Sacheen Littlefeather apology is a reminder that Native Americans are still 'left out' in Hollywood

In August, Native American actress Sacheen Littlefeather received an in-person apology from the Academy Awards for her hostile treatment at the 1973 ceremony, where she was booed while declining the best actor Oscar on behalf of winner Marlon Brando.

"I am here accepting this apology," Littlefeather told the crowd honoring her at "An Evening with Sacheen Littlefeather," an event at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles in September. "Not only for me alone, but as acknowledgment, knowing that it was not only for me but for all of our nations that also need to hear and deserve this apology tonight."

Weeks later, Littlefeather, who was Apache and Yaqui, died at 75. Her family confirmed in a statement to USA TODAY that she died Oct. 2 "peacefully at home" in Marin County, California, "surrounded by loved ones."

But as Hollywood still struggles to make meaningful strides for Indigenous representation in TV and film, some members of the Native American community believe a public apology is the bare minimum.

"Honestly, it's been 50 years since it happened. (It) definitely feels too little too late," says Eric Buffalohead, chair of the American Indian, First Nations and Indigenous Studies department at Augsburg University in Minneapolis.

Sacheen Littlefeather death:Native American activist who declined Marlon Brando's Oscar, dies at 75

'Never thought I'd live to see the day': Oscars apologize to Sacheen Littlefeather for mocked speech

While the apology was an important step, "it's the action of the Academy following this that matters most," says Ian Skorodin, director of strategy of the Native American Media Alliance. "Is the Academy working with Native American community organizations that have a history of elevating native people in media and the arts? How are they supporting these organizations, and what strategies are they building to increase our community membership in the Academy?"

In the wake of #OscarsSoWhite, there have been concerted efforts by Hollywood to promote diversity. This year, the Academy introduced the Indigenous Alliance, which aims to facilitate more opportunities for Indigenous representation in the Academy and throughout the global film community. The Academy has also invited thousands of new people to its voting body since 2016, with 19% of total membership belonging to underrepresented racial or ethnic communities.

Major studios have similarly started programs to foster underrepresented voices, although Native talent still trails far behind other groups in on- and off-screen representation.

According to the latest Hollywood Diversity Report published by the University of California, Los Angeles, Native actors made up just 0.4% of film leads in 2021 – compared to 61.1% white, 15.5% Black, 7.1% Latino and 5.6% Asian. The numbers were similarly dismal behind the camera, with Native people comprising only 0.8% of the directors and writers of the top theatrical and major streaming releases in 2021.

'Prey': Amber Midthunder talks axe throwing, outwitting the Predator and representation

"We been left out of the conversations and still are seen by many as 'something else,' " says Joely Proudfit, department chair of American Indian studies and director of the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center at California State University, San Marcos. "Hollywood executives never consider Native people unless they are told to do so. Otherwise, they have the luxury to not care about being connected to our own mutual history. The scarcity mentality focuses on limitations instead of opportunities.

"It is time for Hollywood to fully invest in opportunities that include a diversity of Native American stories, ranging from a variety of tribal perspectives and genres."

Even when Indigenous people are represented on screen, their stories are often undervalued or ignored by studio heads and awards bodies. Sierra Teller Ornelas, a member of the Navajo Nation, co-created Peacock comedy "Rutherford Falls," which starred Native actors and centered on a fictional town grappling with its colonialist history. But despite strong reviews, the show was canceled earlier this month after two seasons.

For the first time in 233 years: Native American, Native Alaskan, Native Hawaiian all in U.S. House

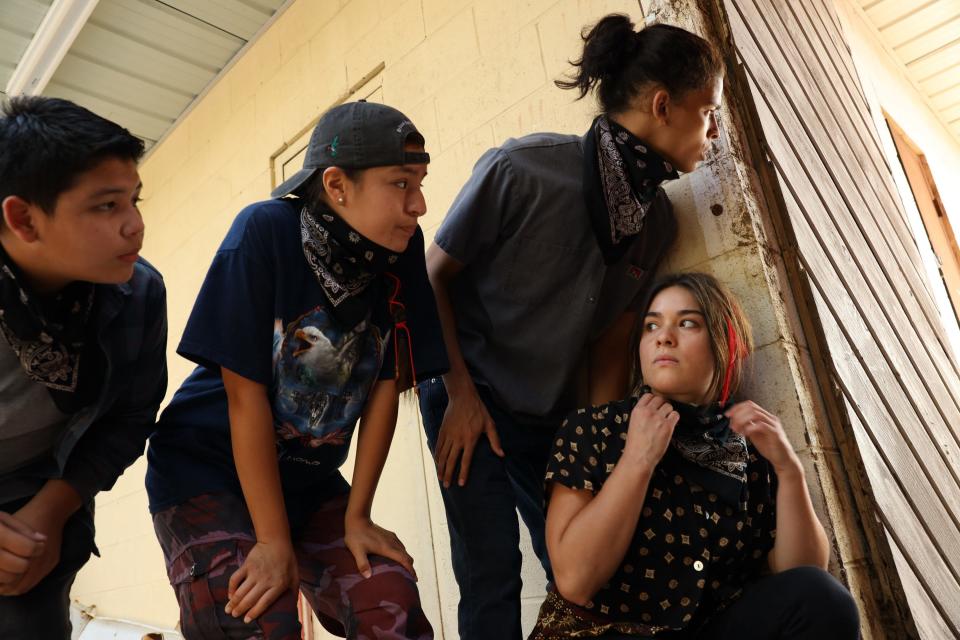

FX/Hulu dramedy "Reservation Dogs," about four Indigenous teenagers in present-day Oklahoma, was similarly well received and was just renewed for a third season. It earned numerous accolades, including a Peabody Award, but was snubbed by the Emmy nominations this year.

Buffalohead believes that Hollywood doesn't see contemporary images of Indigenous people as profitable, given that American Indians and Alaska Natives make up roughly 1.3% of the U.S. population. That's compared to 18.9% of the population that is Hispanic or Latino, 13.6% that is Black, 6.1% that's Asian, and 0.3% that is Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

"Hollywood has spent over 100 years portraying American Indians as a part of the past, stuck forever in 18th- and 19th-century settings," Buffalohead says. "I don't believe the industry sees making entertainment for (that portion) of the American population as a good use of its resources. The fantasy of American Indians has replaced the reality of American Indians in people's minds, and since the American educational system doesn't do justice to teaching about us, those Hollywood images tend to dominate."

As a result, many Native actors may be discouraged from pursuing a career in entertainment, given that "Hollywood-type roles" are frequently "insulting, demeaning and damaging," Buffalohead says.

'I feel very proud': Nicole Mann to become first Native American woman in space

Hulu movie "Prey" and AMC series "Dark Winds" have been praised this year for their authentic Indigenous representation. But other recent projects including ABC's "Alaska Daily" and Taylor Sheridan's "Wind River," and Martin Scorsese's upcoming "Killers of the Flower Moon" have drawn criticism online for centering white characters in stories about violence against Native characters.

"While it’s crucial to highlight our missing and murdered Indigenous women, that should not be our only representation on screen," says Karissa Valencia, creator of Netflix's animated "Spirit Rangers." "We’re more than survivors of violence and genocide. We’re also thriving and have a future."

"Spirit Rangers" has an all-Native writers' room and follows three siblings who transform into animal spirits to help protect the national park they call home. The show was inspired by tribal stories Valencia heard as a kid, growing up as a member of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. With this show, she wanted to capture how all tribes are unique, as well as transcend the Native American caricatures she saw in media growing up, such as Tiger Lily in "Peter Pan."

"To change the types of shows, we need to start behind the scenes," Valencia says. "We desperately need more Indigenous showrunners and directors to be hired. There isn’t one way to 'be Native.' All of our stories are so different. And to really create change, we also need more Indigenous creative executives as well. Executives have the power to say yes to a show that can create change."

'A place for us': Why Ariana DeBose's Oscar win is a major victory for LGBTQ community

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Sacheen Littlefeather got apology. What about other Indigenous people?