RNC speakers come out against 'cancel culture,' unless Trump does the canceling

The Republican Party has apparently become the party of free speech, which is more than a little strange. The party is headed, after all, by a man who had peaceful protesters violently evicted from a public park so he could march to a church with a Bible. This is a president who responded to unflattering coverage in the Washington Post by forcing the Pentagon to literally cancel a contract with Amazon, because it is owned by Jeff Bezos, who also owns the Post. Yet for four straight days at the Republican National Convention, one speaker after another proclaimed the party’s passion for free speech and independent thinkers, and denounced “cancel culture.”

Donald Trump Jr. pronounced the Republican Party “the home of free speech.” Madison Cawthorn, a 25-year-old congressional candidate from North Carolina, spoke of the party’s commitment to “freedom of speech, not freedom from speech.” Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee accused “leftists” of trying to “cancel” police officers and soldiers. Nicholas Sandmann, a young man publicly accused of harassing a Native American activist, explained, “I learned what was happening to me had a name. It was called being canceled, as in annulled, as in revoked, as in made void.” President Trump observed, “The goal of cancel culture is to make decent Americans live in fear of being fired, expelled, shamed, humiliated and driven from society as we know it.”

This is the same president, by the way, who personally tried to “cancel” Goodyear tires because of a company policy discouraging employees from wearing political paraphernalia, including MAGA hats. “Don’t buy GOODYEAR Tires,” tweeted Trump. He also called for firing football players who refused to stand during the national anthem. “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners … say, Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, out. He’s fired. He’s fired!” ad-libbed the president during a rally.

Given his personal inclinations, it’s difficult to take this Trump party concern about speech and cancel culture seriously. For all the passionate testimonials to free speech and independent thought at the convention, the speakers voiced the same message, repeating, as if by rote, the identical received truth — which, best as I could tell, has something do with a radical Democratic plan to destroy America by sending prisoners and anarchists to pillage the suburbs. It seems unlikely their thoughts on speech would be any more enlightening or original, which is a shame, because Americans desperately need to grapple with the issue of how we talk to one another. In a moment when thousands of our countrymen are needlessly dying from an epidemic, when the streets are filled with anger over senseless killings and structural inequity, we need to find a way to cut through the noise and have a productive political dialogue. But instead of encouraging honest and thoughtful discourse, the president and his acolytes routinely add scaremongering and scapegoating to already explosive situations, occasionally inspiring troubled young men, sometimes with weapons, to take matters into their own hands.

In the old days, clearer thinking was assumed to be a natural product of copious free speech. And by the old days I don’t mean 1791, when the Bill of Rights was ratified. I mean the 1920s and 1930s, when America began to take free speech seriously.

For nearly its first 140 years of existence, we treated the First Amendment like some precious watch left to us by a revered grandfather; we would take it out periodically and admire it, and then forget about it for years at a time. It was not until after World War I, when America prosecuted thousands of critics of the war, that we began to question whether we should be imprisoning people simply for speaking out. That era gave birth to the ACLU and a free speech movement and spurred a lot of serious thinking about speech.

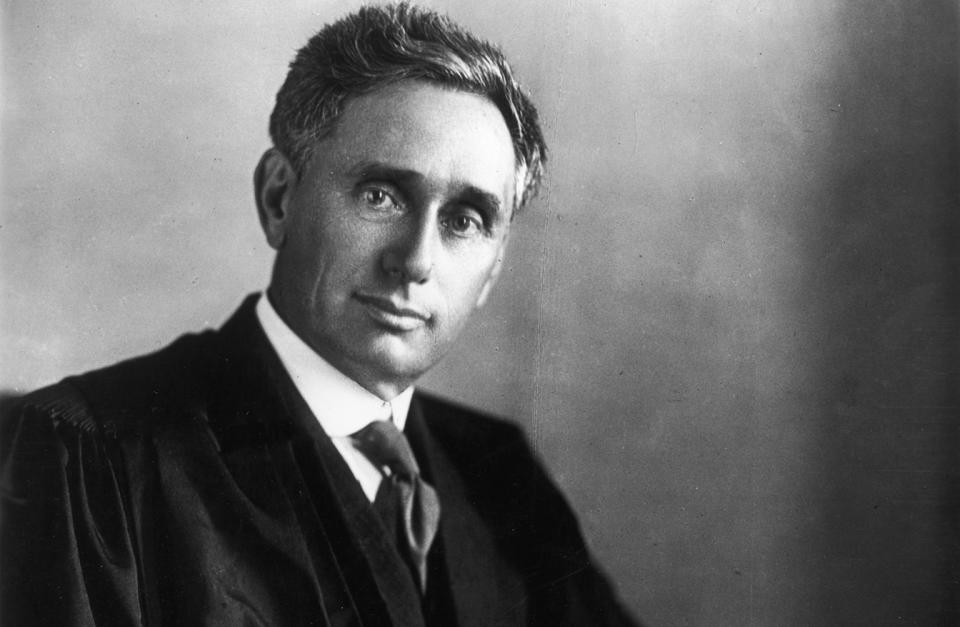

Whitney v. California, a 1927 case involving a California woman who had joined the Communist Party, inspired Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (joined by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.) to write an eloquent concurring opinion on free speech. “Those who won our independence believed … that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth,” wrote Brandeis, who believed that extensive dialogue offered “adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine.”

Brandeis was likely wrong on that point. Indeed, some think the First Amendment itself may prove inadequate to current challenges. In “The Perilous Public Square,” Columbia law professor Tim Wu wonders whether the First Amendment is obsolete. The pressing issue today, in his view, is not restriction of speech but overabundance of it. Much of that speech is misleading or dishonest, which, given audiences’ limited time and attention, allows it to crowd out more useful speech. It is a challenge, notes Wu, for which “First Amendment doctrine seems at best unprepared.”

As for cancel culture, that too is an important issue, though not necessarily in the way the RNC crowd talks about it. Some people may, in fact, deserve to be canceled — or criticized. Publicly calling someone’s ideas unfounded, or even stupid, is not necessarily equivalent to violating their First Amendment rights or “canceling” them. The more serious problem may not be the criticism, even contempt, that a few conservative speakers have suffered, but the evolution of criticism into harassment by unthinking online mobs who may be ill informed about the very offenses they are attacking. Michigan State University professor Anjana Susarla has written about the social media algorithms that make it easy to inflame online anger and target hapless victims. “One person tweeting her outrage would normally fall largely on deaf ears. But if that one person is able to attract enough initial engagement, algorithms will extend that individual’s reach by promoting it to like-minded individuals. A snowball effect occurs, creating a feedback loop that amplifies the outrage. Often, this outrage can lack context or be misleading, but that can work in its favor. In fact … misleading content on social media tends to lead to even more engagement than verified information,” writes Susarla.

No one should be canceled because a social media algorithm mislabels or misrepresents what they have said, written or done. No one should be subject to the online equivalent of a lynch mob. How to prevent that is an important issue to explore.

Then there is the matter of widespread ignorance around even the most basic issues concerning speech. A recent study by Everette Dennis and Klaus Schoenbach of Northwestern University found that 91 percent of Americans believe freedom of speech is “one of the values that makes America great,” and 89 percent believe in freedom of the press. Some 40 percent also see the press as the “enemy of the people,” and some 29 percent believe that Trump should shut down such outlets as CNN, the Washington Post and the New York Times. Those respondents presumably have no idea that the essential purpose of the First Amendment is to deny the government such power — which, at the very least, underscores the need for educators to do a better job of explaining what free speech means and entails.

Brandeis believed that speech was, in a sense, self-correcting, that good speech would inevitably drive out bad, that truth would eventually emerge from dialogue. We are learning that none of that is necessarily true, and that as essential as free speech is to our way of life, it can also be a threat — for which we must become better prepared.

Ellis Cose is the author of “Democracy, If We Can Keep It: The ACLU’s 100-Year Fight for Rights in America,” published in July, and “The Short Life and Curious Death of Free Speech in America,” coming Sept. 15. He is currently working on a history of America.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

You don't need the U.S. Postal Service to deliver your mail-in ballot

'I trusted them.' Some 'Build the Wall' donors feel cheated by Bannon. Some don't care.

Exclusive: DHS warns of fake election websites potentially tied to criminals, foreign actors

Oleandrin, touted as COVID-19 cure, has no scientific support