Sanders follows a path to the nomination blazed by ... Donald Trump

Welcome to 2020 Vision, the Yahoo News column covering the presidential race with one key takeaway every weekday and a wrap-up each weekend. Reminder: There are 5 days until the Iowa caucuses and 279 days until the 2020 election.

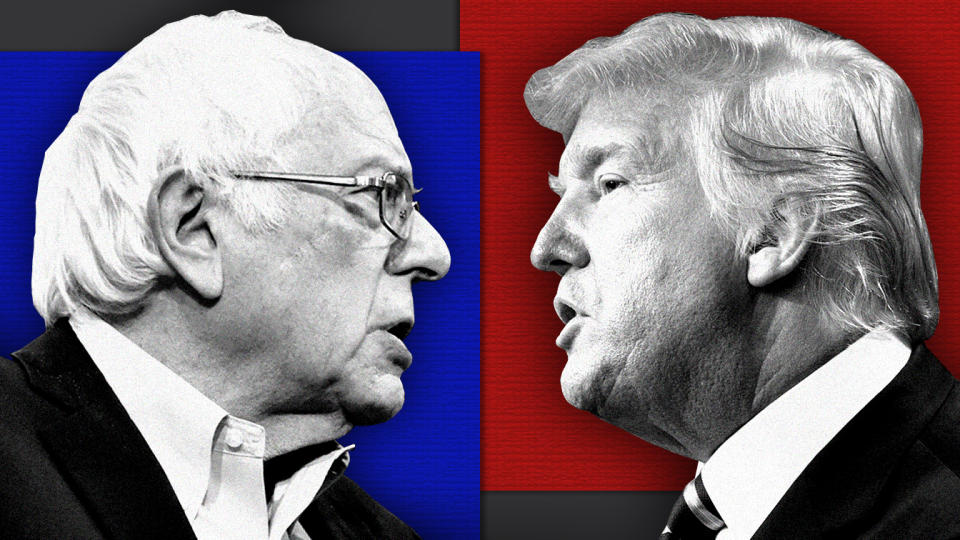

Their massive rallies. Their passionate followings. Their populist, anti-establishment brands. Their brusque personalities. Their New York City roots. Even their age (70s), race (white) and gender (male).

Plenty of ink, digital and actual, has been spilled over the parallels between Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. It was a major theme of the 2016 presidential campaign and the postmortems that followed.

The truth is, their differences are just as pronounced as their similarities, and far more substantive. Trump had zero political experience before running for president. Sanders first ran for office in 1972 and has been serving the public in one capacity or another — mayor, congressman, senator — for the last four decades. Trump has no ideology. Sanders has been championing the same progressive policies since the start of his career: single-payer health care, anti-interventionism, fair trade. Trump has made 16,241 false or misleading claims as president. Voters consider Sanders the most honest of the 2020 candidates.

Yet as the Iowa caucuses approach, and as Sanders gains ground in poll after poll after poll, there is one comparison with the president that may come to matter more than the contrasts: the fact that Bernie’s path to the nomination is beginning to resemble Trump’s in 2016.

It’s hard to remember now, but four years ago Trump won the lowest percentage of the primary vote — 44.9 percent — of any Republican presidential nominee since Richard Nixon in 1968. The only other modern GOP nominee who failed to secure a majority, John McCain, won nearly 47 percent of the primary vote in 2008. And McCain encountered none of the mainstream GOP resistance that Trump did. Millions more Republicans voted against Trump than any of the party’s previous nominees. Establishment figures were still trying to block his nomination during the Republican National Convention. Trump’s main rival, Ted Cruz, pointedly refused to endorse him while addressing the delegates and even encouraged rank-and-file Republicans to vote for someone else.

The reason Trump wound up winning was that he faced a huge field of 16 rivals, including several big-name Republicans who split the anti-Trump vote: Cruz, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, John Kasich. Their continued presence in the race — and the lack of any mechanism that could winnow all but one of them out — prevented mainstream Republicans from consolidating behind a single alternative to Trump until it was too late for him to be stopped.

Sound familiar?

Right now, Sanders is leading in Iowa with an average of 24.2 percent of the vote. He is leading in New Hampshire with an average of 24 percent of the vote. He is polling at 17 or 18 percent in Nevada, hot on Joe Biden’s heels. And he is leading in California with an average of 24.3 percent of the vote.

If those numbers hold, Sanders could wind up winning three of the first four states and the most delegates on Super Tuesday, which would put him well on his way to securing the nomination. But if Sanders does, in fact, win key early states with only a quarter of the vote, it would mean something else as well: that three-quarters of early-state Democrats did not support his candidacy.

Even Trump performed better than that. After losing to Cruz in Iowa with 24.3 percent of the vote, Trump cleared 35 percent in New Hampshire. From then on, he basically never fell below 30 percent again, scoring decisive victories in South Carolina, Nevada and seven Super Tuesday states. By March, he was the presumptive nominee.

It’s entirely possible that Sanders could prevail in this year’s primary with even less overall support than Trump. The day of the 2016 Iowa caucuses, Trump was polling nationally at 35.8 percent, on average; Cruz was at 20.3 percent; Rubio was at 10 percent. No one else was in double digits. Today, Sanders is polling nationally at about (you guessed it) 24 percent, on average; Biden is actually ahead of him at 28 percent, and five other candidates — Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg, Mike Bloomberg, Tom Steyer and Amy Klobuchar — have recently crossed the double-digit mark in two or more national or early-state surveys.

What’s more, the GOP allocates at least some of its delegates in a winner-take-all fashion; the Democratic primary is entirely proportional, meaning that anyone who clears 15 percent in a particular state will get at least some delegates. That, in turn, increases the chances of an extended primary process and a nominee with a minority of the vote. In short, the relative strength of Sanders’s rivals creates the same sort of collective action problem that produced Trump — only worse. That’s why Buttigieg is the only candidate who’s even questioning Sanders’s electability at this point, and why Klobuchar aides just rebuffed an overture from the Biden camp to form an alliance in Iowa.

The potential impact of a divided anti-Bernie opposition is clear when pollsters ask primary voters about hypothetical head-to-head matchups between the leading Democratic contenders. Eliminate the rest of the field and put Sanders in a one-on-one contest with Biden, for instance, and the former vice president clobbers the Vermont senator: 54 to 38 percent in a new Echelon Insights survey and 53 to 41 percent in a new YouGov Blue/Data for Progress poll. Substitute Warren for Sanders, however, and she attracts much broader support: Echelon found her trailing Biden by 5 points, while YouGov had her behind by 2. Warren even led Sanders by 7 points in a three-way fight with the former veep. Yet unless everyone else drops out, Sanders could defeat both of them.

This might have major implications in November. The Sanders campaign promises that their man will lure new, nontraditional voters to the polls, much as Barack Obama did in 2008. Given Sanders’s non-mainstream appeal and the unrivaled enthusiasm he engenders among his supporters, that’s not implausible.

But will it be enough? In 2016, Trump went from losing a majority of the Republican primary vote to losing the popular vote in the general election. The only thing that elevated him to the presidency was the GOP’s huge structural advantage in the Electoral College.

Democrats are in the opposite situation, so Sanders would start at a disadvantage. To beat Trump, he would need more than nonvoters. Like Obama, who assembled a diverse coalition of moderates, progressives, blue-collar whites and voters of color, he would need every Democratic vote he could get. When asked in a November HarrisX survey, however, if they would “ever vote for a Democratic Socialist” — which is how Sanders characterizes his brand of progressivism — 52 percent of Americans said no. That number included 25 percent of Democrats and 29 percent of voters who “lean liberal.” Meanwhile, in a September Civiqs survey, 38 percent of Democratic primary voters who called themselves moderate or conservative expressed an unfavorable opinion of democratic socialism. As Slate’s William Saletan recently put it, “Subtract those people from Democratic turnout, and you’re in trouble.”

At the moment, there’s no reason to assume that anti-Bernie Democrats will stay home if he’s the nominee; he remains the party’s best-liked candidate, and anti-Trump sentiment alone may ensure a united Democratic front on Election Day. There’s also no reason to assume that Sanders will remain at 24 percent in the polls; if his fellow progressive Warren drops out, he will likely rise.

But as Trump demonstrated in 2016, securing your party’s nomination as a plurality candidate creates real complications — both in the primary and the general election. And for now, at least, Sanders’s path looks even more complicated than Trump’s.

Read more from Yahoo News: