The rise of monkeypox

Once rarely seen outside of Africa, the disease is spreading across the U.S. and around the world. Here's everything you need to know:

What is monkeypox?

First identified by Danish scientists in 1958, monkeypox is caused by a virus that's a milder cousin of smallpox. It was discovered in laboratory monkeys, but its primary vectors are thought to be rodents. The first known human case surfaced in a 9-month-old boy in Congo in 1970. Since then, most cases have been limited to West and Central Africa, where people catch it by coming into close contact with infected animals. Limited cases traceable to African animals have occurred elsewhere, including the U.S., where in 2003 about 70 cases were reported among people who got it from pet prairie dogs who'd been housed with African animals. But the current outbreak is unprecedented.

Why have there been so many cases?

The disease is now spreading from human to human, overwhelmingly through men having sex with other men. Since the first cases surfaced in May, the spread has been rapid. About 35,000 cases have been confirmed worldwide, and 12,689 in the U.S. as of Aug. 16, according to the Centers for Disease Control — a 34 percent increase from a week earlier. Those numbers are thought to be a fraction of the true case counts. The World Health Organization declared monkeypox a global emergency on July 23; the U.S. designated it a national health emergency two weeks later.

How does it affect people?

Those infected typically develop a flu-like illness, with symptoms including fever, head and muscle aches, fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes. That's followed by a painful rash that develops into fluid-containing pustules that scab over. Symptoms generally appear six to 13 days after exposure, though it can take as long as three weeks. Patients are infectious from when symptoms start to when the scabs fall off (sometimes leaving scars). There have been no fatalities in the U.S., and patients typically recover on their own. But the pain and discomfort can be debilitating; one study found it led to hospitalization in 10 percent of patients. "It was like someone taking a hole puncher all over my body," said Kevin Kwong, a California man hospitalized with over 600 lesions.

Why is it spreading now?

Virologists think monkeypox may have undergone small mutations that have enabled it to pass readily from person to person. It spreads primarily through intimate, skin-to-skin contact, and possibly through genital fluids, with 98 percent of cases affecting gay or bisexual men, according to a recent study. In theory, it may also spread through respiratory droplets from a cough or sneeze or through bedding or towels shared with an infected person — but scientists are quick to note that it's not nearly as infectious as Covid, which spreads easily through the air. "What we're not seeing is casual spread," said Jay Gladstein, an infectious-disease specialist in Los Angeles. "It's got to be really close contact."

What's been the response?

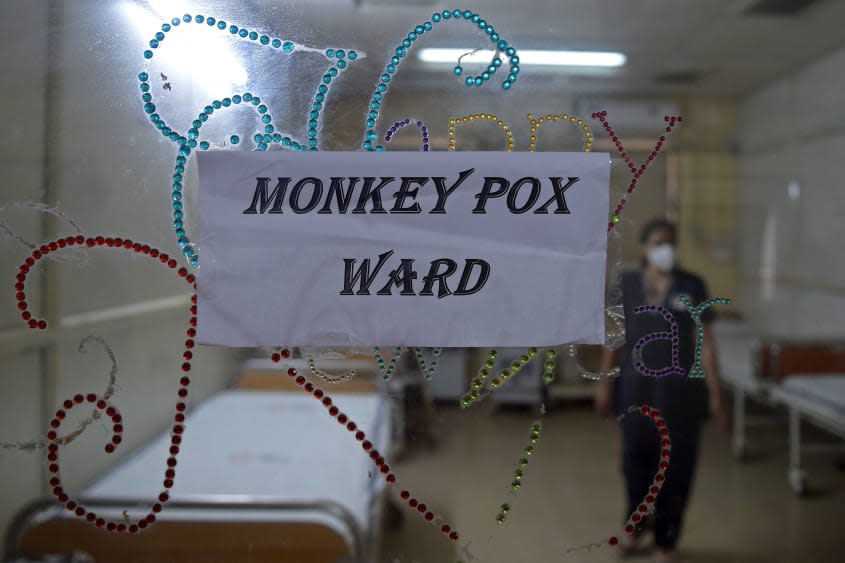

Scientists say federal health officials were too slow to react when the first cases surfaced outside Africa in early May. Community spread "should have rung alarm bells," said Perry Halkitis, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health. That was when officials should have begun ramping up testing capacity and stockpiling vaccines. Instead, early testing was limited and results had to be sent to the CDC for confirmation; it wasn't until late June that the government expanded capacity by sending tests to commercial labs. The government holds a large stockpile of an effective vaccine — Jynneos, which was formulated for smallpox — but was slow to release doses and to order more. While millions of doses are now on order, men in some cities are lining up for a very inadequate number of shots, and the FDA has authorized doctors to split up doses to extend them. Critics say contact tracing has been inadequate, and so has outreach to doctors, who may not realize their patients have monkeypox. The critics also say public health messaging has failed to clearly warn gay and bisexual men that they are by far at the highest risk of being infected. [See box.]

Can it be contained?

That remains to be seen, but many experts say it's too late to reverse the outbreak. Monkeypox is destined to become "entrenched" in the population, they believe, and while it won't spread as widely as Covid has, it may make inroads into the general population. At least five children and one pregnant woman in the U.S. have been infected, through contact with infected men. One concern is that the virus could take root among domestic animals, which could spread it back to humans. Improved contact tracing, better outreach campaigns, and expanded funding of sexual health clinics can all help combat the virus, but experts say an aggressive, large-scale response is needed now. "There is an imminent window of time by which we can get ahead" of the spread, said Tyler TerMeer of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. "And that window continues to close."

The shadow of AIDS

Should monkeypox be spoken of as primarily a sexually transmitted disease? That's become a thorny subject, and has sparked debate over how awareness efforts should be targeted. Technically, anyone who has skin-to-skin contact with an infected person could get monkeypox. Some health officials believe it's important to stress that point and not label monkeypox a "gay disease." People might think, "I'm not a gay man, so I'm good no matter what," said Stella Safo, founder of Just Equity for Health. But others say public health officials afraid of stigmatizing gay men have been too timid about emphasizing that they're almost exclusively the ones getting infected. "Pretending that that's not the case doesn't help any of us," said Will Nutland, founder of two British health groups for gay and bisexual men. Looming over the conversation is the legacy of the early years of AIDS, when talk of a "gay plague" brought a stigma that still resonates. How to speak about — and effectively combat — this new disease is "a fine line that many people are walking right now," said Perry Halkitis of the Rutgers School of Public Health.

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

You may also like

5 cartoons about Trump's rage over the Mar-a-Lago raid

Trump calls McConnell a 'broken down hack' over complaints about 'candidate quality' in Senate races

7 scathingly funny cartoons about Giuliani's Georgia testimony