Shadow force: The secret history of the U.S. intelligence community's battle with Iran's Revolutionary Guard

The hackers pretended to be professors, appealing to Achilles’ heel of academics: their egos. Posing as admiring colleagues from other universities, they emailed their targets, claiming they had enjoyed their articles and wanted to read more of their work. The emails contained links to articles the “professors” claimed they could not access.

Once the actual professors clicked on these links, they were redirected to what seemed to be the login page for their universities, making it appear they had somehow inadvertently signed out. But the login page was fake. And once the professors entered their usernames and passwords, the information was captured by the hackers, who then had free rein over their accounts.

This wasn’t the work of run-of-the-mill cybercriminals. In March 2018, federal prosecutors in New York unsealed a shocking indictment: nine Iranians, prosecutors said, working on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), had undertaken a “massive, coordinated” hacking campaign that targeted hundreds of universities across the globe, including 144 based in the United States, as well as private U.S. and European companies, U.S. federal agencies and state governments, and the United Nations.

From at least 2013, these IRGC-sponsored hackers tried to infiltrate about 50,000 academic email accounts in the United States, said prosecutors, and successfully compromised roughly 3,700 of them. The hackers allegedly stole $3.4 billion in intellectual property and academic data from U.S.-based universities alone in “one of the largest state-sponsored hacking campaigns ever prosecuted by the Department of Justice,” said Geoffrey Berman, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, at a press conference announcing the charges.

Many countries have military and intelligence agencies that operate abroad, but few are as far-reaching or prolific as the Revolutionary Guard, which has been involved in everything from conducting espionage campaigns in Europe and the Americas to supporting proxy forces in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

There is “nothing analogous to the IRGC in the West,” said a former senior intelligence official. The Revolutionary Guard has its own army, navy, air force and militia; vast and lucrative business interests; and covert action capabilities — led by its Quds Force — that are a kind of “combination of the CIA and special forces.” But the Revolutionary Guard’s close, symbiotic relationship with Iran’s Supreme Leader is probably its most notable characteristic. “The IRGC’s primary focus is spreading and protecting the revolution,” said the same former senior official.

At the same time, over the past decade, and over two successive presidential administrations, U.S. officials have struggled with how to respond to a unique organization that is simultaneously a conventional military actor, covert action force, intelligence agency, ideological vanguard and sponsor and facilitator of terrorism.

The April decision by the Trump administration to designate the Revolutionary Guard as a foreign terrorist organization — an unprecedented move against an arm of a government — sheds renewed light on a powerful institution that dominates Iran’s security apparatus and is regarded as a formidable regional threat in the Middle East. It also raises the question of whether that designation has merely emboldened the organization, a concern highlighted by the recent sabotage attacks on oil tankers passing through the Gulf of Oman and off the coast of the United Arab Emirates in May.

Trump administration officials blame the Revolutionary Guard for those attacks, though the regime has denied responsibility. But the guard has claimed responsibility for the recent shooting down of a U.S. drone that Iran claims entered its airspace, and for seizing a British-flagged oil tanker in the Persian Gulf on Sunday. (U.S. officials have said the drone was operating over international airspace.)

In fact, the history of the U.S. government’s attempts to deal with the hydra-like IRGC has been one of frustration and setbacks that defy easy solutions. Fifteen former intelligence and national security officials interviewed by Yahoo News describe an organization that can operate aggressively and is willing to resort to acts of terrorism. Those interviews also reveal a variety of previously unreported operations, including details of the IRGC’s involvement in a notorious computer hack, surveillance operations on U.S. soil and even a convoluted U.S. plan to negotiate with Iranian agents to trade aircraft parts for a kidnapped CIA contractor.

While none claim to know the perfect strategy for dealing with the Revolutionary Guard’s aggressive operations, some of those former officials worry that the Trump administration's approach is an extreme one, and may itself catalyze increasing IRGC adventurism abroad — and with it, the risk of confrontation with American forces.

The FBI, CIA and Department of Defense declined to comment. The Iranian Mission to the United Nations also did not respond to requests for comment.

Dealing with the Revolutionary Guard was “complicated,” said Richard Nephew, an Iran director at the National Security Council from 2011 to 2013 who helped lead the Obama administration’s sanctions policy. “We looked at the IRGC as being a regional force that employed tactics that were both conventional and unconventional, including direct support for terrorism,” he said. “Simply to say they are a terrorist group — well, yes, one can say that. At the same time, though, they get a budget line that comes directly from the Iranian budget; they are seen as part of the security system of the country.”

But even if the Obama administration — and, before it, the George W. Bush administration — struggled with finding a way to deal with the IRGC, Nephew is critical of the idea that the Trump White House’s decision to designate it as a terrorist group will meet with any greater success.

“They are not a proxy group,” Nephew said. “You cannot simply say, ‘Cut them off.’”

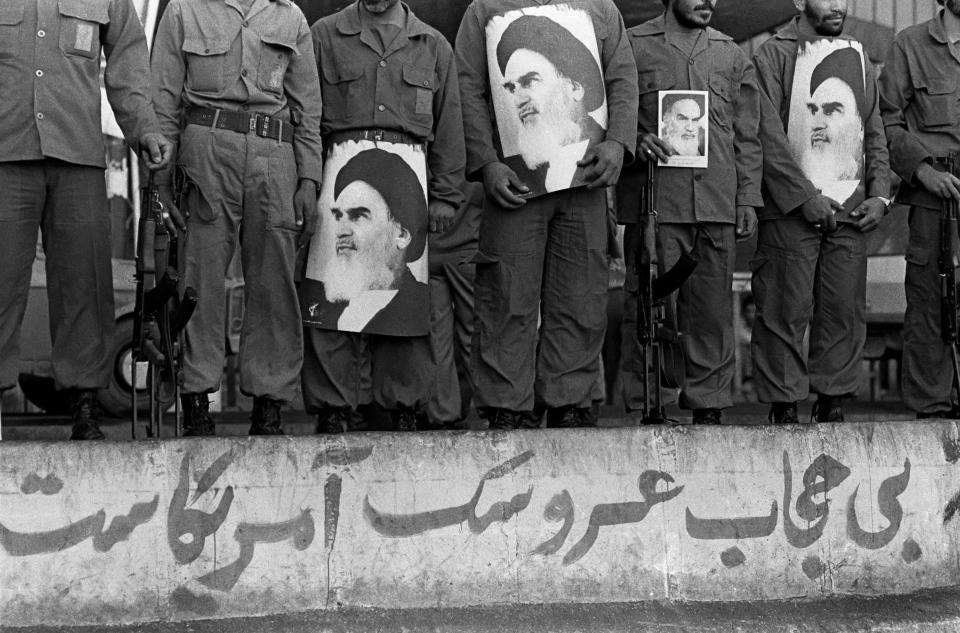

Founded in the aftermath of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, the IRGC was created by the country’s then ruler, Ayatollah Khomeini, to protect and fortify the young regime. With Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran’s oil fields in 1980 — setting off a bloody eight-year conflict that killed more than 1 million — Tehran’s post-revolutionary regime was thrust into almost immediate crisis, with the IRGC taking a lead role in repelling the invading Iraqis.

The IRGC soon became the most formidable player in Iran’s security apparatus, and one of the regime’s key centers of power, operating in parallel to, and eventually dominating, Iran’s regular military forces. But the Revolutionary Guard is much more than just a military actor: Its covert action arm, the Quds Force, quickly fanned out across the wider Middle East, building relationships with Shiite militants and terrorists in the region. Most notably, the Quds Force helped create, equip and train Lebanese Hezbollah, which would bear responsibility for many of the worst acts of terror worldwide in the 1980s and 1990s and is arguably the most sophisticated terrorist organization in existence today.

After more than two decades of hostilities, there was a slight thaw in U.S.-Iran relations after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The immediate threat of al-Qaida — an extremist Sunni organization hostile to both the U.S. and Iran’s overwhelmingly Shiite population — allowed for circumscribed discussions and cooperation between the two countries, said three former U.S. intelligence officials.

In the aftermath of 9/11, al-Qaida fighters — and bin Laden family members — sought refuge in Iran from over the Afghan border. According to “The Exile,” a 2017 book by Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy, Quds Force operatives provided these fighters and family members safe harbor and the freedom to funnel fighters back into Afghanistan and, later, Iraq. Meanwhile, the reformist president Mohammad Khatami sought to arrest or expel these same al-Qaida officials — setting up a high-level clash within the Iranian regime.

During this post-9/11 window, recalled two former intelligence officials, the U.S. used intermediaries to pass information about some of these al-Qaida operators in Iran to the government there. The Iranian regime’s response to the U.S. government’s outreach was mixed, likely a reflection of these competing elements within the regime. Sometimes these al-Qaida figures had their internet use restricted, or were put under house arrest, or were “taken off the battlefield” by Iranian security forces, recalled a former official with experience in the Middle East. Other times, though, the Iranians seemed unable — or unwilling — to intercede. The attitude was to “turn a blind eye,” recalled the former official.

During this time, CIA officials also secretly sent agents and intelligence officers into Iran to hunt for senior al-Qaida operatives there, and — using a combination of signals intelligence and on-the-ground confirmation — successfully located some of them, said the same former senior intelligence official. The agency also “worked closely” with allied foreign intelligence services, which sent their own operatives into Iran to hunt for al-Qaida, said the former senior official.

Around the same time, said two former intelligence officials, U.S. and Iranian officials engaged in secret high-level discussions about al-Qaida. According to the former senior official, who was directly familiar with the negotiations, there were several face-to-face meetings between State Department, CIA, NSC and Defense officials and Iranian government representatives on this issue.

One major point of the negotiations, which continued intermittently after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003, involved the U.S. request that the Iranians hand over al-Qaida figures under house arrest in Iran. Tehran countered that the U.S. should give Iran the leadership of the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq (MEK) — a violent anti-regime group on a U.S. terrorism list from 1997 to 2012 — then living under American authority in Iraq. U.S. officials balked at this request, first reported by NBC News, because the Pentagon wanted to use the MEK for future operations, potentially as the core for an insurgency, recalls this former senior official: “DOD was adamant that the MEK was going to stay intact.”

The Iraq War was another blow to U.S.-Iran relations: Iran was highly suspicious of the U.S. designs in the region. During “rare opportunities to exchange perspective” with senior Iranians, these individuals would tell U.S. officials that the “only reason” the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, and subsequently Iraq, was to encircle Iran, recalled Douglas Wise, a former senior CIA official and deputy director of the Defense Intelligence Agency who retired in 2016.

While leaders in Tehran may have misinterpreted American intentions, U.S. military officials did, in fact, step up contingency planning for war with Iran after the invasion of Iraq, recalled the former senior intelligence official. Using false identification documents, undercover Pentagon special operators flew into Iran using civilian airlines, legally entered the country and secretly gathered intelligence on sites of interest for military targeting, recalled this person. (According to Sean Naylor’s account in his book, Relentless Strike, one mission determined operators could get close enough to Iran’s nuclear sites to take a soil sample.)

The “civilians in DOD” were just “crazed with excitement” after the invasion of Iraq, recalled this person. “They had ‘victory fever’ after we overthrew Saddam. There was literally talk of, ‘Don’t stop in Iraq, keeping sweeping on into Iran.’”

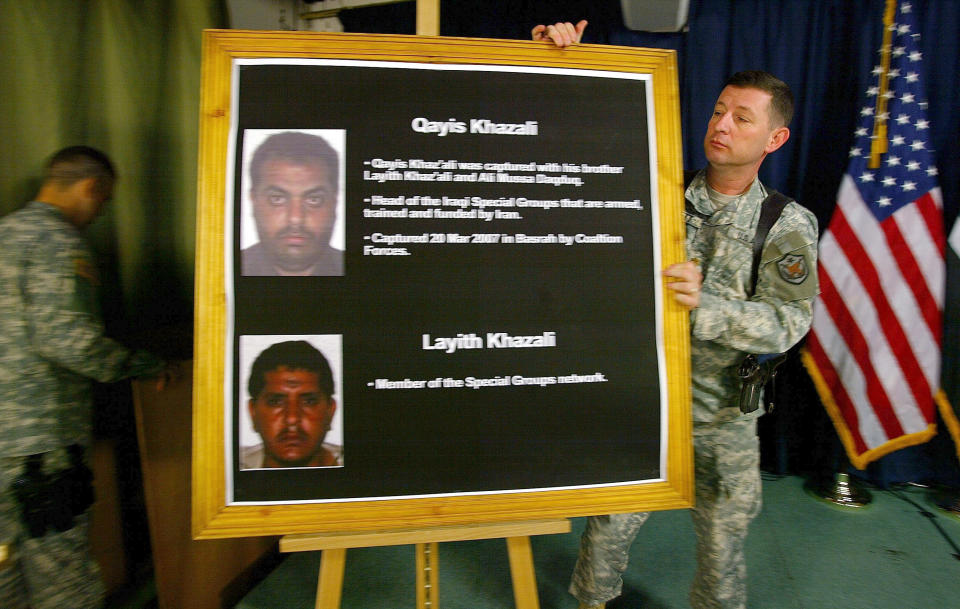

In the meantime, Iran was able to exploit a power vacuum in Iraq left when the United States seemed to lack a coherent transition plan. This involved political influence schemes but also direct support by the IRGC’s Quds Force for Shiite militias, who waged a vicious insurgency against American troops in the postwar years. Some attacks — like the raid on a U.S. military facility in Karbala, Iraq, in 2007 that killed five U.S. troops — appear to have been carried out with explicit support from the Quds Force and its Lebanese Hezbollah proxies.

“We used to say, ‘These guys aren’t getting GPS coordinates for no reason,’” recalled the former intelligence official with experience in the Middle East, recounting Iranian intelligence activity in Iraq dating back to the mid-2000s. “They knew where all the [Joint Special Operations Command] facilities were, where all the al-Qaida interrogation facilities were.”

In what was almost certainly its deadliest contribution to the conflict in Iraq, the Quds Force also provided its proxies there with the know-how and materiel to make explosively formed penetrators, known as EFPs — bombs designed to pierce vehicles and tank armor. “The designs were all IRGC,” said Wise.

In January 2009, the newly in-place Obama administration began calling for negotiations with Iran without preconditions over its nuclear program and support for Shiite militias in Iraq. Yet the Obama administration’s view of the IRGC, and particularly the Quds Force, was soon hardened by two key events, recalled Kelly Magsamen, the Iran director at the National Security Council from 2008 to 2011.

The first was the “Green Revolution” — the massive wave of pro-reform protests after the 2009 Iranian presidential election, and the brutal crackdown that followed, spearheaded by the IRGC. “There was never a sense of naiveté around the challenge the IRGC presented to the United States, but it was a turning point. It hardened a lot of views, and displayed what we were dealing with,” said Magsamen.

The second major issue was the Quds Force’s material support and training for the Shiite militias in Iraq. The Quds Force was “the worst of the worst,” recalled Magsamen. “Really going hard on them was a big focus for us.”

But even as the Obama administration looked for ways to stop the Quds Force in Iraq, the Revolutionary Guard’s operatives continued to ramp up their intelligence activities on American soil. U.S. Intelligence officials describe the Revolutionary Guard as a key player in gathering technical intelligence and facilitating the export of prohibited technology related to Iran’s conventional military forces — as well as, in the past, for Iran’s covert nuclear program.

At the time, Iranian operatives were most interested in obtaining technology related to the country’s nuclear program, including in what another former official called “peripheral, non-obvious” tech — for instance, objects like vibration sensors, which can be used for innocuous purposes, like roadwork, but are also used in nuclear testing.

“The uptick was in the pressure to steal IP,” recalled a former counterintelligence executive. “There was more of an aggressive effort in technology transfer.” Iranian operatives were also keenly focused on obtaining centrifuges, and computer technology related to Iran’s missile program, said this former official.

Iranian operatives would “flood the zone,” recalled a former senior national security official — and would often ship prohibited exports through countries not under U.S. sanctions, and then onto Iran.

The Revolutionary Guard is not the only Iranian spy agency that operates in the U.S., said former U.S. officials. Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) also conducts espionage stateside, said former officials, and sometimes it is difficult for U.S. intelligence officials to pinpoint attribution for specific acts to one organization or the other. MOIS has the reputation for conducting quieter, more traditional intelligence-gathering activities around the globe.

But the Revolutionary Guard and its covert action wing — the Quds Force, led by Gen. Qassem Suleimani — is the dominant player in the Iranian national security apparatus. It’s unanimous that “Quds Force is the real power structure in the country,” said a former U.S. intelligence official who worked on Iran-related targets. “It’s Suleimani reporting directly to [Supreme Leader Ali] Khamenei.”

Washington and Tehran have not had diplomatic relations since 1979, so Iran cannot insert intelligence officers into the United States via “official cover,” that is, placement in embassies or consulates. Instead, the regime relies on travelers, students and others for conducting espionage on U.S. soil. (Iran maintains an official diplomatic presence at its mission to the United Nations in New York City and a small Interests Section housed within the Pakistani Embassy in Washington.)

While goods and know-how connected to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic-weapons program was the top priority for U.S.-based Iranian operatives, the secondary focus is, and was, in obtaining conventional military technology — such as cockpit display systems, night-vision technology and spare parts for its aircraft. “The IRGC is trying to keep the Iranian military apparatus functional,” said the former senior national security official.

Some of the time, Iranian operatives targeted academia to fulfill these objectives. In one case around 2015, said two former senior officials, U.S. officials identified a professor in the Los Angeles area they believed to be a Revolutionary Guard operative. This person, a permanent U.S. resident, had a PhD from an aeronautical school in Iran. U.S. officials believed “this guy had been inserted years and years ago — they had planted the seed,” recalled the former senior national security official.

U.S. officials also believed that a small number of Iranian operatives with advanced degrees in subjects related to aeronautical engineering or nuclear physics, working with the Revolutionary Guard, were then instructed to apply for degrees at L.A.-area institutions — though in unrelated, “safe” fields, like the humanities — while covertly conducting research together to further Iran’s ballistic-missile and nuclear programs, said this person.

Though U.S. officials did confirm a few cases of actual intelligence officers entering the country under the student visa program, Iran relied on co-opted students, and not formal spies, for its intelligence-collection efforts at universities, said the former counterintelligence executive.

Covert online communications between the student-agents and their handlers often traveled through Canadian IP addresses, said the former counterintelligence executive. “We shared all this with the Canadian intelligence services,” recalled this person. “They confirmed they had big problems on their hands.” (Canada suspended diplomatic relations with Iran in 2012.) The Canadian Security Intelligence Service did not respond to a request for comment.

Although Iranian intelligence agencies attempted to insert a limited number of agents into the country via student visas, there were stringent and generally successful measures in place during the George W. Bush and Obama administrations to weed out suspicious applicants without instituting a blanket ban on Iranian passport holders, said Nephew, the Obama-era NSC official.

Concerns about Iranian operatives in the United States peaked with the IRGC’s attempted assassination of the Saudi ambassador in a Washington, D.C., restaurant in late 2011. The botched assassination led U.S. intelligence officials to focus on Iranian travelers conducting intelligence operations domestically, said a former senior counterintelligence official.

The large Iranian-American population in the Los Angeles area — one of the biggest in the world outside Iran itself — made the city a particular target, recalled the former senior national security official. “One of the IRGC’s missions in the U.S. is to infiltrate the diaspora and find past and present enemies of the Iranian regime,” said this person. “We would hear about stuff like that all the time from informants or cooperating individuals in the Persian community.” (In one case, in 2018, federal prosecutors charged Majid Ghorbani, a longtime U.S. permanent resident in Orange County, Calif., of working as an Iranian intelligence agent gathering information about MEK members in the United States.)

Iranian intelligence is also acutely focused on tracking down defectors — including former Iranian intelligence officials — living in California and elsewhere, said another former U.S. intelligence official. “They are very specifically looking for a named list of individuals that they know are here,” said a former intelligence official.

And they are willing to invest significant resources to procure this information: The ultimate objective of a hack of the accounting firm Deloitte around 2016, which was carried out by the Iranian government, said this same former intelligence official, was to track down a U.S.-based former IRGC official connected to the firm. A second former official confirmed that the hack was designed to target an Iranian defector. (Deloitte did not respond to requests for comment.)

Some U.S. intelligence officials believed that the Iranians may have been assembling assassination plans for these defectors, said the first former intelligence official who confirmed the purpose of the hack. “They haven’t crossed the line in the U.S. to killing, but they have skirted that line,” said this person. (Other former officials are more skeptical that imminent violence was the intention of these activities but confirm that suspected Iranian intelligence operatives have surveilled defectors on U.S. soil.)

Of course, the FBI has also sought to leverage the Iranian community in California for critical information, said former senior officials. For instance, two former officials described a case during the second term of the Obama administration when the FBI entered into discussions with an Iranian asset based in Los Angeles who claimed to serve as a backchannel to the regime regarding information about Robert Levinson, a former FBI agent. Some believe Levinson, who disappeared in Iran in 2007 while working secretly as a CIA contractor and whose fate is unknown, may have been held at a Revolutionary Guard-controlled prison in Iran.

Discussion between the bureau and the Iranian go-between centered on a secret trade: The Iranian government would provide information about Levinson in exchange for a list of specific commercial plane parts provided by the Iranians, which sanctions against the regime made difficult to procure, said these former officials. This proposal went up, via a memo, to the director level at the FBI — with high-level officials at DOJ, Commerce, Treasury and State all involved, recalled one of those two former intelligence officials.

“This would not have been an Iran-contra thing,” said the former senior counterintelligence official. “The intelligence community would not have gone fully through with the deal, especially if there were no signs of life from Levinson.”

But the potential deal fell apart over fears about the possible military uses of the requested parts, and doubts that the Iranians would fulfill their part of the bargain, recalled these officials. The bureau also got pushback from the CIA about this potential deal, recalled the first former official aware of the potential secret trade, because of concerns about the Iranian source.

U.S. officials concluded that the backchannel was “concocted” by the Iranians, said these two former officials — the second of whom recalled “major issues” with the source, who may have even been a double agent. The Iranians were trying to “play” the bureau, said this person, in a gambit for cash and plane parts. The negotiations, in the end, were dropped.

In September 2013, President Obama initiated a brief phone call to Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s newly elected president — the highest-level contact between a U.S. and Iranian official since 1979 — as part of a frenzied period of diplomacy that would eventually lead to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the landmark Iran deal. But, if anything, the IRGC only intensified its activities abroad during this period, note former U.S. officials.

The Quds Force “was making deliberate efforts to establish zones of influence” in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America, recalled a former senior CIA official. In some areas, these actions included arms smuggling to Iranian proxies and other criminal activities; in other regions — especially in the Middle East — the Quds Force began to provide more overt support to its proxies. “They were trying to really stir the pot,” recalled the same former official. “They saw in instability an opportunity to expand their influence.”

For instance, the Quds Force commander responsible for the proliferation of EFPs in southern Iraq was sent to Yemen around 2013, recalled one former intelligence analyst — and helped Iran’s Houthi allies develop and produce copper EFPs there. “This was sophisticated milling equipment,” recalled this person. “It was not a capacity that Houthis had on their own.”

As Washington and Tehran moved forward with negotiating a nuclear deal, Iranian intelligence operations continued to evolve, pursuing aggressive operations against U.S. targets, and even turned to foreign partners for help. Around 2013, CIA personnel also began to notice improvements in other Iranian intelligence efforts, including in online targeting and strategic messaging, and counterintelligence — leading to discussions within the CIA about what was driving these changes on the Iranian side. “They got better, and they got better quick,” said the former intelligence official with experience in the Middle East.

CIA officials did not reach a definitive conclusion about what was driving these improvements. They believed it was partially the product of a natural maturation on the Iranians’ part — that the IRGC and other services were receiving greater infrastructure and support and had created more sophisticated, dedicated targeting programs — and also because of enhanced cooperation between Iranian intelligence and its Chinese and Russian counterparts.

The successful efforts by the United States and its allies to penetrate and forestall Iran’s nuclear-weapons program — including via the Stuxnet computer worm in 2010 — led Iran to seek outside assistance, said the former senior CIA official. The Iranians realized that “if they didn’t get any eventual help about what was going on, they were going to keep being knocked down the hill [with their nuclear program],” recalled the former senior CIA official.

Some of Iran’s counterintelligence improvements may also have been the result of information provided to the Iranians by Monica Witt, an Air Force counterintelligence officer who defected to Iran in 2013. Witt was involved with a sensitive double-agent program run through the Department of Defense, a fact first reported by the New York Times and confirmed to Yahoo News by two former officials. “She betrayed the people who were working with her,” said one of these officials, who was familiar with the increasing improvements in Iranian intelligence activities. Witt’s disclosures also included true names of Americans working on sensitive Iran targeting matters, said this person.

Iran also began ramping up its online strategic messaging and disinformation operations, becoming more active on platforms like Facebook and Twitter, in an effort to sway public opinion in a pro-Iran direction, recalled two former U.S. officials. There was evidence — including “raw data that suggested cooperation,” said the former senior counterintelligence official — that Russia, China and Iran were sharing information on improving social media practices and online influence schemes around this time. (Earlier this year, Facebook announced it had taken down over 800 “Pages, Groups and Accounts” — which had over 2 million followers — linked to Iran. Twitter has also suspended thousands of accounts it says are linked to an Iranian influence campaign.)

But the most consequential aspect of this increasing cooperation between China, Russia and Iran was in counterintelligence, recalled three former officials. This enhanced information-sharing arrangement, which U.S. officials believe began to take shape around 2010, likely helped catalyze the catastrophic communications compromise that led to the death of dozens of CIA sources in Iran and China.

Even as Iran ramped up its intelligence operations in some areas, the Obama administration moved forward with nuclear negotiations with Tehran, and in July 2015 the United States, Iran and other world powers signed the nuclear accord, a signature achievement of the Obama administration. The resulting easing of sanctions brought about a downward shift in some of the Revolutionary Guard’s activities, particularly in cyber espionage and IP theft, said former officials. (The U.S. had already scaled back some of its own efforts, including operations to “lure” some Iranian agents involved in proliferation to third countries, where they could then be transferred to U.S. custody, said the former senior national security official.)

But spying between the U.S. and Iran, of course, did not cease after the signing of the deal. “The most sensitive stuff going on before continued to go on after,” recalled the former official concerned about improvements in Iranian intelligence activities. “The CIA didn’t get less aggressive” after the Iran deal, said this person. “And no one expected they would be.”

Donald Trump was elected in November 2016 on the heels of a political campaign that focused on blasting the nuclear accord, which he called “the worst deal ever,” and calling for a ban on immigration from Muslim-majority countries. Once in office, he quickly fulfilled his promise on the second matter, issuing a ban on seven countries, including Iran.

In May 2018, Trump followed up on his other major promise by pulling out of the multilateral nuclear accord, announcing that “the United States no longer makes empty threats.” That was followed less than a year later with designating the IRGC as a foreign terrorist organization, a decision that riled some parts of the U.S. national-security community.

The designation worries some former intelligence officials, who believe it may open the CIA and U.S. Special Forces personnel abroad to Iranian targeting. Senior U.S. officials had multiple discussions about naming the Revolutionary Guard a foreign terrorist organization during the Obama administration, but declined to pursue the designation, according to Nephew, who recalled opposition from the Pentagon and CIA. U.S. officials were also concerned that the move could change the military’s “hunting license” under the 2001 authorization for the use of military force, which has provided legal justification for the war on terror, said Nephew.

On a more pragmatic level, said the former intelligence officer who worked on Iran-related targets, designating the entire Revolutionary Guard could have a “serious effect” on the CIA’s ability to gather intelligence on it. “If they can’t travel and, say, go to Europe, it makes it harder as operations officers to develop or recruit them,” said this person. “It’s a ham-fisted approach.” (During the Obama administration, opposition by U.S. intelligence agencies to naming the entire IRGC a foreign terrorist organization rested partially on these concerns, said a former State Department official.)

As tensions between the United States and Iran escalate, it’s unclear what Tehran’s ultimate objective is. The current instability is compounded by long-standing, deep pathologies in the U.S.-Iran relationship, said Wise, the former senior CIA official. The Iranians have “an unparalleled paranoia,” said Wise, who worries about Iranian security officials who see "saber rattling” and misinterpret it “as the onset of an attack on Persia. And then they act in the only way they can, and we’d have no choice but to unleash on Iran.”

In the end, the issues in U.S.-Iran relations are larger than the Revolutionary Guard itself, said Nephew, the former NSC official. “What we need is for the Supreme Leader of Iran to believe it is not in his country’s best interests” to continue certain policies, said Nephew. “Iran’s support for the Houthis and Bashar al-Assad, the decision to arm Shia militants to attack U.S. forces — these are decisions being made at the state level. They were not things that Qassem Suleimani woke up one day and said, ‘Let’s do this.’”

But the immediate issue now is that the terrorist designation and subsequent sanctions risk the Iranians’ reacting in ways the United States didn’t expect. Rather than push Iran to new negotiations, as Trump seems to hope, the Iranian reaction risks a critical escalation in the region.

“The challenge is that the Iranians truly perceive at this stage that this is full-on economic war. Here in Washington, it doesn’t cost the treasury secretary anything to go to the podium and announce 25 new designations,” said Magsamen. “But the Iranians, their perception of it is very different than ours. In their minds, they are justified in sending a signal on the tankers, that they can hit back. We think that’s a crazy, disproportional reaction — that’s not how they think about it.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: