money. For years, we were a playoff team — but the organization didn’t do the things, like get a good quarterback, that would’ve put us over the top. I had no problem with Georgia personally — she always struck me as a nice lady, and my mom and her got along — but it was obvious playing for the Rams that things were being done on the cheap, and that we weren’t a first-class organization.

Example: Our practice facility was a junior high school in Orange County, with a shabby field and showers that were way too short, so you had to duck your head to get it wet. Our meeting room was a cramped classroom at the school with not enough desks, so some guys had to stand. The desks were the small ones with the wooden top you’d fold over. It was ridiculous to watch 250-pound elite athletes cram into desks that 13-year-olds used to learn algebra.

Another thing that was weird: We’d get two different game checks, from different banks. Years later, I ran into a guy who said he was the Rams’ banker and we got to talking about it, and everything he said validated my impressions about the organization: He said the Rams were always cash poor, and were always moving money around to balance the books. He told me that when the Rams traded for Jim Everett and gave him his signing bonus, Jim’s check bounced.

My rookie year, Georgia paid for an interior designer to decorate my apartment in Irvine, with modern artwork, a zebra skin rug and a King bed with a velour headboard. It was nice of her, but after years of being underpaid, I came to think of it as a poor substitute for a fair contract. Because s—, I can decorate my own apartment. (Related to this, Adidas, my shoe sponsor, got me a cake for breaking the single-season rushing record in 1985. A cake. Except I couldn’t even eat it because it was a carrot cake and I’m allergic to nuts.)

Being in the same city as the Lakers and Dodgers underscored that the Rams were just not on par. Both the Dodgers and Lakers were premier organizations who won multiple titles in the ‘80s, and their owners were beloved icons in L.A. With Dr. Jerry Buss in particular, you could see the fondness he had for his players. Seeing the Lakers winning titles, and watching those guys make so much money and become big stars in L.A., made me a little envious that I was stuck out in Orange County with an organization that cut corners. We had a near-championship team and could’ve been on the level of those organizations if only management was more committed.

As much as I loved the guys in the locker room, I found myself fantasizing about going to the 49ers and Washington, two organizations with reputations of taking care of their players. My cousin Dexter Manley was a star with Washington, and we’d compare notes when we’d hang out in Texas in the offseason, and our feelings about our organizations couldn’t have been more different.

All of it — my fear of injury, my feeling of having been ripped off my first two years in the league, the realization that the NFL is a business — was on my mind when I decided to hold out before the 1985 season.

::

I wanted $1.4 million a season — but I was slated to earn $200,000, which wasn’t even in the top 15 among running backs. The Rams didn’t budge. So I went back home to my mom’s house when training camp started. I expected to be back in camp in just a few days, but then a week went by without a new deal, and then two weeks went by.

I wound up staying home for 47 days.

I was back in sleepy Sealy, 50 miles outside of Houston, laying low — it was almost like it was hiding out. I was bored as hell. I’d work out at the high school and at a gym, and rent movies and watch them all day. "A Fistful of Dollars," "Hang ‘em High," "For a Few Dollars More." I binged those Clint Eastwood movies before the term “binge-watch” existed. This was before I’d built my mom her house, so I was in my small childhood house, and it didn’t feel real that I’d met Eastwood the year before in glamorous L.A. Being back in Sealy, I was a long way from that world.

Sometimes I’d take my mom out to dinner; mostly she’d cook. She liked having me home because she was always worried I’d hurt myself playing football anyway.

—I hate that sport, she’d say. I hate that you’re showing them your talent and they’re not appreciating it.

When I did venture out, a lot of people in Sealy gave me a hard time. It was the same people who had always been jealous of me, the type of people who get threatened when someone has the audacity to leave their small world and show how small it really is.

—Why you ain’t at camp! they’d say. You signed a contract!

I got tired of having to explain that in the NFL, that logic doesn’t hold. If I’d have gotten hurt and never played again, the Rams could’ve torn up my contract just like that. Shouldn’t that go both ways?

But people didn’t get it. In the ‘80s, when salaries for athletes started to explode, most fans couldn’t understand how someone making multiple times what they were could possibly complain. They didn’t get that if you were getting paid $200,000 — more money than all but a handful of people in Sealy had ever seen — but producing $1.5 million in value, it’s possible to be grateful for the $200,000 while still feeling like you’re having $1.3 million ripped out of your pocket. I couldn’t explain to them that after two years of breaking records on an unfair deal, you start to become less grateful and more bitter.

While I sat at home, the writers back in L.A. teed off on me. Our relationship had always been tense. I’d been mistrustful of the media since high school and had never been the warm and cuddly superstar they’d wanted. A lot of guys, many who come from rough home lives, seek validation from the media and love from the public, but that was never me. I got plenty of love at home from my mom and dad, so I didn’t come to the media needing anything, and I think that rubbed people the wrong way. When I held out, the writers showed their true feelings about me.

The names they called me sting to this day: Eric the Ingrate. That word: Ingrate. It even sounds like the n-word. It tells me I should be happy I was getting paid at all. It tells me to shut up and run.

They said I was a locker room lawyer. A malcontent. Difficult, petulant — basically any word they could think of as a substitute for uppity. That I was not a team player, because I was all about the money. The audacity I had to be wanting to be paid like a quarterback, which, given the lack of Black quarterbacks, read to me like a coded way of saying that I wanted to get paid like a white player. (On that topic, when was the last time you saw a quarterback hold out?)

The media instinctively takes the side of ownership in disputes with players, and back then it was even worse.

This is true for a couple of reasons: First, players are only with a franchise for a few years — really, we’re just visiting — but ownership and the media are there for the long haul, so their perspective is the same. Second, NFL players are mostly Black, while ownership and the media are basically white institutions. That was even more true back when I played, when the writers in the Rams’ locker room after a game were all white. So yes, I’m saying that racism plays a huge role in how these things are covered, and that was even more the case back then.

Nowadays, we hear a lot of talk about unconscious bias, the way, as my mom would say, It’s just different for us. When it comes to the way the media covered me, I got my first taste of this in high school, with the whole Trans Am thing, where I was made out like some kind of criminal. Then, in college, when I struggled my first year, I was shocked by how viscious the writers were, and how gleeful they were that Craig James — the running back with whom I split the carries for much of his college career — was doing better than me. I was a teenage kid, and there were middle-aged columnists in a major American city arguing that they should take away my scholarship. Even at that age, I realized there was something f— up about that, something dehumanizing. I knew there was no chance any of those columnists would want the same thing written about their teenage sons.

Then my holdout with the Rams. The writers were too savvy to say so explicitly, but they were basically trading on that old stereotype to describe me: The angry Black guy. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy, because after they wrote that s—, I became what they said I was.

To a large degree, that’s been my reputation ever since. It’s complete bulls—. Ask my teammates or anyone who knows me: My parents raised a standup guy and a loyal friend. They raised a guy who played as hard as anyone — and took a lot more punishment than most. Back then and even now, people tell me I’m nothing like how they portrayed me.

All I did was ask for basic fairness, which is something every American should do. But yeah, it’s just different for us, and for that, I was portrayed as a bad guy by a bunch of old white guys (the media) doing the bidding of another bunch of old white people (team management). The things they wrote were so unfair and made me feel so powerless. The best analogy I can think of is that it’s like being convicted of a crime I didn’t commit.

::

That was the writers. The fan mail I got didn’t even bother with the coded language.

—You n— should play for free to entertain us.

—You’re just a bunch of monkeys anyway.

—Why don’t you go back to Africa.

You get letters like that sent to your mom’s house and it hurts, forever. As a Black person, those letters remind you that those people are out there, hiding in plain sight. They’re the people waiting in line for your autograph. They’re the people wearing your number 29 jersey. Those letters are the type of thing you can’t unsee, the type of thing that forms your outlook for the rest of your life. If you’ve ever wondered why I’ve never been a cuddly superstar, why I’m not a Black guy who’s easy for white people to embrace, look no further than those letters.

Or just look at Colin Kaepernick. I knew from the very beginning he’d get run out of the league and never play again. I said as much at the time on TV, on my regular spot as a football pundit on FS1, and here we are all these years later.

His crime? Taking a knee. The most peaceful form of protest imaginable. Something he discussed ahead of time with a veteran to make sure it was respectful to the military.

I can’t see how anyone could possibly disagree with what he was trying to point out. Yes, a lot of great things have been done in the name of that flag, but so have a lot of horrible things. Unjust wars. Stealing land from the Native Americans and committing genocide. Stealing people from Africa and a legacy of white supremacy. Kaepernick was trying to make people stop and reflect. But white America doesn’t like reflecting on things that make them uncomfortable.

Think about what Kaepernick did and how pissed off people were about it. Now think about what those crazy Trump supporters did for their “protest” at the Capitol, and how they were basically allowed to just waltz right in and take selfies with the cops. Can you imagine what would’ve happened if thousands of Black people had rushed the Capitol? They would’ve brought out the military and they’d have been picking up bodies from the steps for weeks afterward. A lot of white people saw what happened at the Capitol and were shocked. Black people weren’t.

That’s what Kaepernick was getting at, and that’s what the NFL didn’t want to hear. When you’re Black in America, all of society’s machinery is stacked against you. In my case, that meant team ownership and the media. For all Black people, that means the police.

My mom drilled that into me when I was growing up: Eric, you can’t trust the police. If they pull you over, it’s ‘Yes sir, no sir.’ The minute you make a wrong move, they’ll shoot you. And when the police report comes out, they’ll have a whole different story.

I have a young son now. In a couple of years, I’ll be telling him the same thing. Black people call it The Talk. Among us, it needs no further explanation.

After that cop murdered George Floyd, the NFL made a big thing about finally getting it and wanting to fight racism. They pledged to donate $250 million over 10 years for antiracism efforts. But that’s chump change to them. They also wrote END RACISM in the end zones, which is a good marketing move but nothing more. Roger Goodell publicly apologized to Kaepernick, but sometimes sorry doesn’t cut it. Because Kaepernick is still out of the league. Because while the league is 70 percent Black, but there are only two Black head coaches and one Black general manager.

The NFL’s messaging may have changed because it had to. But the underlying reality has not.

This article has been adapted from"Watch My Smoke: The Eric Dickerson Story,” by Eric Dickerson, with Greg Hanlon. Copyright © 2022. Available from Haymarket Books. You can purchase the book here.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.