On The Road, Again

UPDATE: Poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti died earlier this week, on Feb 22, at the age of 101. He had outlived every member of the generation he helped make famous, the Beats. Ferlinghetti himself never considered himself a Beat, the iconoclastic loosely organized group of friends who rewrote poetry in the 1950s and then were copied by everyone with a typewriter in the ‘60s and beyond. Ferlinghetti was older than them and became a sort of default father figure, confessor and publisher to them all, including the group’s most famous author, Jack Kerouac. It was 2007, the 50th anniversary of Kerouac’s On The Road that inspired this story. I wanted to retrace one of the cross country drives the boys took in that greatest American novel, and after Cadillac loaned me a DeVille I did. I could imagine Kerouac himself sleeping it off in every small town I visited, or shivering in the freezing cold trying to hitchhike west to see his pals. Read on, McDuff, and plan your own road trip for when this is all over and we’re free again.

Man, if my memory could only serve me right the way my mind works I could tell you every detail of the things we did. Ah, but we know time. Everything takes care of itself. I could close my eyes and this old car would take care of itself.

Jack Kerouac's On the Road is surely one of the great road books of all time. There are others, of course, and plenty of other road trips. You could argue that the first great American road trip was Lewis and Clark's. Just picture them, sitting around with Thomas Jefferson, complaining about one thing or another, then the idea strikes them all at the same time and in unison they yell, "ROAD TRIP!" Jefferson later weasels out, saying he has to run the country, "and stuff," but Clark and Lewis go.

Huck Finn went, too, and so did the Joads, Otter and Boone, and a host of others. To get out on the road and revel—to just go—is part of the American psyche. And we have more than enough room to do it in. Sure, Siberia has room, too, but Siberia never had Eisenhower's Interstate Highway System, big V8 engines, and cheap gas (relatively cheap, anyhow).

On the Road was published in 1957 and literary critics at the time said it defined a generation. Almost until the day he died in 1969, Kerouac found himself the reluctant spokesman for that generation, the Beats. But no one wanted to hear about Kerouac's vision of literature, or his religious philosophizing, or anything spiritual or visionary at all. They wanted to hear about the wild parties and days-long cross-country banzai runs described in the book and, more often, the debauchery.

Debauchery sounded good to us.

So the idea was this: Follow the route of the main characters from On the Road, Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, ambling where they ambled, high-tailing it where they high-tailed it, all the time practicing the Beat mantra of, "Go, man, go." It was as good a plan as any. The idea of a road trip, a pure unadulterated road trip, is that there is never much of a plan. The idea is just to go. Man. Go. There are no good reasons that you can explain to a wife, girlfriend, or editor. In the book, Dean once tried to explain an imminent trip to his wife, Camille.

"But what is the purpose of all this? Why are you doing this to me?"

"It's nothing, it's nothing, darling, ah—hem—Sal has pleaded and begged with me to come and get him, it is absolutely necessary...I'll tell you why. No, listen, I'll tell you why." And he told her why, and of course it made no sense.

Not to Camille. But it made perfect sense to Dean and Sal and by golly, it made sense to us.

For Dean Moriarty we thought of Autoweek photographer Bill Delaney. Delaney's far more responsible than Dean Moriarty, of course, but carries some of Dean's philosophical outlook We called him.

"Yeah, man, I really dig those Beat dudes."

Delaney actually talks like that. He could go about halfway, as far as Salt Lake City, where various responsibilities would call him back.

Next, we needed wheels. Dean and Sal crossed the country four times in On the Road, sometimes by bus, sometimes by rail, and most often by car. It was one of the car jaunts we planned to emulate, specifically the leg from San Francisco to Detroit. (Why that leg? I'd tell you why, but of course it would make no sense.) In the book, the trip started in a Plymouth, but that car did not get good reviews from the boys. And besides, Plymouth was almost out of existence by the spring of 2000. The car Dean and Sal got in Denver, that was different.

At the travel bureau there was a tremendous offer for someone to drive a '47 Cadillac limousine to Chicago.

And Cadillac was still around. We called. There were no limos, but there was a DeVille, the next-best thing. "We'll make it happen," said the Cadillac guy, and he did. The next day we loaded the DeVille with water bottles, a small supply of taquitos, and enough 35 mm film to shoot a short documentary and set out, the mad Delaney at the wheel.

"Whooee!" yelled Dean . "Here we go!" And he hunched over the wheel and gunned her; he was back in his element, everybody could see that. We were all delighted, we all realized we were leaving confusion and nonsense behind and performing our one and noble function of the time, move. And we moved!

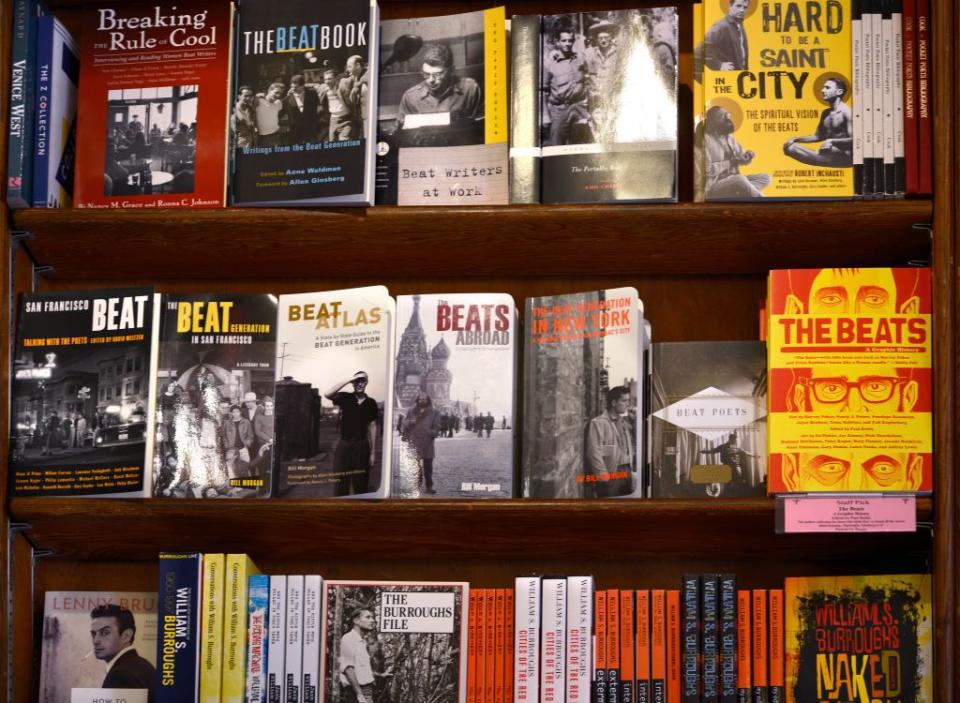

Delaney had a library full of Beat books, everything from Kerouac's The Dharma Bums to Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl." We brought as many as we could carry from his house. Then, to set the proper tone, we agreed we would punctuate our conversation with terms like "daddy-o," "dig that gone cat," and whatever else sounded good.

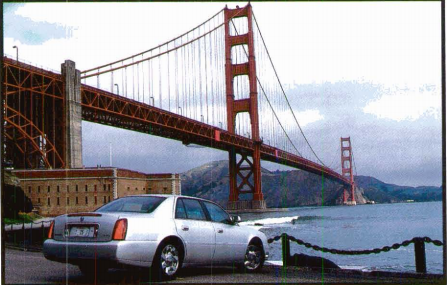

The formalities out of the way, we gunned it up Highway 101 to San Francisco.

"Let's lay some miles down," Delaney said.

And we did, 409 that evening alone, from Ventura to San Francisco in five hours, including a stop in Pismo to drive on the beach.

"Who are the Beats, what is Beat?" Delaney asked, philosophizing and driving at the same time. "Okay, the evolution of automotive transport was completed in 1950, okay? No, delete that. Okay, what you wanna say is as far as getting in a car and going, it was a great time to drive. There you go, that's your line, man. The freedom of the road, the freedom of the mind, you know? And against the, what do you call it, the contentment of the '50s. They didn't want contentment. They wanted to go, man, go.”

We had a CD of Beat and pre-Beat poet William S. Burroughs and played it as we sped through Santa Barbara, but Burroughs was scary. He didn’t seem like a happy guy. So we ejected it and played jazz instead.

In no time we were in San Francisco. Delaney knew exactly where to go first—City Lights bookstore. Not only was it an old hangout of various Beat poets, but it was open till midnight.

On the walls were large black-and-white photos of Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso, Bob Dylan, and a whole bunch of others not immediately recognizable. Upstairs in the back was a single shelf of books devoted to the Beats. We found On the Road and picked it up like pilgrims holding the Grail.

We went down the street to a bar called Enrico's because a guy in City Lights told us Enrico's had jazz and we figured Jazz was Beat, too, Daddy-o.

"There were only four real Beats." said Ward Dunham, who was tending bar at Enrico's while a three-piece jazz group played. "Everybody else was just copying them."

We were copying them, too, we said. We're headed to Denver, Chicago, and Detroit, just like Sal and Dean.

"Denver? Detroit?" Ward said. "You're not going to find anything in Denver and Detroit. It’s all here. Right here."

Ward was organizing the North Beach Bohemian Festival, scheduled the following Sunday, five days away. He said there would be Beats aplenty and that we should stay. We wrestled with this suggestion, then went to another famous Beat hangout, across the alley from City Lights. Café Vesuvio, then to Sam's (definitely not a Beat hangout) for hamburgers at 2 a.m.

Finally, we decided we had to go, man, go.

After a few hours sleep in a motel on Lombard Street ($49, the sign said, and $157 the receipt said), we looked around for old Kerouacian haunts, but everywhere we turned had been "croissanted-out, all stuffed with dot coms," said Delaney, so we headed east.

I hated to leave; my stay had lasted sixty-odd hours. With frantic Dean I was rushing through the world without a chance to see it. In the afternoon we were buzzing toward Sacramento and eastward again.

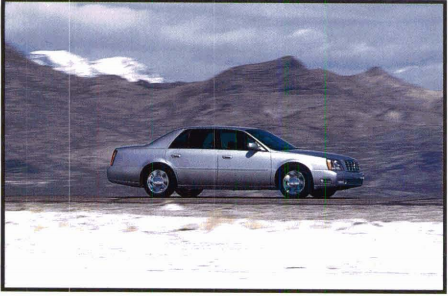

The Sacramento Valley, the Sierras, most of Nevada all flew by with Delaney at the wheel. We approached the Utah state line, at what had to be the same point Sal and Dean did it 50 years before.

Reno, Battle Mountain, Elko, all the towns along the Nevada road shot by one after another, and at dusk we were in the Salt Lake flats with the lights of Salt Lake City infinitesimally glimmering almost a hundred miles across the mirage of the flats, twice showing, above and below the curve of the earth, one, clear, one dim.

We stopped on the edge of the Bonneville Salt Flats, in Wendover, Utah, and stayed in the Bonneville Motel just because it was the same place Craig Breedlove had stayed in 1964. There were classic '50s cars parked all around it, including a couple of '59 Fairlanes with retractable hardtops. The owner had died three weeks before and his son came back from a career as a stuntman to tend the place.

"Craig stayed right over there in room 49," said Cody Lewis. "I don't know what I'm going to do with all these cars."

The next morning, eating breakfast in Wendover, we met two truckers a couple tables over.

"Between us we got over six million miles," said Karl Jorgenson.

"You're gone from home a lot, that's one thing. Course. that's the secret to a long marriage."

"Just be sure you're home for payday," said his friend Larry Woods. "Course, then you can't stick around too long…”

We didn't. The salt flats reeled by and soon we were at the airport and Delaney was pulling his bags out of the trunk and walking into the terminal.

Dean walked off into the long, red dusk. His shadow followed him, it aped his walk and thoughts and very being… Suddenly he bent to his life and walked quickly out of sight. I gaped into the bleakness of my own days. I had a long way to go, too.

First was Colorado, slipping over the Rockies at Berthoud Pass, 11,315 feet up and it looked like winter wasn't quite done with that state yet.

We had spent almost the entire night crawling cautiously over Strawberry Pass in Utah and lost a lot of time. Dean headed pell-mell for the mighty wall of Berthoud Pass that stood a hundred miles ahead on the roof of the world, a tremendous Gibralterian door shrouded in clouds. He took Berthoud pass like a June bug, same as Tehachipi, cutting off the motor and floating it, passing everybody and never halting the rhythmic advance that the mountains themselves intended, till we overlooked the great hot plain of Denver—and Dean was home.

I didn't float like a June bug. After a night in the DeVille in Winter Park, Colorado, I woke up to snow. The DeVille had traction control, ABS, and Stabilitrak, of course, but it didn't have winter tires or snow chains. While snowplows cleared the way on the westbound side of Highway 40, I crept along on the eastbound side. slipping sideways a couple times and getting into the ABS once but otherwise easing safely down onto the plain of Denver, which was definitely not hot, as Sal described it, but in the low 30s. (Kerouac did all his adventures in the summer.)

He described arriving in Denver on an earlier leg, one on which he had hitchhiked from New York to see all his "pals" in Denver.

“…there were smokestacks, smoke, rail yards, red-brick buildings, and the distant downtown graystone buildings, and here I was in Denver. He let me off at Larimer Street. I stumbled along with the most wicked grin of joy in the world, among the old bums and beat cowboys of Larimer Street.

Fifty years later there were no old bums on Larimer Street, and no beat cowboys, either. There was a big retail development called Writer's Square on Larimer but the guy in the management office said it was named after the developer, not any writer. The lady in the Denver Visitor's Information office said that Kerouac didn't hang out in Denver, but up in Boulder, but Kerouac described in detail Denver streets that are still there—Larimer, Colfax, Federal—and he described taking a walk on a street called Welton, which isn't on the map anymore, between 27th and 23rd. He said there was a softball game being played at 23rd and Welton. After a little cruising around, the Cadillac was parked at Coors Field, the stadium where the Colorado Rockies play, at 23rd and Wazee, which is close enough. Then it's time to head east again to the mad blowin' jazz of Chicago.

And Denver receded back of us like the city of salt, her smokes breaking up in the air and dissolving to our sight.

Ahead lay the rangelands of eastern Colorado and then the interminable plains of the Midwest. With Dean in the car, the flatlands weren't a problem for Kerouac.

In no time at all we were back on the main highway and that night I saw the entire state of Nebraska unroll before my eyes. A hundred and ten miles an hour straight through, an arrow road, sleeping towns, no traffic, and the Union Pacific streamliner falling behind us in the Moonlight. I wasn't frightened at all that night; it was perfectly legitimate to go 110 and talk and have the Nebraska towns—Ogallala, Gothenburg, Kearney, Grand Island, Columbus—unreel in dreamlike rapidity as we roared ahead and talked.

I had a tougher time, so tough that I stopped in North Platte, Nebraska, to buy a CB radio and a Charlie Parker tape to have something to listen to other than insane daytime radio talk shows. Kerouac stopped in North Platte, too, but for whiskey. He noticed, "There were immense Vistas of the Plains beyond every sad street." It was about here that the boys decided they really liked the Cadillac.

It was a magnificent car; it could hold the road like a boat holds on water. Gradual curves were its singing ease. "Ah, man, what a dreamboat," sighed Dean… "You and I, Sal, we'd dig the whole world with a car like this because man, the road must eventually lead to the whole world. Ain't nowhere else it can go—right? Oh, and are we going to cut around old Chi with this thing!"

Dean decided right there "to make extra special fast time" to Chicago. With no Dean, not even a Delaney, I couldn't do the same and had to stop for the night in frozen West Des Moines, lowa, at the nicest Motel 6 in the world, as ice formed thick on 1-80.

The next day flew by, for both Kerouac's journey and mine.

...the sun reddening, and sudden sights of lovely little tributary rivers flowing softly among the magic trees and greeneries of mid-American Illinois. It was beginning to look like the soft sweet East again; the great dry West was accomplished and done. The state of Illinois unfolded before my eyes in one vast movement that lasted a matter of hours as Dean balled straight across…

The Cadillac nosed into Chicago before sunset.

Great Chicago glowed red before our eyes. We were suddenly on Madison Street among hordes of hobos, some of them sprawled out on the street with their feet on the curb, hundreds of others milling in the doorways of saloons and alleys… Screeching trolleys, newsboys, gals cutting by, the smell of fried food and beer in the air, neons winking- "We're in the big town, Sal! Whooee!"

It was big. But there were no hordes of hobos sprawled out on Madison; the sidewalks were full of fashionable pedestrians running around like it was New York. I parked the DeVille on Madison Street because that's where Dean Moriarty parked his, and set out looking for Chicago jazz. Since my ATM card had stopped working in Salt Lake City, leaving me to live off credit cards and whatever "food" they sold in gas stations. I was down to $14 cash. The best jazz place I could find was called Andy's and there was a $10 cover. With four bucks left, I went in. It was the best $10 I ever spent. The Von Freeman Quintet could probably trace its roots back to Kerouac's time. Von Freeman himself led the band, playing a big, worn saxophone, swaying his head back and forth as if he could not believe the sad notes that were coming out.

He raised his horn and blew into it quietly and thoughtfully and elicited birdlike phrases and architectural Miles Davis logics. These were the children of the great bop innovators.

A lady sitting next to me named Frances Wharton said she was 73 years old. I figured she could very well have been hanging out here when Dean and Sal first came through. She called Freeman "a real gone cat" and I almost couldn't believe she actually said that. "You know how you listen to jazz?" she asked. "You got to feel it. You got to listen to the sax, you got to listen to the bass, you got to listen to the drums, you got to listen to the piano. You feel it in your toes and it moves up and you gotta feel it."

I stayed almost until the place closed then drove east again, watching the sunrise somewhere on 1-94 in western Michigan. Two days later I parked the car at the airport and flew home to Los Angeles. It had taken six days to go 2,960 miles east. It took five hours to go west. I flew over the storm I had just driven through, over the mad, flat plains with their little towns and circles of crops, over the Rockies and the deserts and finally back into Los Angeles, touching down "at the edge of the continent" Kerouac said.

And suddenly there was nowhere left to go.